“Threading the needle” through exceptionally ugly weather, and coming close to a scrub and 24-hour turnaround, United Launch Alliance (ULA) has successfully delivered its 11th mission of 2014 into orbit. Liftoff of the Atlas V—which flew in its “401” configuration, numerically designated to describe a 13-foot-diameter (4-meter) payload fairing, no strap-on boosters, and a single-engine Centaur upper stage—took place at 8:10 p.m. EDT Tuesday, 16 September, from the storied Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla. The launch occurred at the very last moment of a 146-minute “window,” which extended from 5:44 p.m. until 8:10 p.m. and, like July’s AFSPC-4 campaign, ran down to the wire until the final minutes.

As described in AmericaSpace’s preview article, the primary payload for the mission was the classified CLIO satellite, developed by Lockheed Martin Space Systems “Skunk Works” on behalf of an unnamed U.S. Government Agency, and for an unknown purpose. However, the satellite’s heritage was known and it was announced before the flight that it was based upon commercial technology, specifically Lockheed Martin’s proven and capable A2100 “bus,” which first flew in September 1996. This bus has supported dozens of payloads over the past two decades, primarily commercial telecommunications satellites for various nations, but also military and technology missions, including the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) and Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) networks and members of the Geostationary element of the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS).

Tuesday’s launch of CLIO also represented the 25th flight of the Atlas V 401 and ULA’s 60th overall mission from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. The 196-foot-tall (60-meter), pencil-like rocket began its short, 1,200-foot (370-meter) rollout from the Vertical Integration Facility (VIF) at 10:30 a.m. EDT Monday, 15 September, and was “hard-down” on the SLC-41 pad surface by 11:00 a.m. In addition to standard electrical, fluid, and mechanical interface verifications, one of the Atlas V’s propellants—a highly refined form of rocket-grade kerosene, known as “RP-1”—was loaded aboard the vehicle on Monday afternoon.

Weather conditions for an on-time Tuesday evening launch were hardly optimum. The 45th Space Wing had already forecasted only a 40 percent likelihood of acceptable conditions at T-0. “Strengthening mid-level winds will cause late-afternoon thunderstorms over the interior to drift back toward the East Coast,” it was stressed on Monday evening. “Likewise, upper-levels winds with a westerly component will transport anvil clouds back toward the East Coast. Thunderstorms will begin dissipating by early evening.” At the same time, sunspot activity threatened high-risk X-class solar flares and an elevated proton flux throughout Tuesday’s launch window. Summing, the 45th Space Wing noted that the primary concerns were anvil clouds, thick clouds, and the potentially elevated proton flux level.

Nonetheless, efforts to launch CLIO on Tuesday entered high gear, and by 11:30 a.m. EDT the countdown got underway, with flight control systems powered up, and ULA engineers pressed smoothly into ground command control and communications testing. This 3.5-hour process involved the initiation and verification of proper communications between the Atlas V and the Launch Control Center, as well as the status of the critical Flight Termination System (FTS), tasked with destroying the vehicle in the event of a major accident during ascent.

Fueling of the Atlas V with liquid oxygen and hydrogen was preceded by a standard protocol to “chill-down” the propellant lines, in order to avoid thermally shocking and fracturing them, as well as purging with gaseous nitrogen to remove potentially harmful contaminants. By 3:45 p.m. EDT, all flight control and communications tests had been satisfactorily concluded and the Launch Director gave formal authorization to begin loading the cryogens aboard the Atlas. Closed-loop testing of the rocket’s automated systems and on-board sensors was completed shortly after 4 p.m., although weather conditions over the Cape turned steadily uglier. Approximately one hour before the 5:44 p.m. opening of the launch window, the propellant tanks of the Atlas V’s first stage were full and liquid oxygen tanking transitioned to a “topping” mode, undergoing continuous replenishment until close to launch time.

That launch time, however, seemed elusive. By 5:15 p.m., less than 30 minutes before the opening of the window, a storm passed through Cape Canaveral, but although lightning strikes had been recorded close to the southern end of the Cape, the SLC-41 area itself missed the associated rain. Conditions worsened, however, and within a matter of minutes the storm began rolling in over the launch pad, triggering a “Phase II” lightning alert. “A Phase II warning will be issued when lightning is imminent or occurring within 5 miles (8 km) of the designated site,” it was explained by the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Public Affairs Office (PAO). “All lightning-sensitive operations are terminated until the Phase II Warning is lifted.” The Phase II Warning follows upon the less-severe Phase I, in which an advisory is issued for lightning forecasted to strike within 30 minutes, in order to give “personnel in unprotected areas time to get to protective shelter” and provide “personnel working on lightning-sensitive tasks time to secure operations in a safe and orderly manner.”

With a Phase II alert in place, weather was declared “Red” (“No Go”), and shortly after 5:30 p.m. the countdown entered what was expected to be a lengthy built-in hold at T-4 minutes. Multiple violations of Launch Commit Criteria (LCC) made it obvious that the clock would not resume counting at 5:40 p.m., as it would be required to do in order to achieve a liftoff at the 5:44 p.m. opening of the window. A few minutes later, a revised T-0 time of 5:49 p.m. was established, although the weather remained “Red” and shortly thereafter it was announced that a launch would not occur before 6:45 p.m.

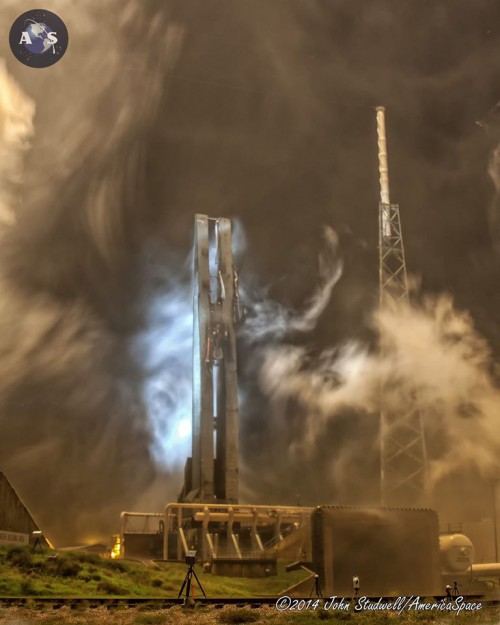

Steadily, conditions began to improve, as the area immediately surrounding SLC-41 cleared, but ominous, iron-gray clouds continued to dominate the Cape skyline. The T-0 time was shifted slightly to No Earlier Than 6:44 p.m., but with several LCC violations still in force, it was apparent that the weather would likely remain “Red” until 7:45 p.m. During this period, clouds and rain wholly enshrouded the launch pad, obscuring it from the press site, although it was hoped that the Atlas V might “thread the needle” and achieve a successful launch as soon as 7:28 p.m. That time quickly became untenable, as did a second extension to 7:33 p.m. and a third, to 7:43 p.m. Tuesday’s 146-minute window was due to close at 8:10 p.m., requiring the count to pick up from the T-4-minute hold point at no later than 8:06 p.m., in order to ensure that all of the Terminal Countdown milestones were conducted.

Finally, at 7:37 p.m. the ULA launch team conducted its final Go-No Go poll and returned a unanimous “Go for Launch,” pending a final “Green” (“Go”) report from the weather officer at T-60 seconds. The Launch Director authorized the clock to be released at 7:40 p.m., tracking a liftoff at 7:44 p.m. As the opening seconds of the Terminal Countdown passed, the Atlas V Common Core Booster (CCB) propellant tanks reached flight levels and flight pressure and the fill-and-drain valves were closed for flight. Then, at 7:42 p.m., with weather conditions anticipated to remain “Red” for at least another quarter-hour, another hold was called. In what appeared to be an unpleasant repeat of July’s AFSPC-4 launch campaign, a new T-0 was established at 8:10 p.m.

This, of course, was right at the very end of Tuesday’s launch window, making it increasingly likely that unless the gods of the weather suddenly changed direction a 24-hour scrub would be inevitable. By 8:00 p.m., the weather had gone to “Green,” and at 8:04 p.m. the final Go-No Go poll of all stations returned its second “Go for Launch” of the evening. With the Terminal Countdown back in effect, the Atlas V’s autosequencer assumed primary command of all vehicle critical functions through liftoff. Liquid oxygen replenishment concluded, the fuel and oxidizer valves were again closed for flight, and the propellant tanks were verified at their proper flight pressures.

At T-5 seconds (8:09:55 p.m.), sound-suppressing water flooded across the SLC-41 pad surface and into the flame trench, in order to minimize reflected energy and acoustic waves at the instant of liftoff. The ignition sequence of the Atlas V’s single, Russian-built RD-180 engine commenced at T-2.7 seconds (8:09:57 p.m.), punching out 860,000 pounds (390,000 kg) of thrust, and the vehicle was committed to flight at 8:10:00 p.m. EDT, right at the end of the window. The rocket, whose thrust-to-weight ratio is only 1:16, lumbered off the pad at T+1.1 seconds and climbed vertically for the first 16 seconds of the mission. At this stage, the Centaur avionics commanded a pitch, roll, and yaw program maneuver to actively guide the stack onto the proper flight azimuth to insert CLIO into orbit.

Passing through the sound barrier and through a region of maximum aerodynamic turbulence (colloquially known as “Max Q”), about 80 seconds into the flight, the RD-180 continued to burn hot and hard for more than four minutes in total. It shut down at 8:14:05 p.m. and separated from the rapidly climbing stack a few seconds later. The 41-foot-long (12.4-meter) Centaur and CLIO were now on their own to execute a pair of discrete “burns” to deliver the payload into its correct orbit. The first burn of the Centaur’s 22,300-pound-thrust (10,100-kg) RL-10A liquid oxygen/hydrogen engine got underway at T+4 minutes and 17 seconds and lasted for 13.5 minutes, during which time the two-piece (or “bisector”) Payload Fairing (PLF) at jettisoned. This exposed the top-secret CLIO satellite to the hostile space environment for the first time.

Main Engine Cutoff-1 (MECO-1) took place precisely on time, at 8:27:58 p.m., after which the Centaur/CLIO combo “coasted” for more than two hours, ahead of the second RL-10A burn at 10:57:52 p.m. Unlike its predecessor, this burn was brief, lasting barely 70 seconds, and the engine fell silent for the second time high above the Indian Ocean, to the west of Australia. Following MECO-2, the CLIO spacecraft separated from the vehicle at 11:01:52 p.m., some two hours, 51 minutes, and 52 seconds after leaving Cape Canaveral.

“The burn duration suggests that the mission is targeting an elliptical transfer orbit, with an estimated inclination of about 25 degrees,” noted Spaceflight101. “The CLIO launch profile suggests either a Medium Earth Orbit insertion or an injection into a Geostationary Transfer Orbit with increased perigee.” However, it will be difficult to infer CLIO’s purpose—whether for geostationary military communications or a wholly different goal—until the orbit of the satellite is precisely tracked.

Tuesday’s launch of CLIO was the fifth to originate from the Cape’s SLC-41 in 2014, following hard on the heels of NASA’s latest Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-M) in January, the National Reconnaissance Office’s classified NROL-67 and NROL-33 missions in April and May, respectively, and last month’s launch of the most recent Global Positioning System (GPS) Block IIF spacecraft. Only one more Atlas V is due to fly from SLC-41 this year, with a 401 slated to deliver the GPS IIF-8 mission into orbit on 29 October. This final mission of 2014 will also mark the 50th total flight by a member of the Atlas V family.

BELOW: Photos from our coverage of the ULA Atlas-V CLIO launch. All photos credit Mike Killian, John Studwell and Alan Walters for AmericaSpace, all rights reserved, unauthorized use is prohibited.

– Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » CLIO »