Forty-five years ago, today, on 7 August 1971, the Apollo 15 crew—Commander Dave Scott, Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Jim Irwin, and Command Module Pilot (CMP) Al Worden—returned to Earth after humanity’s fourth piloted exploration mission to the Moon. During their 12-day mission, the astronauts studied the lunar environment with an extensive battery of orbiting equipment, supported a series of complicated “Moonwalks,” and exploited the first battery-powered Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) to widen their range on the surface as never before. For the first time in the Apollo program, Scott and Irwin supported as many as three EVAs on the surface at Hadley Rille and the Apennine Mountains, the first pair of which uncovered fundamental clues about the Moon’s evolution. The final Moonwalk would be the shortest, but it would help to cement Apollo 15 as one of the grandest missions ever attempted in space science.

As outlined previously by AmericaSpace, the astronauts’ effort to recover a core sample from the lunar regolith had met with some frustration. For a few moments at the opening of EVA-3, their efforts to extract the core tube from the ground were fruitless, and Scott was almost ready to give up. However, with Irwin’s persuasion, both men hooked an arm under each handle of the drill and after several firm tugs the tube sprang from the ground. Precious minutes were wasted, though, when the vice carried on the rover to dismantle the tube into storable sections proved to have been fitted backward. Irwin broke out a wrench and used that instead, but Scott’s frustration was evident. He knew that for every minute wasted before the drive started, they would lose at least another two minutes of geological exploration.

Some of the senior NASA managers in Mission Control wanted to abandon the collection of the core sample entirely. However, the astronauts and Capcom Joe Allen had an ally in Flight Director Gerry Griffin, who had shared several of their geological trips in the California mountains and knew how important the science was and how important the deep core sample was to the success of this mission. It was he who persuaded the managers not to abandon the core tube work. After they had partially disassembled the tube, it was decided that they should leave the remainder of the task to later. When the core was finally opened on Earth, it proved to contain several dozen layers which documented some 400 million years’ worth of lunar history.

At length, Scott and Irwin buckled into the rover and headed west-northwest for a good look at Hadley Rille. After the rille, if time permitted, they hoped to grab an opportunity to inspect the mysterious “North Complex” of craters, which some geologists thought might be a cluster of small, ancient volcanoes. Their arrival at Hadley Rille was truly breathtaking. Its far wall, bathed in the harsh, direct sunlight of the late lunar morning, showed distinct layers of rock pushing through a mantle of dust, lending credence to theories that Mare Imbrium had been built up as a succession of ancient lava flows.

One theory was that the rille was a fracture where the mare surface “opened” like a cooling joint. “But since the scientists have studied the pictures,” Irwin wrote, “the most popular theory is that Hadley Rille was probably a lava tube that collapsed.” All around the two men were enormous slabs of basalt and the geologists in the back room in Houston quickly began pressing for them to move farther downslope, though Joe Allen was becoming nervous. Looking at televised pictures, it seemed to him as though they were right on the edge of a precipice.

In fact, the rille had no dramatic “drop”; rather, it resembled the gentle shoulder of a hill, and they were able to walk downslope without difficulty. “In fact,” Scott wrote, “the slope down which we descended was only about 5-10 degrees and the maximum slope of the rille was only 25 degrees—not steep for such a canyon-like formation.” It was steep enough, however, that from their vantage point they were unable to see the floor.

Time was escaping them (it was “relentless,” Apollo 15 backup commander Dick Gordon once said), and any chance to explore the North Complex very quickly disappeared; that would have to await another generation. Both astronauts found this bitterly disappointing: In Irwin’s mind, it left their excursion only half-complete, whilst Scott would wonder for years afterward if the unique data from the deep core was really worth abandoning the chance to visit the North Complex. At the same time, they appreciated the urgent need to get back to Falcon with enough time to prepare for liftoff later that day.

Back at the lander, with the minutes of the final Moonwalk rapidly winding down, Scott had one last opportunity to give a scientific demonstration to an audience of millions back home. It came from a suggestion by Joe Allen, who was inspired by the experimental work of the great Italian scientist, Galileo Galilei. More than three centuries earlier, Galileo had stood atop the Leaning Tower of Pisa and dropped two weights of different sizes, proving that gravity acted equally on them, regardless of mass. Now, in front of his own Leaning Tower—the slightly-tilted Falcon—Scott performed his own version of the experiment.

“In my left hand, I have a feather,” he told his audience, “in my right hand, a hammer. I guess one of the reasons we got here today was because of a gentleman named Galileo a long time ago, who made a rather significant discovery about falling objects in gravity fields. The feather happens to be, appropriately, a falcon’s feather, for our Falcon, and I’ll drop the two of them here and hopefully they’ll hit the ground at the same time.”

They did … and applause echoed throughout Mission Control.

“How about that?” Scott concluded triumphantly. “Mr. Galileo was correct in his findings!” He originally planned to try it first, to check that it would work, but was worried that it might get stuck to his glove. He decided to “wing it” and, thankfully, it worked. In his autobiography, Irwin would relate that Scott had actually carried two feathers on Apollo 15, one from the falcon mascot at the Air Force Academy. Unfortunately—and much to Scott’s irritation—Irwin accidentally stepped on it! They searched for the feather, but could only find his big bootprints. “I’m wondering,” wrote Irwin, “if hundreds of years from now somebody will find a falcon’s feather under a layer of dust on the surface of the Moon and speculate on what strange creature blew it there.”

Shortly after 9 p.m. EDT on 2 August, a little more than four hours since setting foot on the surface for EVA-3, Scott drove the rover, alone, to a spot a few hundred feet east of the lander. From this place, Mission Control would be able to remotely operate its television camera to record the liftoff of Falcon’s ascent stage. Scott pulled out a small red Bible and placed it atop the control panel of the rover, in order to show those who followed in their footsteps why they had come.

Next, he climbed off the machine and strode toward a small crater. He dug a small hollow and dropped a small aluminum figurine of a fallen astronaut onto the lunar soil. The tiny figurine had been arranged by Apollo 15 command module pilot Al Worden. Meanwhile, Jim Irwin had organized a small plaque, planted alongside, listing the names of 14 astronauts and cosmonauts known to have died doing their duty. The list included Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, together with Vladimir Komarov and the crews of Apollo 1 and Soyuz 11. As he gazed on the plaque, Scott knew he would never come here again. “I had come to feel a great affection for this distant and strangely beautiful celestial body,” he later wrote in his memoir, Two Sides of the Moon. “It had provided me with a peaceful, if temporary, home. But it was time to return to my own home back on Earth.”

Within the confines of Falcon, they had little time to gaze out at the spectacular site of Hadley; only a few hours remained before their 1:11 p.m. EDT liftoff, bound for a rendezvous with Al Worden in the command module Endeavour. It marked the first occasion on which a crew would complete a Moonwalk and perform the liftoff and rendezvous without a rest period in between the two. Having been outside for less than five hours on EVA-3, Irwin wished that Mission Control could have postponed the inevitable by several hours to have enabled them to drive home by way of the North Complex and gather a few samples. Sadly, it was not to be.

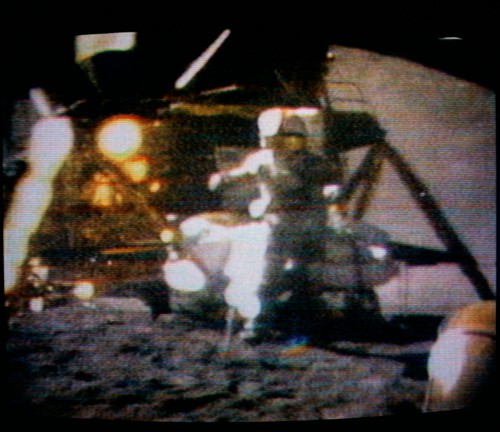

Precisely on time, Scott punched the Abort Stage button and a television audience back on Earth had the chance to actually see an Apollo crew leave the Moon. Falcon’s ascent stage literally “popped” away from the descent stage and shot directly upward with all the speed and accuracy of an express elevator, spraying a shower of fragments of insulation radially outward. One journalist would later compare it to something left over from a Fourth of July celebration. Watching from Mission Control, Chris Kraft—then serving as deputy director of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), today’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas—would gape at the speed of the departure. “I had no idea it went so fast,” he wrote in his autobiography, Flight. “We’d been told it was like that by the other Moon crews, but seeing it for real was a thrilling shock.”

Ten seconds later, a strangely familiar sound came into Scott and Irwin’s earpieces: The Air Force Song, courtesy of Worden, which they had intended to play to Houston only, but which somehow ended up being routed to Falcon, as well. “This was kind of surprising,” wrote Irwin, “because Dave had briefed Al to turn on that music at one minute after liftoff (that first minute is rather critical) but here it came at 10 seconds. It really caused some consternation in Houston. First, they thought somebody was playing a trick in Mission Control, so they conducted a big search. They asked for radio silence—it was a tense situation. Finally, they realized that probably we had turned it on.”

Several days later, on 7 August, Endeavour splashed down safely in the waters of the Pacific Ocean, bringing the lunar explorers safely back to Mother Earth. The months which followed would be challenging for them all. Initially assigned as the backup crew for Apollo 17—the final lunar landing mission—they were abruptly removed from flight status in April-May 1972 and replaced by John Young, Stu Roosa, and Charlie Duke. The reason stemmed from their carriage of 400 unauthorized first-day covers, the proceeds of which were to be invested into trust funds for their children.

Although the agreement with a German stamp dealer went awry within weeks of splashdown and none of the Apollo 15 astronauts accepted any money, they were harshly criticized by NASA and some members of Congress, who demanded an investigation into what they described as “improper conduct.” Although none of the Apollo 15 crew had done anything wrong or illegal, they were stripped of flight status, and Scott fumed that NASA did nothing to dispel (untrue) rumors that they had been fired.

More than four decades after the remarkable scientific extravaganza of Apollo 15—a mission which unveiled more of the Moon’s mysteries than ever before—it is a saddening footnote that this incident continues to resonate. However, the exploration of Dave Scott, Al Worden, and Jim Irwin serves one other purpose: to whet the appetites of future lunar explorers, who may be in college right now, awaiting their chance to visit the mountains of the Moon once again.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will look back at the 25th anniversary of STS-43, an August 1991 shuttle mission which offered glimpses of both the past and future.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

This 4-part series on the Apollo 15 mission underscores and validates the reasons why we, as a species, must continue to explore the cosmos. There is every justification to return to the Moon ahead of an eventual manned trip to Mars and beyond.

Thank you for the trip down memory lane.

Thanks for the informative articles..

Thank you Ben Evans for the informative and thought provoking Apollo 15 articles!

Looking at the nearly full Moon tonight and thinking about Lunar science and our future missions to that nearby and starkly beautiful sphere reminds me of a useful low cost robotic mission launched by the “commercially developed” Athena II.

“Athena II launched the Lunar Prospector to the moon in 1998 and remains the only commercially developed launch vehicle to fly a lunar mission.”

From: http://www.lockheedmartin.com/content/dam/lockheed/data/space/documents/athena/Athena%20Fact%20Sheet%20Review%20vers%204.pdf

“The Prospector Mission team announced in a press conference on March 5th that the tiny, low budget craft has found the answer to one of the most hotly debated questions in lunar science. Prospector HAS found somewhere between 10 to 300 million tons of water-ice scattered inside the craters of the lunar poles. Not only was ice found–as expected–in the Aitken Basin of the lunar South Pole, but also in the craters of the North. To many’s surprise, Prospector detected nearly 50% more water ice in the North than in the South.”

From: ‘EUREKA! ICE FOUND AT LUNAR POLES’ Lunar Prospector Last Updated: August 31, 2001

At: http://lunar.arc.nasa.gov/results/ice/eureka.htm

Note:

“At a cost of $62.8 million, the 19-month mission was designed for a low polar orbit investigation of the Moon, including mapping of surface composition and possible polar ice deposits, measurements of magnetic and gravity fields, and study of lunar outgassing events.” From: ‘Lunar Prospector’ at: Wikipedia

We are heading for an exciting future when many nations, companies, and NGOs will be able to form partnerships of various kinds that can readily afford launching robotic exploration missions to low Lunar orbit and the surface of the Moon.

Getting humans and their Lander to low Lunar orbit will be a useful task for the SLS and international Orion spacecraft.

Supplies for Lunar missions could be launched by a wide variety of launchers, perhaps even by new versions of the low cost Athena launch vehicle.

I’m looking forward to seeing on TV lots of humans and robots on the Moon!