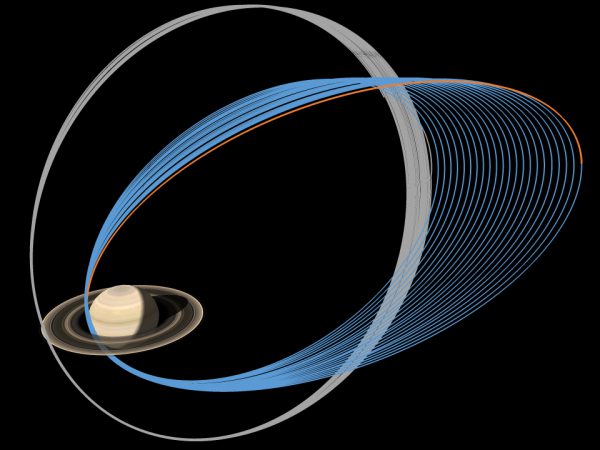

As reported earlier this week, the Cassini spacecraft is now preparing to make a series of very close passes by the edges of Saturn’s rings, known as Ring-Grazing Orbits. Yesterday, Cassini conducted a close flyby of Saturn’s largest moon Titan; this is the second-to-last ever flyby of Titan before Cassini enters the Grand Finale phase of its mission, culminating in a deliberate plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere on Sept. 15, 2017. During this flyby, Cassini focused on mapping the surface and surface temperatures and used Titan’s gravity to help place the spacecraft into the Ring-Grazing Orbits.

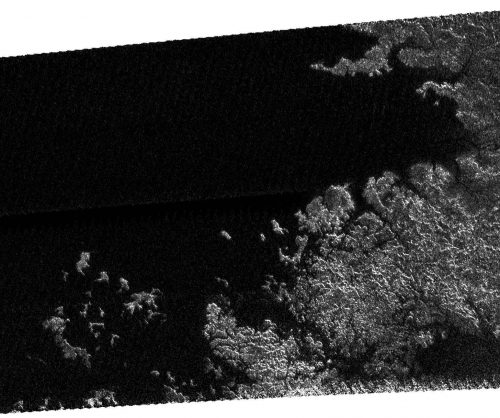

This flyby, called T-125, was used to collect images of the moon’s Xanadu, Hotei Arcus, and Menrva regions with the Visible and Infrared Spectrometer (VIMS). Titan is well-known for its numerous lakes and seas of liquid methane/ethane at the north pole (and also south pole, but fewer). Images taken of the north polar region will be compared to ones from previous flybys to see if there have been any changes in their appearance. In one of the larger seas, a feature called “Magic Island” had previously been observed to appear and disappear; it is still unclear exactly what it is, but theories range from ice floes to waves. Whatever the cause, it shows that there is activity in this cold, wet environment. VIMS will also watch for sun glints off of the lakes and seas, which have been observed before by Cassini. From the update:

“Flyby T-125 has two primary goals: Mapmaking of Titan’s surface, and changing Cassini’s orbit to begin what is perhaps the boldest and most thrilling segment of Cassini’s nearly 20-year mission.”

About halfway through the flyby, Cassini switched to using its Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) instrument. CIRS will be used, for the last time, to take temperature measurements of Titan’s surface, creating a temperature map. Titan is bitterly cold, which is why water ice on the surface is as hard as rock and its “water” is liquid hydrocarbons such as methane and ethane. Titan even has rivers and rain of the same liquid hydrocarbons. CIRS will study the layers in Titan’s atmosphere by looking at the horizon at far-infrared wavelengths, measuring the temperatures of the gases in the layers. By doing so, scientists can determine their composition as well as how the gases and temperatures are layered vertically. Titan’s atmosphere is primarily nitrogen, like Earth’s, but also contains significant amounts of methane and the moon’s surface is perpetually shrouded by a dense haze.

As well as studying Titan itself, Cassini will then use the moon’s gravity to help move it into position for the Ring-Grazing Orbits later on. At that time, Cassini will be in an elliptical (egg-shaped) orbit inclined about 60 degrees from Saturn’s ring plane. During each orbit, Cassini will fly past the outer edge of the F ring at a distance of only about 6,800 miles (11,000 kilometers). The first ring graze is on Dec. 4 and Cassini will perform 20 such orbits. At the end of those orbits will be the final close flyby of Titan, T-126, in April 2017. After that, Cassini is in the Grand Finale phase of its mission.

Yesterday’s flyby of Titan can also be viewed on the Cassini’s Penultimate Flyby of Titan! page on Facebook.

As per the haze mentioned earlier, Titan has been shrouded in mystery ever since its discovery. But now Cassini has revealed this world for the first time, showing it to be more active and geologically diverse than ever thought before. It is a moon which feels more like a planet, with tall mountain ranges of solid water ice, vast dunes of sand-like hydrocarbons, and, of course, the rivers, lakes, and seas of liquid methane/ethane. The liquid hydrocarbons, at extremely cold temperatures, mimic Earth’s water cycle, complete with rain. Radar on Cassini can peer through the thick haze to show the surface below, which at first glance looks amazingly Earth-like with shorelines and riverbeds.

Cassini also recently confirmed methane fog on Titan. Various other theories were proposed as to what was being observed, but were then eliminated by the researchers. According to Christina Smith, a York University postdoctoral researcher, in Discovery News: “We evaluated possible origins. Clouds were considered, but no consistent movement across the frame was detected, so this is unlikely,” Smith wrote. “A superior mirage was considered, but there was no temperature inversion detected on descent so again, this is considered unlikely. We considered a background rise, but due to several considerations our most likely explanation (in our opinions) is that this feature is due to a fog bank rising and falling.”

The Huygens probe, another part of the Cassini mission, landed on Titan in 2005. Although the camera could only point in one direction, rounded boulders of solid water ice, not rock, could be seen in what is thought to be a now-dry riverbed. Huygens was also the first probe to ever land on a moon in the outer Solar System.

Titan is also now thought to have a subsurface ocean of liquid water, just like another moon of Saturn, Enceladus, and Jupiter’s moon Europa, among others. Even Pluto is now thought to have a hidden ocean.

Some scientists think there could be some form of primitive life on Titan, likely methane-based. If so, it would certainly be different from anything on Earth, evolved to live in the cold but wet alien environment.

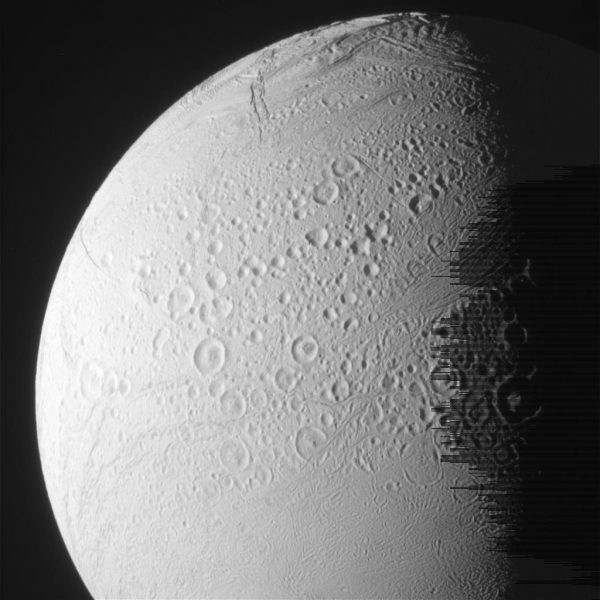

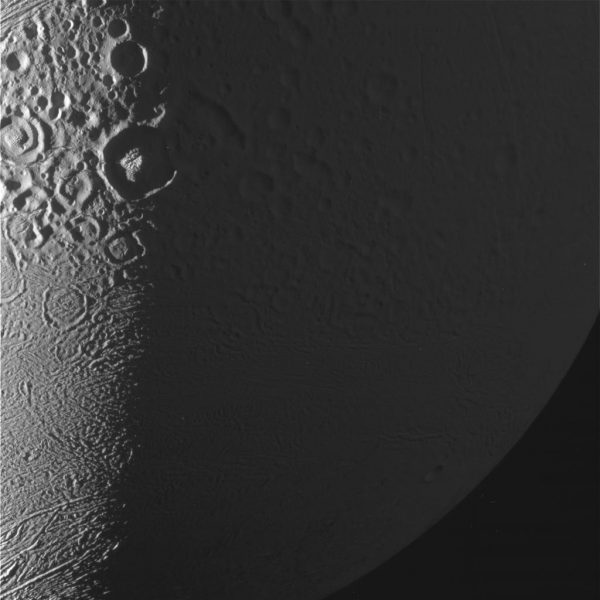

Besides Titan, Cassini also just took new images of Enceladus on Nov. 27, during another flyby. This flyby was not as close as some of the previous flybys, but the images are still impressive. A gallery of all Cassini images of Enceladus can be seen here. The 22nd and final close flyby of Enceladus was on Dec. 19, 2015.

Enceladus is famous as the “ocean moon” of Saturn, since, like Europa, it has a global subsurface ocean of water beneath its icy surface. Massive plumes of water vapor, over 100 known, also erupt from large cracks in Enceladus’ surface at the south pole, which are thought to originate from the ocean below. Cassini has been able to “taste” the plumes by flying through them; so far, the spacecraft has detected water vapor, ice crystals, salts, and various organic compounds in the plumes. Cassini has also found evidence of hydrothermal activity on the ocean floor, similar to what is seen on Earth. With water, heat, organics, and chemical nutrients, Enceladus is now considered to be a primary location to search for evidence of alien life, even if it was only microbes in that ocean.

“This really is a world with a habitable environment in its interior,” according to planetary scientist Jonathan Lunine, at Cornell University.

“We’ve been following a trail of clues on Enceladus for 10 years now,” said Bonnie Buratti, a Cassini science team member and icy moons expert at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “The amount of activity on and beneath this moon’s surface has been a huge surprise to us. We’re still trying to figure out what its history has been, and how it came to be this way.”

As Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., also noted, “Understanding how much warmth Enceladus has in its heart provides insight into its remarkable geologic activity, and that makes this last close flyby a fantastic scientific opportunity.”

“Cassini’s legacy of discoveries in the Saturn system is profound,” she said. “We’ll continue observing Enceladus and its remarkable activity for the remainder of our precious time at Saturn. But these three encounters will be our last chance to see this fascinating world up close for many years to come.”

The results from Cassini’s last close flyby of Enceladus, again passing through the plumes, haven’t been released yet, but should prove interesting once they are. One of the things Cassini was looking for was evidence of hydrogen in the ocean.

“Hydrogen … has the potential to drive the synthesis of organic molecules – and much more,” said geochemist Christopher Glein with the University of Toronto and the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Learning even more about Titan and Enceladus will require follow-up missions, which are now being proposed and planned. As incredible as it was, Cassini did not have the instruments to be able to discover definitive signs of life on either moon. Future missions will, however, and build upon Cassini’s success. Cassini has revealed worlds more complex and diverse than ever thought possible, and it will go down in history as one of humanity’s greatest accomplishments.

More information about the Cassini mission is available here.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

.