June has always been a significant month in the annals of women in space. In June 1963, the first female cosmonaut—Soviet factory worker Valentina Tereshkova—boarded a tiny Vostok capsule and was boosted into low-Earth orbit, spending three days circling the globe and logging more time in space than all of America’s Mercury Seven astronauts, combined. Then, in June 1983, U.S. physicist Dr. Sally Ride flew aboard shuttle Challenger, becoming the first American woman in space. In June 1991, three women flew aboard a spacecraft for the first time. And 25 years ago, this month, in June 1993, Janice Voss and Nancy Sherlock (now Currie-Gregg), two women from civilian and military backgrounds boarded shuttle Endeavour for an ambitious mission of science, technology and spacewalking.

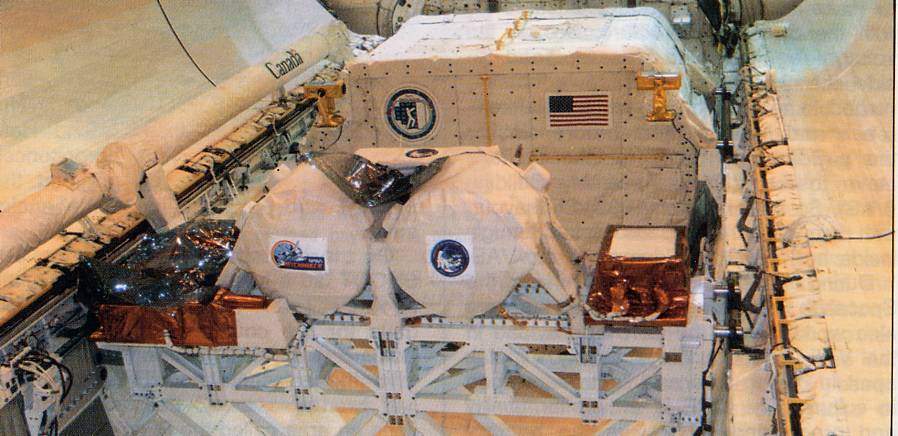

The core objectives of their flight, STS-57, were to recover the European Retrievable Carrier (EURECA)—a free-flying satellite, launched by another shuttle crew, several months earlier—and perform scientific experiments aboard a new commercial laboratory, known as “Spacehab”. The latter would go on to fly several research missions aboard the shuttle, as well as pulling double duty as a logistics facility for flights to Russia’s Mir and today’s International Space Station (ISS). In February 1992, Voss and veteran astronaut David Low were named to STS-57, followed a few weeks later by the rest of the crew: Sherlock, Jeff Wisoff, pilot Brian Duffy and commander Ron Grabe. At the time of the assignment, Duffy was in quarantine at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, days away from his first shuttle launch, so being named to his second flight came as a pleasant surprise. “Jeez, I sure hope I like this,” he asked himself, “because I just signed up for two of them!”

Originally scheduled for late April 1993, delays to the shuttle manifest earlier that year pushed STS-57 into June and eventually to 20 June, which happened to be Duffy’s 40th birthday. Grabe hoped to send his friend over the hill in style with an on-time launch, but it was not to be. Weather conditions at the shuttle’s emergency landing sites were all outside of their mandated limits and, after holding the countdown at T-5 minutes, the 71-minute launch window eventually ran out and the attempt was scrubbed.

Conditions improved the following day and, having shooed an unauthorized aircraft out of the launch danger zone, Endeavour roared aloft at 9:07 a.m. EDT. “The bear jumps off your chest,” recalled first-time flyer Wisoff in an interview for the Smithsonian, “and you can see your seatbelts float upward, which is kinda cool.”

Three days into the flight, after a series of complex maneuvers, the shuttle rendezvoused with EURECA and Low captured the boxy satellite with the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm. However, although the satellite’s solar arrays folded away as they should, its two antennas—which should have automatically retracted and latched—failed to do so. A four-hour spacewalk by Low and Wisoff to rehearse space station assembly tasks was already planned for 25 June and it was decided to send the astronauts outside to manually close the antennas. They completed this task without great difficulty and pressed ahead with a series of space station tasks, evaluating the movement of large masses at the end of the RMS. Interestingly, this was the first shuttle Extravehicular Activity (EVA) to take place on a mission with a pressurized lab in the payload bay, which meant the connecting tunnel between Endeavour’s cabin and the Spacehab had to be closed.

Although no pressure loss was recorded, this closure may have induced an event which scared the daylights out of Grabe, Duffy, Sherlock and Voss on the shuttle’s flight deck. During the EVA, Endeavour’s belly was pointed toward the Sun, in order to simulate the deep cold of space which would experienced during space station construction or repairs of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). “All of a sudden,” remembered Duffy in his NASA oral history, “it was as if somebody took the orbiter and hit it with a bulldozer.” The whole vehicle shook and the four wide-eyed astronauts grew very quiet. There did not appear to be any damage to the shuttle and Mission Control saw nothing amiss in their data.

The most likely explanation was that residual forces had built up on the ground in the struts holding Spacehab in the payload bay and that these had released in space and “rang” through the ship. Outside, Low and Wisoff felt nothing. “They didn’t have a clue,” said Duffy, “but if they’d looked inside at that time, they would have seen eight big eyes!”

Scheduled to run for seven days, STS-57 was extended by 24 hours, due to economical use of consumables, but unsatisfactory weather conditions in Florida forced a further two days of delays. Eventually, on the morning of 1 July, Grabe and Duffy guided Endeavour smoothly back to Earth, touching down at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) at 8:52 a.m. EDT, after a ten-day mission.

The long flight—and the even longer wait to get home—cemented friendships and allowed the astronauts some free time to glimpse the Home Planet. “Nancy and I were on the flight deck, one night,” said Duffy, “when we were waiting to go bed, basically hanging out, and she and I were upstairs, turned all the lights out on the flight deck and the two of us just sat there and floated in the window and watched the Earth going by in the dark. It was pretty neat.” By this stage, so late in the flight, and two days overdue, Endeavour had run out of all of her camera film. But it hardly mattered. “We just got to look,” said Duffy, “and just enjoy it. It was really cool.”