A quarter-century ago, this month, STS-67 set a new record for the longest Space Shuttle mission, an accomplishment which would later be eclipsed by only two other flights in the program’s 30-year history. For more than two weeks in March 1995, three military pilots and four professional astronomers worked around-the-clock in two shifts aboard shuttle Endeavour to bring the distant reaches of the Universe alive with the three ultraviolet telescopes of the ASTRO-2 payload. And even today, the records set by STS-67—a mission length of 16 days, 15 hours and 8 minutes, an astonishing 6.9 million miles (11.1 million km) traveled and 262 Earth orbits—make it the third-longest flight in shuttle program history and the third-longest U.S. non-space station voyage of all time.

Flown by Endeavour, the youngest of the orbiters, STS-67 also stole the crown from queen-of-the-fleet Columbia, which had secured and held records for the longest shuttle missions ever since her maiden voyage in April 1981. Columbia was the first to be equipped with Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) capability, allowing her to undertake flights of 16 days or more, and accordingly scooped up most of the longer missions in shuttle program history. When the STS-67 crew was announced, the flight was expected to be flown by Columbia in December 1994. But changes to the shuttle manifest during the course of that year prompted NASA to put its oldest orbiter into an earlier-than-scheduled period of maintenance and refurbishment. STS-67 was instead reassigned to Endeavour, which had been fitted with EDO capability during her initial construction and was therefore more than capable of supporting a long mission.

As its name implied, ASTRO-2 was a reflight of the ASTRO-1 mission, which featured the Hopkins Ultraviolet Telescope (HUT), the Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (UIT) and the Wisconsin Ultraviolet Photopolarimeter Experiment (WUPPE) to observe celestial sources within our Solar System and further afield in the cosmos. But for the tragic loss of Challenger, ASTRO-1 might have flown in March 1986 for extended observations of Halley’s Comet. When it eventually flew on STS-35 in December 1990, ASTRO-1 suffered technical issues with its pointing system, yet still achieved an 80-percent scientific success rate and observed 135 of 250 planned targets. Six months later, NASA announced that this “proven scientific performer” would fly again in 1994.

Crew assignments for ASTRO-2 began in August 1993, when astronomer Tammy Jernigan was named payload commander, to be joined in October by fellow astronomer John Grunsfeld as a mission specialist. Finally, in January 1994, the seven-member STS-67 crew was rounded out with the assignment of ASTRO-1 veterans Sam Durrance and Ron Parise as payload specialists, Bill “Borneo” Gregory as pilot, Wendy Lawrence as the flight engineer and veteran shuttle flyer Steve Oswald as mission commander. Plans for the mission to launch as soon as December 1994 came to nothing, following Endeavour’s dramatic pad abort that August which pushed her line-up of follow-on flights correspondingly to the right. By the start of 1995, launch of STS-67 was targeted no sooner than 23 February, with an expectation that its baseline 15 days and 13 hours duration would easily exceed the previous shuttle endurance record set by the STS-65 crew a few months earlier.

Delayed a few days into early March, Endeavour was eventually primed to fly in the small hours of 2 March, although Air Force meteorologists predicted an iffy 60-percent chance of acceptable weather. Nevertheless, Oswald led his crew out of the Operations & Checkout Building at 10:20 p.m. EST, bound for Pad 39A. By midnight, all seven astronauts were aboard the shuttle and liftoff was delayed only slightly by a problem with the Flash Evaporator System secondary heater. Endeavour speared into the night at 1:38 a.m. EST, in what Gregory later described as “instant daylight”. Sitting at the back of the flight deck, Lawrence and Grunsfeld used a hand-held mirror to watch the Florida coastline recede away from them in a glow of exhaust flame.

“Liftoff of Endeavour,” exulted Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Public Affairs Officer (PAO) Lisa Malone, “on a voyage to view the Universe.”

That voyage commenced as soon as the shuttle achieved orbit. Within hours, the crew divided themselves into two 12-hour shifts—Oswald, Gregory, Grunsfeld and Parise labeled “red”, Lawrence, Jernigan and Durrance as “blue”—to activate the ASTRO-2 payload and commence astronomical observations. It was a busy time as the crew converted Endeavour from a launch vehicle into a spacecraft and workplace for the next two weeks. “It never ceases to amaze me,” Oswald told a Smithsonian interviewer, years later, “the fire drill that goes on down in the middeck in those first couple of hours after we reach orbit.” As the mission commander, it was Oswald’s task to figure out how much extra time needed to be added to the schedule, based on how many “rookies” were aboard, and which crew members were affected by space sickness. “Sometimes guys are semi-Velcroed to the wall, throwing up,” he added, “while the folks you least expected to be heroes are just chugging along, executing the plan.”

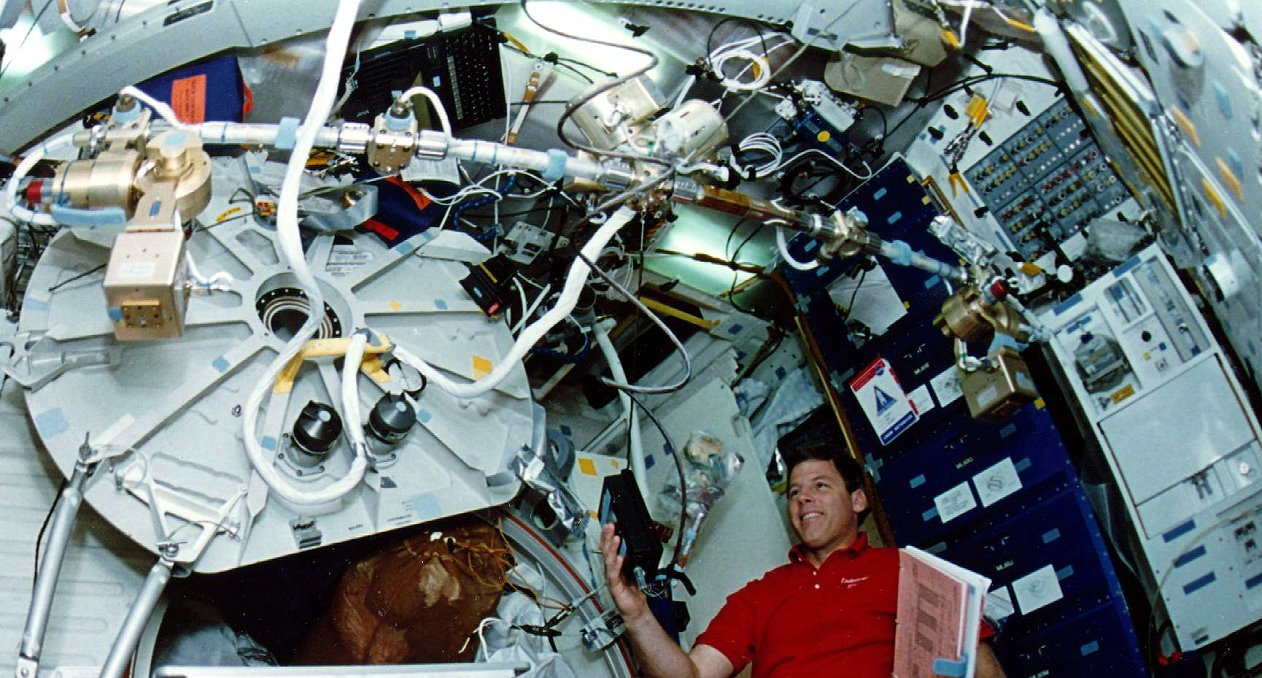

All told, the three ASTRO-2 telescopes totaled 17,380 pounds (7,885 kg) and were fastened in place onto a pair of Spacelab pallets in the shuttle’s payload bay. Jernigan oversaw the deployment of the Instrument Pointing System (IPS) and Durrance powered-up the telescopes. Early activities proceeded normally, despite a Reaction Control System (RCS) thruster leak, which twice forced the closure of the telescopes’ aperture doors to safeguard their optics from contamination. The mission suffered from none of the IPS pointing troubles which had plagued ASTRO-1 in December 1990. According to NASA’s STS-67 press kit, a special test team was assembled at the Marshall Space Flight Center(MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala., and this “extensively modified and tested the IPS software and made other improvements to ensure the IPS works properly for ASTRO-2.” Specifically, an image motion compensation system—designed to eliminate the effects of “jitter”, induced by crew movements and thrusters firings—helped to refine instrument pointing and stability for the telescopes.

This was particularly vital in the case of UIT, whose images were recorded on film with the individual exposures lasting as long as 30 minutes. WUPPE experienced a somewhat slow start, however, since the activation and verification of its detector was delayed by problems keeping it aligned with a test target. Twelve hours into the mission, controllers at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, declared the IPS fully operational and transferred control of its equipment to the ASTRO-2 payload team at Marshall. With this transfer, Grunsfeld and Parise began the “Joint Focus and Alignment” procedure to ensure that all three instruments could point in precisely the same direction.

Despite the day-long process of calibration, astronomical observations of the ultraviolet sky got underway with pace and gusto. Early on 3 March, the HUT and UIT science teams had locked their instruments onto the Cygnus Loop, an ancient supernova remnant, with the former instrument gathering temperature, density, and chemical data and the latter imaging “filaments” of excited gas and energizing shockwaves. WUPPE demonstrated that its optics were in perfect working order by observing a calibration star, Beta Cassiopeiae, followed by a study of the hypergiant luminous blue variable star P Cygni. Meanwhile, HUT examined EG Andromedae, a “symbiotic” system of a relatively cool, orange giant star and a tiny, exceptionally hot blue star.

White dwarfs, globular clusters and “Wolf-Rayet” stars formed the center of attention over the following days. The latter include EZ Canis Majoris and are thought to represent one of the final phases in the evolution of supermassive stars, whose luminosities vary between 100,000 and a million times as bright as our Sun. Their powerful ionized-gas emissions, or “stellar winds”, were believed to accelerate their aging process.

Extremely bright Seyfert galaxies, distant quasars, and interactive binary stars also received attention. In the latter case, WUPPE observed an X-ray binary, known as Vela X-1, with astronomers speculating that a neutron star was gravitationally “stripping” material from its companion star, causing a large oval disk to form in orbit. Polarization measurements by WUPPE enabled measurements to be made of the size and shape of this disk, as well as calculations as to the quantities of mass transferred between the two companions.

Closer to home—and illustrated on the STS-67 crew’s mission patch, which was chiefly designed by Gregory, Grunsfeld and Lawrence—the largest planet in the Solar System, Jupiter, also fell under ASTRO-2 scrutiny. HUT investigators focused on its immense magnetosphere and its volcanically active moon, Io. A recent eruption on Io had deposited material onto the surface and into its tenuous atmosphere, prompting HUT co-investigator Paul Feldman to seek evidence of changes in the number of sulfur and oxygen ions in its environment. “As Io orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours,” noted one of NASA’s news summaries, early in the mission, “some of this material is left behind, forming a donut-shaped torus of sulfur and oxygen plasma around Io’s orbit.”

The sheer “strangeness” of the Universe was illustrated by the peculiarities of so many ASTRO-2 targets. Phi Persei, a hot, rapidly spinning star, exhibited an unusual ultraviolet spectrum, possibly due to a “shell” of gas which may have been an outer layer shed by its fast rotation. Two active Seyfert galaxies, both strong emitters of very bright ultraviolet radiation and thought to have supermassive black holes at their hearts, were studied; one of them, NGC 4151, was five times brighter in March 1995 than it had been when ASTRO-1 observed it, more than four years earlier. Indeed, the galaxy exhibited a 10 percent luminosity increase in a matter of days during ASTRO-2.

Ancient stars and young stars, stellar graveyards and stellar nurseries came under the observatory’s ultraviolet gaze, including an open cluster called N4, whose youthful occupants were believed to be less than 10 million years old. Elsewhere, M104—a distinctive spiral galaxy, nicknamed “The Sombrero Galaxy”—was observed, with star-forming regions thought to reside within its “brim” and older stars (and maybe a black hole) within its “crown.”

Periodically, Jernigan was overtaken by a sense of childlike wonder at the environment in which she found herself. “There was a lot of time when the cockpit was darkened,” she remembered in an interview with the Smithsonian, years later. “You would monitor observation of an object for maybe 20 minutes before you had to regroup, repoint the Instrument Pointing System and set up the instruments again. There were whole blocks of time where you could just look out and reflect, talk to the other crew members who were awake on your shift and really have a sense of what a beautiful Universe we inhabit.”

One crew member who proved particularly valuable—“a tremendous source of knowledge,” according to Steve Oswald—was Parise. Both he and Durrance were non-professional astronauts, but both had served as payload specialists on ASTRO-1 and had trained extensively with the instruments. On-orbit, both men assisted the other crew members to don and doff their suits at the beginning and end of the mission, but during ASTRO-2 science operations their support was indispensable. There was room for fun and ribbing, too, with Oswald describing Parise’s age and experience. “When we got back to Ellington, I said he had been assigned to ASTRO since the Earth cooled,” joked Oswald, “and that’s not really completely accurate. However, he has been working ASTRO since he graduated from college, which was shortly after the Earth cooled!”

Ironically, Oswald and Parise were separated in age only by about five weeks.

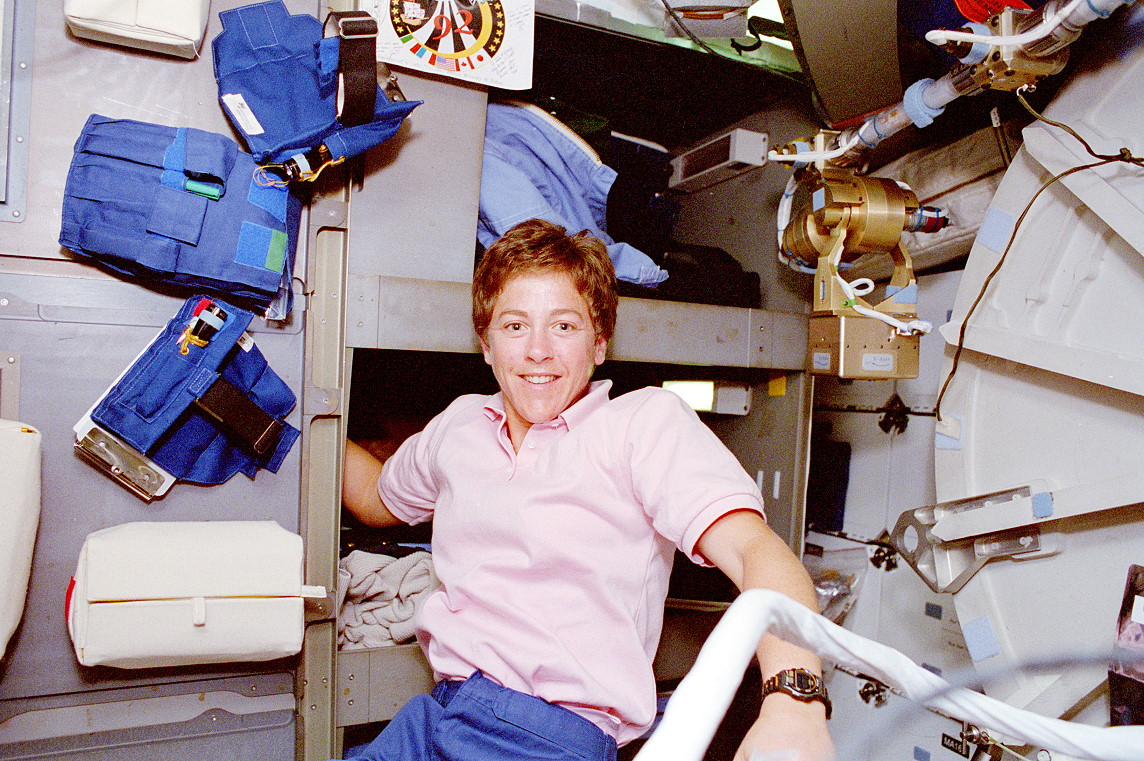

If the scientific wonders of the mission were a thing of beauty on STS-67, then so too was the overall experience of flying in space. “How many people,” Lawrence rhetorically asked, “can say they’re living their dream?” With a 24-hour operation underway, the presence of four phone-booth-sized sleep stations in Endeavour’s middeck provided a welcome area to rest. “Keep in mind that while half of the crew is up and working, the other half of the crew needs to be asleep,” said Lawrence. “The sleep stations really provided you with a great way to get a good, quiet night’s sleep. Personally, I never used earplugs and I slept great on-orbit.” Each day, the teams would try to gather for dinner, with the red shift kicking off with a shrimp cocktail. On one occasion, their blue shift counterpart Durrance—“who probably didn’t have enough breakfast,” Steve Oswald quipped at the post-flight press conference—even snuck in to partake.

In a sharp contrast with the technical difficulties experienced by its predecessor, the ASTRO-2 observatory was also a beautiful payload, from the standpoint of systems performance, with the IPS and its Image Motion Compensation System (IMCS) performing “in an outstanding manner,” according to NASA’s official post-mission report. “The IPS and IMCS for the first time achieved operational capacity,” exulted ASTRO-2 Mission Manager Robert Jayroe, then quipped: “In my estimation, the IMCS and IPS teams have done everything but make the hardware stand up and do a tap dance!” The WUPPE team gathered more than three times as much data as had been gathered during ASTRO-1, whilst the UIT investigators reported that all planned celestial targets had been acquired and the HUT scientists announced more than 100 successful observations.

Of added note was the fact that astronaut Norm Thagard—who flew with Oswald on STS-42 three years earlier—had recently arrived aboard Russia’s Mir space station as its first U.S. resident. And a unique ship-to-ship communications session was arranged between the two former crewmates.

“Dr. Thagard, I presume?” Oswald playfully quipped. “I was wondering how your English was by now, Normie, but it sounds like you haven’t forgotten a thing.”

“You know, I figured if we were ever in orbit again, we’d probably be on the same spacecraft,” replied Thagard. “I guess I was wrong!”

Already scheduled for more than 15 days aloft, the crew quietly eclipsed the previous shuttle duration record on the evening of 16 March, with the expectation that Endeavour would make landfall at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) at 3:09 p.m. EST on the 17th. However, it was not to be. Unacceptable weather conditions in Florida forced the Mission Management Team (MMT) to scrub the attempt and reschedule it for the 18th.

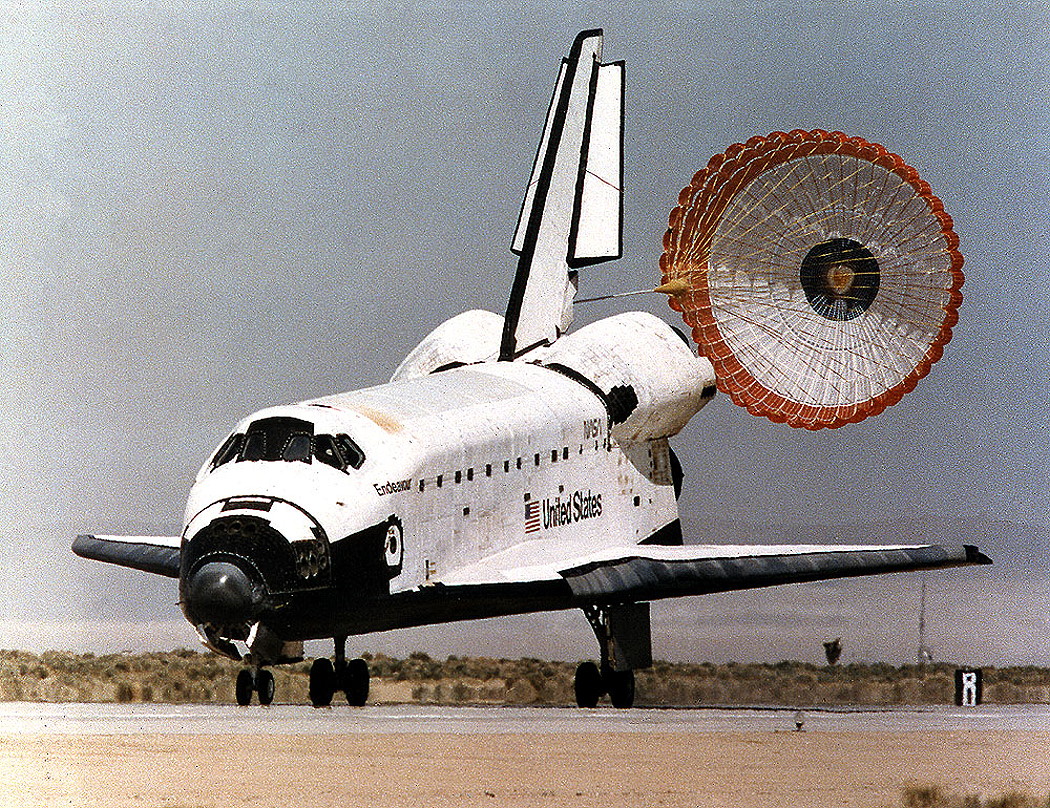

With the situation on the East Coast showing little evidence of improvement, it was decided to divert to Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., instead. Already, STS-67 had passed the 16-day mark, which was the maximum “standard” length for an EDO mission, and managers were anxious not to press Endeavour’s consumables any further. Sweeping across the Pacific Ocean, the orbiter entered U.S. airspace at the California coastline and alighted on Runway 22 at Edwards at 1:47 p.m. PST (4:47 p.m. EST), concluding a remarkable mission, which had lasted just a few hours shy of 17 full days.

For Oswald, it was a nice record to end his astronaut career. Yet the months of preparation had taken their toll. “The training is structured such that it trains to the lowest common denominator,” he explained in a NASA Tacit Knowledge Capture interview, “and it just takes forever. You’re going through all the stuff again for those that haven’t flown before. It got to be kind of a long, drawn-out deal. It was a great flight, great crew; I had a great time, but afterwards, I was just done.”

An interesting side note for STS-67 was that, for the first time, an orbiter other than the queen of the fleet, Columbia, had secured the shuttle program’s longest mission. Since the maiden voyage of the reusable spacecraft in April 1981, Columbia had maintained a crown for herself in terms of the longevity of her missions. Kicking off the shuttle era for two days on STS-1, she steadily increased her endurance to eight days on STS-3 in March 1982, 10 days on STS-9 in the late fall of 1983, almost 11 days on STS-32 in January 1990, 14 days on STS-50 in mid-1992, and—on STS-65 in July 1994—just a few hours shy of 15 full days in orbit. STS-67 thus knocked Columbia off the endurance top spot, but not for long. In July 1996, she once more secured the record, by flying a mission of 16 days and 22 hours, an achievement pressed yet further by one of her later crews in December of that year, who spent 17 days and 15 hours in orbit. This latter record stood until the very end of the shuttle’s 30-year career in July 2011. It is therefore a matter of pride for the STS-67 crew that their mission retains its place as the third-longest in shuttle history and—excluding long-duration expeditions by NASA astronauts to Skylab, to Russia’s Mir space station, and to the International Space Station (ISS)—also ranks third on the list of the longest U.S. “solo” space missions of all time.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

should be https://historycollection.jsc.nasa.gov/JSCHistoryPortal/history/oral_histories/SSP/OswaldSS_5-20-08.htm not http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SSP/OswaldSS_5-20-08.htm

I saw both flights take off , will always recall how great it was.