Astronomers have been dazzled by the sheer number of planets there seem to be in the galaxy. According to a recent estimate, there’s on average at least one planet orbiting every star, which comes out to around 400 billion exoplanets in the Milky Way as a whole. This is probably a conservative number, and it doesn’t take into account the vast number of “rogue planets” which are probably wandering free without any home star.

On top of this is the variety. Planets have been found around Sun-like stars, red dwarfs (the smallest kind of star), and some orange giants. They’ve been found in systems where there are two or more stars. And they’ve been found right on our cosmic doorstep. The nearest known exoplanet accompanies Alpha Centauri B, one of the stars in the Alpha Centauri system, just over 4 light-years away.

The exoplanets themselves cover a spectacular range of types and orbits. The majority discovered to date are gas giants, like Jupiter or Saturn, but this is simply a selection effect, because big, heavy planets, especially those in small orbits, cause more noticeable wobbles in the motion of their central stars, and so give themselves away more easily.

As time goes on, and their instruments and search techniques become more sensitive, astronomers are finding a higher proportion of small, rocky planets, like those in the inner part of the solar system. Some of these new-found rocky worlds are even smaller than the Earth; the smallest known, called Kepler-37b, is only slightly bigger and more massive than the Moon.

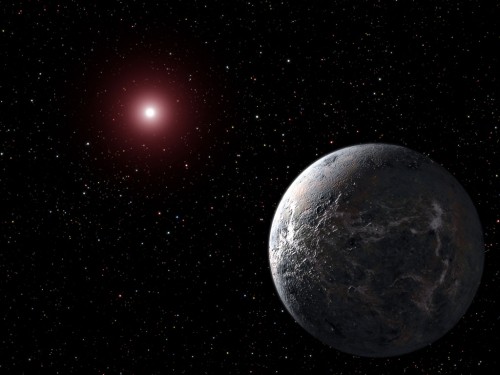

The big question on everyone’s mind is: when will we find another Earth—a planet similar in size to our own that orbits within the “habitable zone” of its star? Roughly speaking, the habitable zone is the region around a star in which a planet has to move to be able to have liquid water permanently on its surface. Some planets have already been discovered moving in such an orbit, and it’s only a matter of time before one of these turns up that’s almost identical in size and mass to the Earth. But for life to exist on a planet, it may not be necessary that its star is a twin of the Sun or that the planet be exactly Earth-like. Observations made by NASA’s Kepler space telescope have shown that about 15 percent of red dwarfs have planets between 0.5 and 1.4 times the size of Earth orbiting in their habitable zones. Based on that estimate the nearest habitable exoplanet may be less 7 light-years away.

Scientists are also making progress in analyzing the make up of the atmospheres of exoplanets. This is crucial in the search for extraterrestrial life, because certain gases and combinations of gases would be strong indicators of biological activity on the surface. The first step is to isolate the reflected light coming from the planet from the vastly brighter glare of the central star. Having done this, the trickle of light from the planet can be passed through a spectroscope to see at what wavelengths it has been absorbed by gases in the atmosphere. More powerful telescopes in the future, both on the ground and in space, will make this possible for large numbers of exoplanets.