Friday is almost universally recognized as an indicator that the weekend draws inexorably closer … but for NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, today will mark a milestone as its primary target, the dwarf world (and ex-planet) Pluto, draws ever closer. Scheduled to reach Pluto and its mysterious system of moons in mid-July 2015, New Horizons is now just 5 Astronomical Units (AU)—about 464.8 million miles (747.9 million km)—from becoming the first machine fashioned by human hands ever to gain a close-up glimpse of one of the Solar System’s hidden gems. “This Friday, we’ll be just 5 AU from Pluto,” exulted New Horizons’ Twitter page to its 43,000 followers, “and closing.”

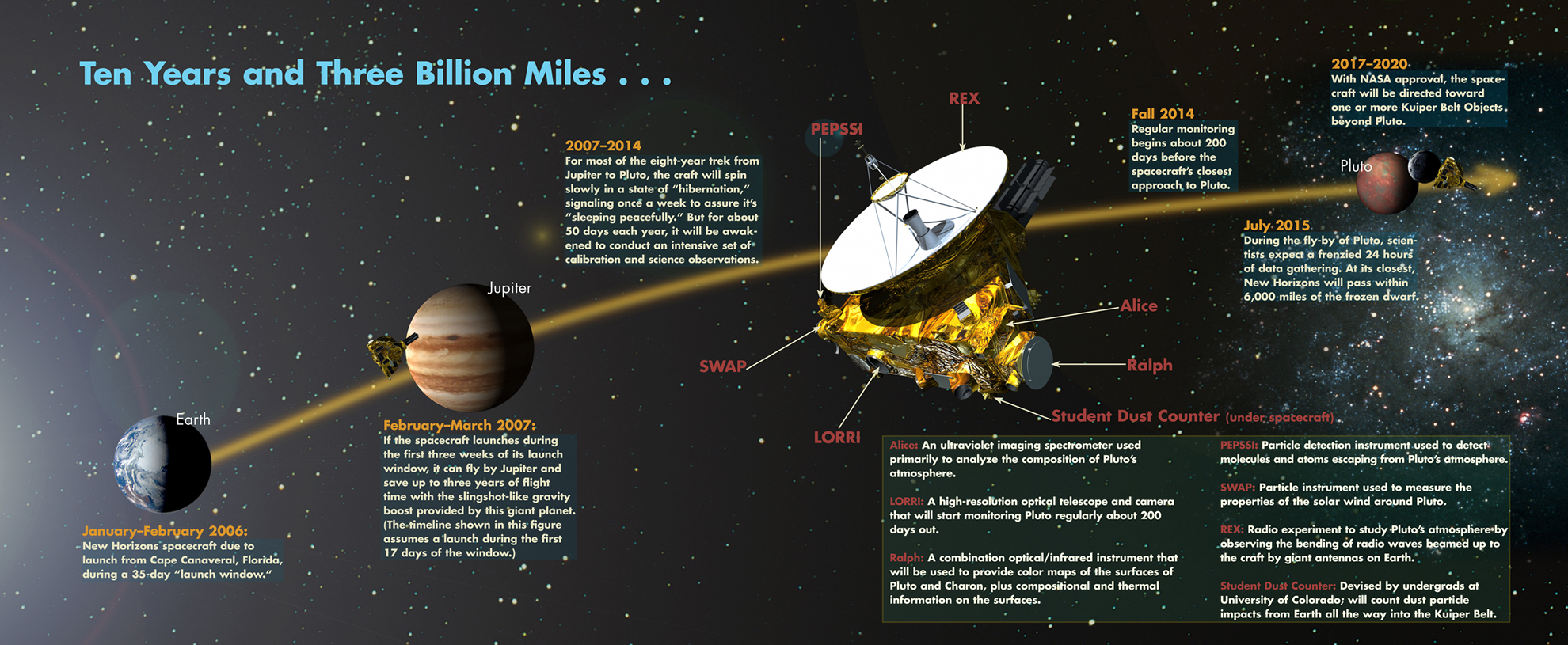

Launched atop an Atlas V booster from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., back in January 2006, it has been quite a journey for New Horizons … and a journey which might never have happened. An earlier mission, the Pluto Kuiper Express, had already been cancelled, due to budgetary concerns, and New Horizons was ultimately selected by NASA in June 2001. Four years later, its assembly was completed and the spacecraft was delivered to the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., for final testing. New Horizons moved to Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in September and was transported to Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 in December for installation atop the Atlas V. Although the “launch window” to reach Pluto opened on 11 January 2006, the spacecraft and its team endured no fewer than two postponements before thundering aloft on 19 January.

New Horizons was inserted directly onto an Earth-and-solar-escape trajectory, departing the Home Planet at a relative velocity of 36,373 mph (58,536 km/h). This set a new record for the fastest human-made object ever to leave Earth, and the spacecraft passed Mars in early April 2006, followed by Asteroid 132524 APL—named by New Horizons’ Principal Investigator in honor of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, which runs the mission—in June and gained its first sighting of Pluto, from a distance of 2.6 billion miles (4.2 billion km), the following September. Passing Jupiter in February 2007, followed by the orbit of Saturn in June 2008 and the orbit of Uranus in March 2011, New Horizons’ journey into the unknown steadily resolved Pluto for the first time as something more than a distant speck of light. By December 2011, it had drawn closer to the dwarf world than any other human spacecraft, eclipsing the previous record-holder, Voyager 1, which flew past Pluto at 10.58 AU in May 1988.

Earlier this year, New Horizons’ Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) acquired its first image of Pluto’s large moon, Charon, from a distance of almost 550 million miles (885 million km), which resolved it as a dim companion object. Next summer, the spacecraft will pass beyond Neptune’s orbit and in February 2015 will begin its first long-distance observations of Pluto. By May, its resolution will eclipse that of the Hubble Space Telescope, and on 14 July it will hurtle past Pluto at a distance of about 8,510 miles (13,695 km), taking in glimpses of Charon and the other moons, Hydra, Nix, Kerberos, and Styx. The remainder of New Horizons’ mission—which is expected to continue until at least 2026—will be spent performing flybys of mysterious Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) and may be in a position to conduct explorations of the Sun’s outer heliosphere if still functional in 2038.

Having traversed a distance of 26.38 AU, or about 2.4 billion miles (3.9 billion km) from Earth, in less than eight years, New Horizons’ journey thus far has been nothing short of phenomenal. Round-trip communications times between the spacecraft and Earth now stand at about 7.3 hours, and it is fitting that in addition to its payload of scientific instruments it carries some of the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh (1906-1997)—the astronomer who discovered Pluto in February 1930—and a dust counter named in honor of Venetia Burney (1918-2009), who as a schoolgirl suggested the name “Pluto” for the newly found world.

In addition to intrinsic scientific interest, the need to send a mission to Pluto came about because of its unusual elliptical orbit around the Sun, which brings it as close as 30 AU (2.8 billion miles or 4.5 billion km) and as far as 50 AU (4.6 billion miles or 7.5 billion km), and this broad difference in solar distance is thought to cause profound changes to its tenuous atmosphere. As Pluto moves farther from the Sun, this atmosphere is believed to sublimate as frost onto its surface, and reaching the icy world before this occurred was considered imperative for maximum scientific yield.

Even the best-resolution images, acquired by the Hubble Space Telescope, have revealed little more than a few bright and dark blotches on the Plutonian surface, and it has been suggested that it is a similar world to Neptune’s moon Triton in physical nature. Yet if these bright and dark features are visible from Hubble’s immense distance, they are clearly significant and planetary geologists expect Pluto to reveal evidence of a complex evolutionary history. Its thin atmosphere was first identified in 1988, boasting a pressure at the surface about 100,000 times smaller than on Earth, but nevertheless sufficient to support meager weather systems, winds, particulate haze, and maybe even an ionosphere. Pluto’s gravity is so weak that whatever atmosphere it does possess is probably not very close to the surface. As for Charon and the other moons, they pose little more than a blank slate at present, awaiting New Horizons to discover and write their stories.

Discovered by James Christy of the U.S. Naval Observatory in 1978, Charon comprises essentially water-ice, whereas Pluto is predominantly coated with nitrogen frost, together with some methane and carbon monoxide ices. Both have densities about twice that of water, which is suggestive of bodies which are roughly two-thirds rock and one-third water-ice. The distance between Pluto and Charon is relatively small—only about 12,180 miles (19,600 km), or about 19 times closer than the distance between Earth and the Moon—and both are tidally locked, presenting the same face to each other. To an observer on the Plutonian surface, Charon would thus hang, in perpetuity, never rising or setting, in the dark sky.

The sky-falling notion that Pluto’s atmosphere might freeze and collapse appears not to be entirely accurate. Writing last month for The Planetary Society, Emily Lakdawalla noted that astronomers have monitored its progress on numerous occasions during the past 25 years. “Throughout the 2000s, the atmosphere seemed to be at a plateau,” Lakdawalla wrote. “There was some variation in its pressure, but the error bars all overlapped, so it was hard to say which way it was going.” Three scenarios existed to explain Pluto’s atmospheric behavior, two of which predicted an atmospheric collapse by now, whilst recent “occultations” of the dwarf planet suggested that it was actually thickening, even as it moved farther from the Sun. “Plugging these data points back into their climate models,” Lakdawalla continued, “the only model that can explain the observed behavior of the atmosphere is one in which there is a permanent north polar cap. And in those models, the atmosphere never completely collapses. It waxes and it wanes, but it never collapses.”

Approximately 70 days before closest approach, New Horizons’ imaging gear will set to work mapping and taking daily spectral measurements of the Plutonian surface. These will be used to better understand the chemical and mineralogical composition and surface temperature of both Pluto and Charon. Although the spacecraft’s long voyage will be rewarded by a matter of weeks to complete the bulk of its scientific work, the excitement of the New Horizons team to get to work is palpable. Pluto has long since been relegated from its original definition of planet and is now controversially described as a dwarf planet, although several members of the New Horizons team still defy the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and continue to regard it as The Ninth Planet.

Today, as workers leave work for the weekend and head home, New Horizons will pass another milestone as it heads to Pluto. The countdown clock is ticking. Less than 630 days—or 90 weeks—from now, the spacecraft will grab for itself a ringside seat for humanity’s first-ever up-close glimpse of Pluto. And if previous planetary encounters are anything to go by, all bets are off. We can be certain of only one thing: that Pluto will be a world of surprises.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

I wonder what Clyde Tombaugh would think about the mission?

I think he would have been elated!