CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla — Eclipsed by other space-related events, the story that the first launch of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program had slipped from 2015 to late 2017 has garnered little attention. NASA has selected three companies to send astronauts to the International Space Station. According to a report appearing in NASA Spaceflight, the first flight under NASA’s Commercial Crew Program won’t occur until November 2017, at the earliest. As much as the program has been touted as an effort to end U.S. reliance on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, it appears that won’t be happening anytime soon.

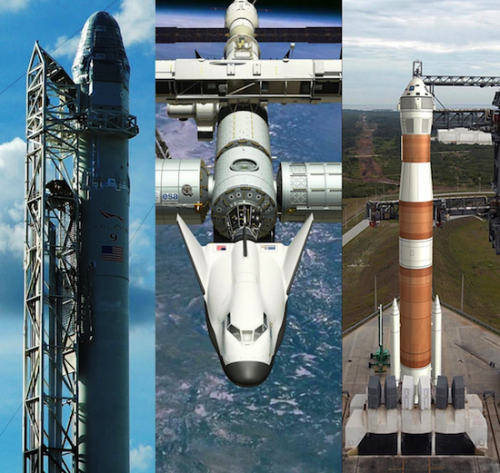

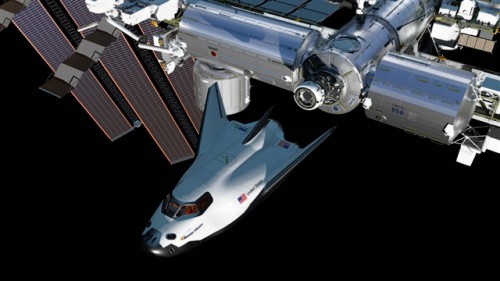

Under the Commercial Crew integrated Capability (CCiCap), NASA is attempting to have access to low-Earth orbit, primarily the International Space Station (ISS), handled by commercial companies. The three awardees that have been selected to accomplish this are Boeing’s CST-100, Sierra Nevada Corporation’s Dream Chaser space plane, and Space Exploration Technologies’ (SpaceX) Dragon spacecraft. Of the three, SpaceX can be viewed as the leader, as their offering has traveled to the ISS three times (in its unmanned configuration).

This could play into SpaceX’s favor, as NASA will likely be forced to select a single service provider in terms of crew transportation. SpaceX is unique among the competitors as it uses its own launch vehicle, the Falcon 9, to launch the Dragon. Both Boeing and Sierra Nevada have selected United Launch Alliance’s Atlas V to send their spacecraft to orbit.

According to NASA, Boeing, Sierra Nevada, and SpaceX are all accomplishing the milestones required under the CCiCap, with Boeing announcing recently that the adapter that would allow the CST-100 to be mated with ULA’s Atlas launch vehicle had completed a critical Preliminary Design Review.

As reported by NASA Spaceflight, all three companies are now working to launch their vehicles within the 2016 time frame. However, with the ongoing budget issues that the United States created by sequestration, there is a good possibility that these initial test flights are likely to slip. SpaceX has hinted that it might attempt its first test flight in 2015 using its own crew.

Once all of the commercial crew awardees complete their test flights, to be made using pilots within the companies themselves, NASA will then select a “winner.” Following afterwards will be the first official commercial crew mission, dubbed US Crew Vehicle -1 (USCV-1).

In November 2012, the Flight Planning Integration Panel (FPIP) stated that USCV-1 would be flown on Nov. 30, 2016, with a docking with the ISS slated to occur in early December.

The March update to the FPIP saw the date of the USCV-1 mission slip by a year. NASA also appears to be hedging their bets on commercial crew and doing so in a manner that is contrary to what NASA’s current leadership has touted as being one of the benefits of Commercial Crew. The premise of commercial crew was that it would allow the U.S. years of access to ISS while lowering costs. ISS operations are only planned through 2020. Since commercial crew is now slated only to grant NASA access to ISS in the last 2 years of its operations, some have raised the question of whether commercial crew is worth the billions to be spent on its development.

Since 2011, NASA astronauts have been dependent upon the Russian Soyuz spacecraft for access to ISS. After USCV-1, the Soyuz will serve in a “backup” capacity for NASA access to ISS through USCV-4, currently slated for the first half of 2019. This was decided in case that the commercial crew concept never leaves the ground. US Crewed Vehicle flights are scheduled in six-month intervals.

It should be noted that this slip has not been finalized, as the FPIP is only a planning document, although it is highly likely that this slip will take place. As reported in the NASA Spaceflight article, NASA appears to have been aware of the likelihood of this slip since this past February, with Russian media reporting that NASA is working to secure Soyuz seats through the middle of 2017.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter:@AmericaSpace

Sources:

NASA Flight Planning Integration Panel (FPIP) Document, Credit: NASAspaceflight.com

This is a bunch of bull. NASA needs to get its act together. The organization that launched men into space and to the moon within a decade now can’t even get its act together to put us in low orbit within 10 years of starting the latest project. NASA now functions as a bunch of goverment no brains, that take money and never accomplish anything of substance. All I see is more excusses, about money, NEVER do we see, “We can get the job done”. NASA is now no better than our congress, president or our country. WE HAVE LOST OUR WAY AS A NATION. very frustrated…………….

Schedule is solely a function of funding. The commercial crew folks could fly earlier if the program was funded properly. So, Congress under funds it and delay first flights, which they use to justify selecting one provider (which many in Congress are hoping to be Boeing).

This is a myopic approach because it just sends more money to the Russians and delays the real potential game-changer, the launch of private commercial Bigelow stations.

This comment was removed due to violating AmericaSpace commenting rules. Please do not promote your company in the comments section.

Asking for funding on the comment section on a artical not relating to Space Operations Inc. Stay classy Byron Russell.

I wonder if this will affect the Inspiration Mars mission. Assuming all goes well, they’re going to need a fully functional and tested space ship by Jan. 5, 2018. If this delays Dragon’s development, it might compromise the Mars mission. The other spacecraft aren’t built for deep space missions. Would Orion, another IM choice, be affected by sequestering?

The Space Launch System eats up about $3 billion a year in NASA funds. The SLS won’t even have a manned flight until 2019. Meanwhile we have the Falcon 9 taking a Dragon capsule to the ISS with a heat shield rated for a Mars return mission. The Falcon Heavy is scheduled to launch sometime this year, but most likely next year and it is built on proven technology. I have an idea of what NASA can cut, but Congress makes most of NASA’s decisions and the Senate Launch System will continue forward at the snail speed pace its been going at since it was called Constellation.

Jeffrey,

While we appreciate a spirited debate, resorting to name-calling doesn’t exactly place your position in a good light. The facts, numbers & statistics you highlighted accomplished this very well, as does the fact that you’re willing to highlight issues with commercial providers (dates slipping). I’d recommend a bit more of that & a little less of snarky names – it ruins your credibility when you do that.

Sincerely and with thanks, Jason Rhian – Editor, AmericaSpace

The Falcon 9 Heavy is to have a 200 km 28-degree LEO payload capacity of 53 mt. But it’s GTO payload capacity is a mere 12 mt, or 1 mt less than the Delta IV Heavy or Atlas V. The low-lunar-orbit (LLO) payload capacity will probably be around 10 mt.

The Dragon heat shield may be rated for beyond Earth, but the spacecraft’s size, at least in internal pressurized volume 10.0 m^3, is less than that of Apollo at 10.6 m^3. Unlike the Apollo SM, the Dragon trunk is not capable of the delta-v needed for either LLO insertion or TEI. So a good deal of work and money will be needed to human rate Dragon for BLEO, develop a new trunk, a new stage to reach the Moon, or design and build refueling capabilities, and so on.

Now let’s look at Orion/SLS. The SLS Block I will be capable of 18 mt, and the Block II of 33-38 mt, to LLO. Orion has an internal pressurized volume of over 19 m^3. The mass margins of the SLS are such that it will be able to send 2-4 times the mass to LLO that a Falcon 9 Heavy would be able to loft. And no refueling capacity needed to get to the Moon.

This comment was removed due to violating AmericaSpace commenting rules. Please do not promote your company in the comments section.

Sorry. I’m just so frustrated that the Senate approved the Space Launch System without letting other commercial companies bid for deep space destinations. We all know NASA’s current budget cannot support the exploration goals at the cost of the SLS. Sure we can build the system, but there will be nothing left for the actual missions. It is tough to see a congress make scientific decisions when so few of them are actually scientifically literate. I also don’t think I resorted to name calling when I said Senate Launch System. It was approved by the Senate.

for deep space destinations. We all know NASA’s current budget

cannot support the exploration goals at the cost of the SLS.

I don’t know that. What is your data and its source for such a statement?

When Orion development ceases, $1.2B can be reallocated to other missions. Same with the $2B annually for SLS. And ISS will stop churning through nearly $3B annually after 2020.

Are you saying that the $3.2B not spent on Orion and SLS, and $3B on ISS, for a total of $6.2B isn’t enough to get us back to the Moon and teach us how to work people beyond LEO during the 2020’s?

Anyone aware if Cape Canaveral launch pads will ever be used again for future missions?

Hi Dave,

Cape Canaveral Air For Station’s Space Launch Complexes 37, 40 & 41 – are all active pads. 41 hosted a launch last week, 37 is set to conduct a launch tomorrow. So the launch pads at Cape Canaveral conduct missions on almost (and in some cases more) a monthly basis. I hope this helps. Let me know if you would like to know anything else.

Sincerely, Jason Rhian – Editor, AmericaSpace

Thanks Jason.