Four decades have now passed since one of the most dramatic reversals in fortune in American space history: the salvation of Skylab. On 14 May 1973, America’s first space station was launched into orbit atop the final Saturn V booster, but an unfortunate sequence of events led to the premature deployment of its micrometeoroid shield, which was promptly ripped away in the supersonic airstream, together with one of two solar arrays. The other solar array was so clogged with debris that it was “pinned” to the side of the station. For ten days, engineers battled to come up with a workable plan whereby Skylab’s first crew—astronauts Pete Conrad, Joe Kerwin, and Paul Weitz—could effect a successful repair and keep the crippled station on the straight and narrow.

Before the rescue could get underway, Skylab had to be depressurised and repressurised with nitrogen four times over three days in order to purge any toxic gases from its atmosphere. One of the most hazardous materials was a heavy layer of polyurethane foam, bonded to the internal walls, and Conrad, Kerwin, and Weitz would wear masks upon entering Skylab and perform checks to ascertain the station’s environment. As their scheduled 25 May launch date neared, the storage lockers of the command module were filled with additional items: extra cameras, new medical supplies, film cassettes, tools to free the jammed solar array, and equipment to detect poisonous gas.

For Gene Kranz, who had sweated out the traumatic days of Apollo 13 from the flight director’s console, Skylab was no less exciting than going to the Moon. Years later, he related that people often refused to believe him. “Skylab to me was a different type of focus,” he told the NASA oral historian, “as a leader and focus as a team. The Apollo missions were all short, on the order of ten days or so, and it’s one thing to hold a team together and … keep the quality for ten days, even though it’s very intense. It’s another thing to keep this team together for the best part of a year and to hand over not tens, but literally hundreds of problems, every shift, without a glitch!”

With their launch scheduled for the stroke of 9 a.m. EST, the morning of 25 May was particularly peaceful for the three astronauts. “This was the least well-attended Apollo launch in history,” Joe Kerwin recalled, “because everybody had to go home and put the kids back in school. We arrived at the command module and looked inside and it was a sea of brown rope under the seats and under the brown ropes were all these different umbrellas and parasols and sails and also the equipment that we had selected to try and free up the solar panel, which was a pretty eclectic collection of aluminium poles that could be connected together, and a Southwestern Bell Telephone Company tree-lopper with brown ropes to open and close the jaws. Some of it we’d seen, some of it we hadn’t!”

The astronauts were unperturbed. Indeed, as the Saturn IB cleared the tower and roared into the clear morning sky, Conrad declared that his crew could fix anything. Launch came precisely on time and kicked off an eight-hour orbital ballet to rendezvous with the crippled Skylab later that same afternoon. An initial orbit of 357 x 156 km was gradually refined by four manoeuvres to fly a near-circular, 424 x 415 km path to intercept the space station on their fifth orbit. “Up until this time,” recalled trajectory and rendezvous specialist Cathy Osgood in a NASA oral history, “our rendezvous [procedure] had been to rendezvous the first day, after about five orbits. If you didn’t rendezvous by about the fifth orbit, the astronauts’ work day had been so long that they’d have to be facing a docking situation when they were just absolutely exhausted; so, all up until this time, the astronauts themselves wanted to get it all done the first day.”

Little did anyone know that the first day in space for Pete Conrad and his crew would run to no less than 22 hours.

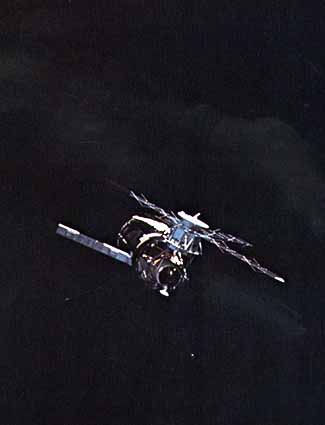

Conrad’s call of “Tally-ho the Skylab!” as a steadily brightening star on the horizon drew closer masked, at first, the seriousness of what the astronauts were about to face. The micrometeoroid shield was gone, as was one of the two solar arrays, whilst the second was so jammed with debris that it could not deploy properly. “When Pete finally got a good look at Skylab,” Nancy Conrad wrote, “he got the same feeling as you would when seeing a classic car you’d invested four years of your life in restoring now mangled in a heap in the town junk yard.” As Weitz took pictures, Conrad performed a flyaround inspection of the station, quickly ascertaining that the scientific airlock was not cluttered with debris, thereby making the deployment of the Johnson Space Center’s parasol a realistic option, and asserting his conviction that a stand-up EVA with the cable cutter should be enough to free the jammed solar array.

The first order of business was a “soft docking” at Skylab’s forward port at 5:56 p.m., engaging capture latches but not retracting the command module’s docking probe to ensure a firm metallic embrace. For a few minutes, the astronauts ate a quick dinner and prepared for the stand-up EVA. “A full hard dock wasn’t desirable at this point,” wrote David Hitt, Owen Garriott, and Joe Kerwin in their book Homesteading Space, “because of the likelihood that they’d undock again shortly. The docking system needed to be dismantled and reset after a hard dock.” With all three men fully suited, Conrad undocked from Skylab at 6:45 p.m., depressurised the cabin, and opened the side hatch. With Kerwin hanging onto his ankles to provide stability, Weitz reached out and used the modified tree loppers and a kind of “shepherd’s crook” to free the jammed array. It should have been an occasion of euphoria for Weitz, who had not been scheduled to perform an EVA at all on this mission. Unfortunately, despite his sterling efforts, it did not go well.

At first, he positioned himself with his upper body poking through the hatch. Kerwin passed him three sections to assemble a 4.5 m pole with the loppers at the end, whilst Conrad kept the spacecraft steady. “We had seen … that there was a piece of bolted L-section from the thermal shield that had been wrapped up around the top of the solar wing,” Weitz recalled in his oral history, “and apparently the bolt heads were driven into the aluminium skin. We thought maybe we’d just break it loose, so we got down near the end of the solar array and I got a hold of it with the shepherd’s crook.” However, as Weitz heaved on it, he was actually pulling the command module towards Skylab. In the meantime, Conrad had the unenviable task of keeping the spacecraft a mere 60 cm from the station … and preventing the unwanted oscillations from causing a collision. The work was harder because a third of his field of view was blocked by the command module’s open hatch.

“It made for some dicey times,” Weitz later recalled. As the two vehicles entered orbital darkness, he paused in his work, then resumed as they flew within range of the tracking station. The shepherd’s crook was getting him nowhere and the torrent of four-letter words from all three astronauts even prompted the capcom in Mission Control to ask them to modify their language; for they were on an “open mike.”

The main problem, Conrad explained, was that a strip of metal had become wrapped across the solar array during the separation of the micrometeoroid shield. Its bolts had tangled themselves in the array and none of Weitz’s actions to cut the strap, even with the loppers, were having any effect. “Rather than cutting it across the short way, we were trying to cut along the long way,” Weitz said, “and didn’t have enough muscle with that thing, because it was six or eight feet out ahead of me and I was pulling on a line to try to do it.” The metal strap, ironically, was only a few centimetres wide, but it was riveted fast and Conrad knew they did not have a hope of breaking it using the tools in the command module.

The attempt was scrapped and, after 40 minutes, the astronauts were instructed to close the hatch and re-dock with Skylab. Even this proved easier said than done: getting the pole, loppers, and shepherd’s crook back inside in a safe and speedy manner led to an inadvertent thump to Conrad’s helmet and an accidental kick to Kerwin. The capcom’s advice to modify their language again fell on deaf ears, as a few more “unscientific” words were uttered. …

Docking, wrote Nancy Conrad (probably selecting a few of her late husband’s words), “was a bitch.” On their first attempt, the probe did not engage with the drogue and no fewer than three further tries were also fruitless. “Pete gave Weitz the controls,” Nancy continued, “depressurised the command module, and opened the tunnel hatch. He and Joe dove head-first into the bank of circuits and gizmos, Pete cussing a blue streak as he sorted through wires, cutting and splicing like a pissed-off Maytag repairman trying to get a dryer to work again.” Weitz then set about rewiring in the right-hand equipment bay, removing the electrical inter-lock which prevented the main latches from actuating until the capture latches were secure. After an hour or so of re-routing and connecting wires, bypassing electrical relays for the capture latches on the tip of the probe, skinning knuckles—and another bout of undesirable vocabulary—Conrad used the service module’s thrusters to bring the two collars into direct contact, triggering a dozen capture latches in a cacophony like machine gunfire.

They were at Skylab to stay.

In their oral histories, both Kerwin and Weitz paid tribute to a conversation with their rendezvous instructor, Jake Smith, in February 1973, in which the minutiae of how to accomplish this kind of “backup docking procedure”—which wires to cut and which to splice together—had been explored. Had it failed, there was a very real possibility that the mission would have ended. Now, though, with Apollo safely docked, an ecstatic Mission Control were able to advise the crew to grab a bite to eat and some sleep before entering Skylab the following morning. It was 11:50 p.m. EST. Their first day in space had been a long one—more than 22 hours, prompting Paul Weitz to quip that “union rules wouldn’t allow us to work that long anymore!” Surprisingly, neither of the rookies had gotten sick. Joe Kerwin had taken a pill shortly after reaching orbit, determined that he would not throw up and would not screw up the mission … but, despite the tense nature of those 22 hours, both he and Weitz adapted well to the weightless environment. Making his fourth space mission, Pete Conrad had no problems whatsoever.

Next morning, the crew opened the hatch and Weitz, as the systems specialist, was the first to enter Skylab. Pressure checks and air sampling gave the atmosphere a clean bill of health. The multiple docking adaptor and airlock were cool, at just 13 degrees Celsius, but all three men knew that the unprotected interior of the station would be hotter and less comfortable. Conrad and Weitz stripped “down to our skivvies” and opened the hatch into the darkened workshop at 3:30 p.m. EST to deploy the parasol through the scientific airlock. “It didn’t take very long until we figured out why people in the Sahara Desert wear a lot of loose clothing,” reflected Weitz, “because … soon we had long trousers on and shirts and jackets and hats and gloves and the whole thing.” The temperature was 55 degrees Celsius—“rather warm,” the two men noted—and although there was no evidence of toxic gas and the air was safe to breathe, Skylab’s humidity was low and they could only remain inside the stifling oven for 15 minutes at a time. Periodically, they had to retreat back to the relative comfort of the multiple docking adaptor for a breather.

At length, the parasol was assembled and at 7:30 p.m., its rods were threaded through the aperture of the scientific airlock into vacuum. Next, the parasol emerged, folding out like a big patio umbrella. However, one of its four folded arms did not swing out properly and Kerwin, watching from inside the command module, expressed dismay when he saw it had only deployed to cover two-thirds of its required area. “It’s not laid out the way it’s supposed to be,” a dejected Conrad told Mission Control. The parasol was askew and crinkled in places. Nevertheless, Houston assured the astronauts that the wrinkles had probably set in during the coldness of the lengthy deployment, which took place during orbital “night-time,” and, as the material heated up in sunlight, it would spread out fully.

“I think the ground noticed the temperatures coming down,” Weitz recalled. “Within an hour, they could tell.” Overnight on 26/27 May, temperatures on the exterior of Skylab dropped by 55 degrees Celsius and the interior by 11 degrees Celsius. Eventually, the interior temperature stabilised at around 30 degrees (close to a normal day in Houston) and the astronauts could even tell where the parasol lay on the outer hull, by running their hands along the inner wall and feeling the difference in temperature. For the first couple of nights, Conrad and Kerwin elected to sleep in the command module, whilst Weitz tied his sleeping bag in the multiple docking adaptor, “because it was cooler there and you had a lot more room besides.” Scientific work could now begin, although electrical power remained an issue and was rendered more acute when the ATM arrays were taken out of direct sunlight on 30 May, leaving Skylab reliant upon battery power.

An EVA was needed to fix the clogged array. Under the direction of backup commander Rusty Schweickart, a repair scenario was devised. It required Conrad and Kerwin to move to the antenna boom at the forward end of Skylab and attach a cable cutter to the debris; this would serve as a makeshift “hand rail” to enable them to reach the jammed solar array and cut the metal strap. Once there, they would have to break a frozen hydraulic “damper” on the array. The damper’s purpose had been to prevent the array from deploying too fast, but when it partially unlatched after launch, the hydraulic fluid quickly froze solid. Conrad and Kerwin would connect a Beam Erection Tether (BET, effectively a nylon rope with hooks on each end) between the array and the airlock. When the debris had been removed, it was hoped that pulling on the tether would break the damper. During a series of simulations on 2 June, Schweickart and fellow astronaut Ed Gibson practiced the procedure and found that, aside from a lack of foot restraints, it was workable.

The lack of foot restraints, and lights, hand-holds, and visual aids, was not an oversight; it reflected the fact that there had never been any intention to perform maintenance on Skylab. There were several planned EVAs, for example, to replace film cassettes, but actual repairs were considered too dangerous. “I had been working a lot of the spacewalk procedures for the film retrieval,” Gibson told the NASA oral historian, “so it was natural to then start developing procedures for the repair of the station.”

However, some managers remained jittery about the idea of attaching a cable cutter to debris, and eight metres away, at that, but there was little alternative. On the evening of 4 June, Schweickart talked Conrad through the task and, as the astronauts slept, a list of tools and assembly instructions were transmitted to Skylab’s teleprinter. The crew reviewed these procedures and rehearsed the steps inside the station on 6 June, with a suited Kerwin, minus his helmet, practicing the movement of the poles and grabbing a mock target with the cutters, before finally venturing outside in the early hours of the following morning.

Since the airlock was in the middle of the Skylab “cluster,” the fully-suited Weitz had to ensure that Conrad and Kerwin had all of their tools and tethers before he depressurised them. Weitz then retreated into the multiple docking adaptor. The hatch was opened at 10:23 a.m., just before the station entered the dark portion of its orbit. Conrad assembled the tools—six 1.5 m rods screwed together, the cable cutter fitted, and several metres of rope from the backup SEVA sail tied to the cutter’s pull rope—and then he and Kerwin moved into position alongside the antenna boom. The unlikely contraption thus enabled them to operate the cutter from several metres away … just enough to reach the jammed array.

As Kerwin tried to close the cutters against the debris, it became apparent that he was “slipping,” because he could not establish a secure position for himself. For half an hour, with one hand steadying himself and the other trying to close the cutters, he struggled fruitlessly to complete the work. As his pulse rate began to climb, he decided on an alternative course of action and shortened his own tether, in an effort to steady himself against the edge of the station. It worked and after ten minutes he was able to tell ground controllers that the cutters were securely fastened to the debris. Next, he pulled on the lanyard to operate them … but nothing happened. Conrad inched his way, hand-over-hand, along the length of the beam to see what was amiss, and precisely as he reached the cutter “end,” the jaws snapped shut, freeing some of the metal strap at 2:01 p.m. and hurling him “ass over teakettles” into space. Fortunately, Conrad’s tether restrained him from moving far from Skylab, and the jammed array now stood at 20-degrees-open.

The frozen damper, however, still resisted normal deployment and the holes on the solar array were smaller than on the ground model, so he could only attach one of the two hooks on the BET. The two men heaved on the tether, but without success, until Conrad placed his feet on the frozen hinge, stooped to fit the tether over his shoulder and “stood up.” Kerwin pulled on the tether and, this time, the solar array suddenly released and sprang into its full, 90-degrees-open position. Both astronauts were flung outwards by the catapult-like effect and arrested by their tethers. After three hours and 25 minutes, the two laughing astronauts re-entered Skylab … and the needles of the electricity meters dramatically jumped, signalling success. By the next day, 8 June, solar heating had fully extended the array and it was generating 7 kW of much-needed power. From just 40 percent power, the station’s output suddenly increased to around 70 percent.

NASA’s confidence in the abilities of spacewalking astronauts increased substantially. “Before that, there was still the legacy of problems with EVA during Gemini,” recalled Rusty Schweickart. “Apollo, of course, made a big difference, but that was sort of running around on the [lunar] surface in gravity again; so here was EVA of a massive scale in weightlessness that we never anticipated; [we] did it with flying colours, everything worked just fine, never had a problem and saved the mission.” For Kerwin, his first spacewalk was electrifying—there was nothing, he said later, which could possibly compare to looking at the Earth through the visor of a space suit—but also demonstrated that the underwater training on the ground was harder than the real thing in orbit. “No matter how well they weight you out” in the water tank, he said, “you’re not really weightless. If your body is turned upside down, yes, the suit is neutrally buoyant, but you’re jammed up against the shoulders and the blood is rushing to your head. If you can do it under those circumstances, you’re going to find that it’s a piece of cake in zero-G.”

Saving Skylab was a personal triumph for Pete Conrad. Between May 1973 and February 1974, three crews would occupy the station for as long as three months at a time and would contribute enormously to humanity’s understanding of the weightless environment and the influence of the Sun upon our planet. Conrad’s first three space missions had each been filled with drama—a record-breaking Gemini flight, which exceeded the Soviets for the first time, an intricate orbital rendezvous, and an adrenaline-charged lunar landing—but it was for none of these that he received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 1978. It was Skylab which propelled him to his greatest professional height and his greatest personal accomplishment … and the Congressional accolade paid tribute to Conrad’s devoted command of the singular mission which saved America’s first space station.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next weekend’s article will commemorate the anniversary of Project Juno in May 1991, during which Helen Sharman became Britain’s first astronaut … and marked out the U.K. as the first of only three nations to date to have a woman as its first space traveler.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter:@AmericaSpace

Missions » Apollo »

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:United States and North American News | David Reneke | Space and Astronomy News

Pingback:Skylab’s Long-Haired Messenger: The Visitation of Comet Kohoutek « AmericaSpace