The search for, and discovery of, exoplanets orbiting other stars has become a full-fledged endeavour in recent years, with thousands found so far and more being discovered practically every week. Now, NASA wants to take it a big step further by establishing a coalition of research groups and disciplines tasked specifically with this purpose.

Instead of being primarily the domain of astronomers, the new Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) will bring together many different experts in a variety of scientific fields to assist in the search for and classification of exoplanets, in particular ones which might be capable of supporting life of some kind.

“This interdisciplinary endeavor connects top research teams and provides a synthesized approach in the search for planets with the greatest potential for signs of life,” said Jim Green, NASA’s Director of Planetary Science. “The hunt for exoplanets is not only a priority for astronomers, it’s of keen interest to planetary and climate scientists as well.”

Supporting this effort will be the collective expertise from each of the science communities supported by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate:

- Earth scientists develop a systems science approach by studying our home planet.

- Planetary scientists apply systems science to a wide variety of worlds within our Solar System.

- Heliophysicists add another layer to this systems science approach, looking in detail at how the Sun interacts with orbiting planets.

- Astrophysicists provide data on the exoplanets and host stars for the application of this systems science framework.

The idea is to better understand how biology interacts with the atmosphere, geology, oceans, and interior of a planet and how these interactions are affected by the host star.

The first exoplanet orbiting a star similar to our Sun was found in 1995, although three others were found orbiting a pulsar, or collapsed dead neutron star, in 1992. According to the Open Exoplanet Catalogue, there are currently 1,912 confirmed exoplanets, with another 4,023 candidates discovered by the Kepler Space Telescope alone (both the main Kepler mission and the K2 extended mission). The Habitable Exoplanets Catalog now lists 30 known potentially habitable exoplanets.

The coalition will be an unprecedented collaboration in the search for extraterrestrial life outside of our own Solar System. According to Dr. Paul Hertz, Director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA:

“NExSS scientists will not only apply a systems science approach to existing exoplanet data, their work will provide a foundation for interpreting observations of exoplanets from future exoplanet missions such as TESS, JWST, and WFIRST.”

The project will be led by Natalie Batalha of NASA’s Ames Research Center, Dawn Gelino with the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExScI), and Anthony del Genio of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. There will also be team members from 10 different universities and two research institutes contributing. The teams were selected from proposals submitted across NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Following is a brief outline of the various teams involved and what they will be doing:

The Berkeley/Stanford University team is led by James Graham. They will focus on the question, “What are the properties of exoplanetary systems, particularly as they relate to their formation, evolution, and potential to harbor life?”

The “Earths in Other Solar Systems” team is lead by Daniel Apai from the University of Arizona. They will combine astronomical observations of exoplanets and forming planetary systems with powerful computer simulations and cutting-edge microscopic studies of meteorites from the early Solar System to understand how Earth-like planets form and how biocritical ingredients—C, H, N, O-containing molecules—are delivered to these worlds.

The Arizona State University team, led by Steven Desch, will look at planetary habitability within a chemical context. They will produce a “periodic table of planets” as well as assist other teams looking at the atmospheres of exoplanets.

The “Living, Breathing Planet“ team, led by William B. Moore, will study how the loss of hydrogen and other atmospheric compounds to space has changed the chemistry and surface conditions of planets in our own Solar System and beyond, to help determine the past and present habitability of Mars and Venus, forming the basis for identifying habitable and eventually living planets around other stars.

The team at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, led by Tony Del Genio, will examine habitability on a local scale, probing the habitability of rocky planets through time, to assist with the detection and characterization of habitable exoplanets in the future.

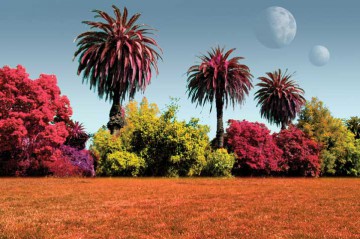

Image Credit: NASA/Caltech/Doug Cummings

The team at the NASA Astrobiology Institute’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory, led by Dr. Victoria Meadows, will combine expertise from Earth observations, Earth system science, planetary science, and astronomy to examine conditions which could affect the habitability of exoplanets, as well as the remote detectability of global signs of habitability and life.

The team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, led by Neal Turner, will explore why so many exoplanets orbit close to their stars, as well as investigate how the gas and dust close to young stars interact with planets, using computer modeling to go beyond what can be imaged with today’s telescopes on the ground and in space.

The team at the University of Wyoming, led by Hannah Jang-Condell, will explore the evolution of planet formation, modeling disks around young stars which are in the process of forming planets, notably “transitional” disks, which are protostellar disks that appear to have inner holes or regions partially cleared of gas and dust which may be caused by planets.

The Penn State University team, led by Eric Ford, will attempt to better understand planetary formation by investigating the bulk properties of small transiting planets and the implications for their formation.

Another Penn State team, led by Jason Wright, will study the atmospheres of transiting hot Jupiter planets with a high-precision technique called diffuser-assisted photometry, which will enable detailed characterization of the temperatures, pressures, composition, and variability of exoplanet atmospheres.

The University of Maryland and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center team, led by Wade Henning, will study tidal dynamics and orbital evolution of terrestrial class exoplanets. This will be to explore how intense tidal heating, such as the temporary creation of magma oceans, could help save Earth-sized planets from being ejected during the orbital chaos of early Solar System formation.

Another University of Maryland team, led by Drake Deming, will leverage a statistical analysis of Kepler data to extract the maximum amount of information concerning the atmospheres of Kepler’s planets.

The team led by Hiroshi Imanaka from the SETI Institute will conduct laboratory investigations of plausible photochemical haze particles in hot exoplanetary atmospheres.

The Yale University team, led by Debra Fischer, will design new spectrometers which will have the stability and precision needed to find Earth-like exoplanets orbiting nearby stars. It will also make improvements to the Planet Hunters website, which allows citizen scientists to search for transiting planets in the NASA Kepler public archive data.

The team led by Adam Jensen at the University of Nebraska-Kearney will examine the existence and evolution of exospheres around exoplanets, which are the outer, “unbound” portion of a planet’s atmosphere. This team had already previously made the first visible light detection of hydrogen absorption from an exoplanet’s exosphere, which indicated a source of hot, excited hydrogen around the planet. Such hydrogen could potentially provide clues about the long-term evolution of a planet’s atmosphere, including the effects and interactions of stellar winds and planetary magnetic fields.

The University of California, Santa Cruz team, led by Jonathan Fortney, will investigate how novel statistical methods can be used to extract information from light which is emitted and reflected by planetary atmospheres, which will help astronomers understand their atmospheric temperatures and the abundance of molecules.

The formation of such a coalition is a welcome and needed development in the field of exoplanet studies. Not so long ago it wasn’t known if any other planets existed outside of our Solar System. Now we know that our galaxy and the Universe are brimming with them. New space and ground-based telescopes being designed and built now will add many new exoplanets to the thousands which have already been discovered. With billions of such worlds now estimated to exist in our galaxy alone, NExSS will now help to usher in a time of unprecedented exploration and discovery.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

It is interesting to me that NASA panders to what the public craves in the way of brain candy but is not providing anything healthy. In my view Gerard K. O’Neill should be the guiding light of Human Space Flight. The NewSpace agenda is pushing living on Mars and LEO development- concepts that are obvious dead ends- while O’Neill’s vision of space colonization is being ignored. Why? Not hard to figure out.

O’Neill considered a massive state sponsored public works project utilizing lunar resources to be the prerequisite of any human presence in space. Exactly the opposite of the flexible path. The chances of finding a planet where humans can live on is exceedingly small compared to finding systems with asteroid and comet belts that can support space habitats.

So I think the children playing beneath the alien sky is….poor marketing.

The most important research in this area is not finding these worlds (or systems with asteroid and comet resources for space colonies)- that can wait.

The most important research is how to get to them. We already know how to build starships- Freeman Dyson figured that out half a century ago- we don’t know how to freeze people for the centuries it takes to travel to other stars.

But since being able to freeze and revive people is the ultimate disruptive technology and would turn the world upside down, don’t count on NASA having anything to say about it. They won’t talk about nuclear propulsion so they sure won’t say anything about cryopreservation.

Considering we are many decades if not centuries away from practical manned star travel, the motivation for today’s astronomers (or indeed, for astronomers for decades to come) is not to find extrasolar planets to travel to or colonize. And given that we have yet to begin to exploit the natural resources in our own solar system beyond the Earth, their motivation is not to detect exploitable extrasolar resources, either. Instead, their motivation is the same as their motivation for studying the worlds in our own solar system for over half a century: comparative planetology. It is by studying a wide variety of other planets that scientists are able to learn more about how planets in general “work” and place what they learn about the Earth into a wider context giving a deeper understanding of the inner workings of our world in the process.

We are currently in a position to develop the technology to learn a lot more about extrasolar planets in general and potentially habitable planets in particular long before we will ever have the technology to reach them. But that being said, learning more about these worlds and developing the technology to reach them are not mutually exclusive activities – posing this as an “either or” proposition is classic example of a false choice. Both areas can and should be pursued.

“Considering we are many decades if not centuries away from practical manned star travel-”

It could become practical tomorrow with a freeze and revive procedure. People who predict the future are destined to be disappointed.

“The purpose of thinking about the future is not to predict it but to raise people’s hopes.”

Freeman Dyson

While you’re certainly entitled to your opinion about whether or not a practical interstellar propulsion technology is currently available, its availability or lack thereof has no bearing on the question of using whatever technology is available to discover and characterize extrasolar planets and develop new technologies in the future. There simply is no logical linkage.

Just as there was no “logical linkage” with your reply to my comment. I made a comment and you made one and I made one and now you are not happy with that. As I have observed, you don’t seem to like what I have to say. That is too bad, you are just going to have deal with it Andrew.

The article is about the search for life on extrasolar planets and your comment right at the top of this thread states “The most important research in this area is not finding these worlds (or systems with asteroid and comet resources for space colonies)- that can wait.” You seem to want to link these two disparate subjects and offer no convincing argument that we can not be doing both.

You seem to be making stuff up about what I “want.”

You need to stop doing that.

This article shows a picture of children playing on an alien world and details the resources NASA is devoting to ostensibly making that depiction a reality. I expressed my view on what NASA should be doing and you are once again trying to shut me down Andrew.

Stop harassing me.

What precisely am I making up? Right in the second paragraph of this article about Nexus it states rather concisely, “…the new Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) will bring together many different experts in a variety of scientific fields to assist in the search for and classification of exoplanets, in particular ones which might be capable of supporting life of some kind.” to which you replied at the top of this thread, “The most important research in this area is not finding these worlds (or systems with asteroid and comet resources for space colonies)- that can wait. The most important research is how to get to them.”

It is right there in print: You rather that research into extrasolar planets should wait and instead there should be research on how to get here. Why can’t we do both?

“The most important research-”

That is my view. It is right there in print and in my first comment at the top of the page. If that is not what you consider most important that is your problem, not mine.

You continue to state what I would “rather” when you are not me, do not speak for me, and refuse to stop inappropriately putting words in my mouth. Now LEAVE ME ALONE YOU INSUFFERABLE NAG.

That is not what you said in your comment. Concerning research into exoplanets (the subject of the article) you said “that can wait”. I believe we can do both and I am asking you why we can not do both? What is the harm?

“Now LEAVE ME ALONE YOU INSUFFERABLE NAG.”

Now who is shutting down whom? I simply want to know why we can research exoplanets and interstellar travel.

NASA’S NExSS teams represent a comprehensive, systematic and logical approach to searching for habitable worlds. It has become quite evident that life forms (most likely microbial) will soon be discoveted. Whether there are planets suitable for humans is another question and best left for future generations.