Forty years ago this summer, America’s first space station—Skylab—was boosted into orbit atop the last in a generation of mighty Saturn V rockets. During launch, however, disaster struck the mission, when the station’s micrometeoroid shield and one of its electricity-generating solar arrays were torn away in the aerodynamic slipstream and the first crew were faced with enormous difficulty to turning Skylab from a barely habitable hulk into their home for a month. They returned to Earth in late June 1973, leaving a vastly improved station for the next crew. On the second mission, Skylab 3, astronauts Al Bean, Owen Garriott, and Jack Lousma were tasked to spend a record-setting 59 days in orbit, more than twice as long as had been accomplished by any previous astronaut or cosmonaut. Launched on 28 July, the mission would prove an enormous success … but that success could hardly have been imagined during Skylab 3’s first few unfortunate days.

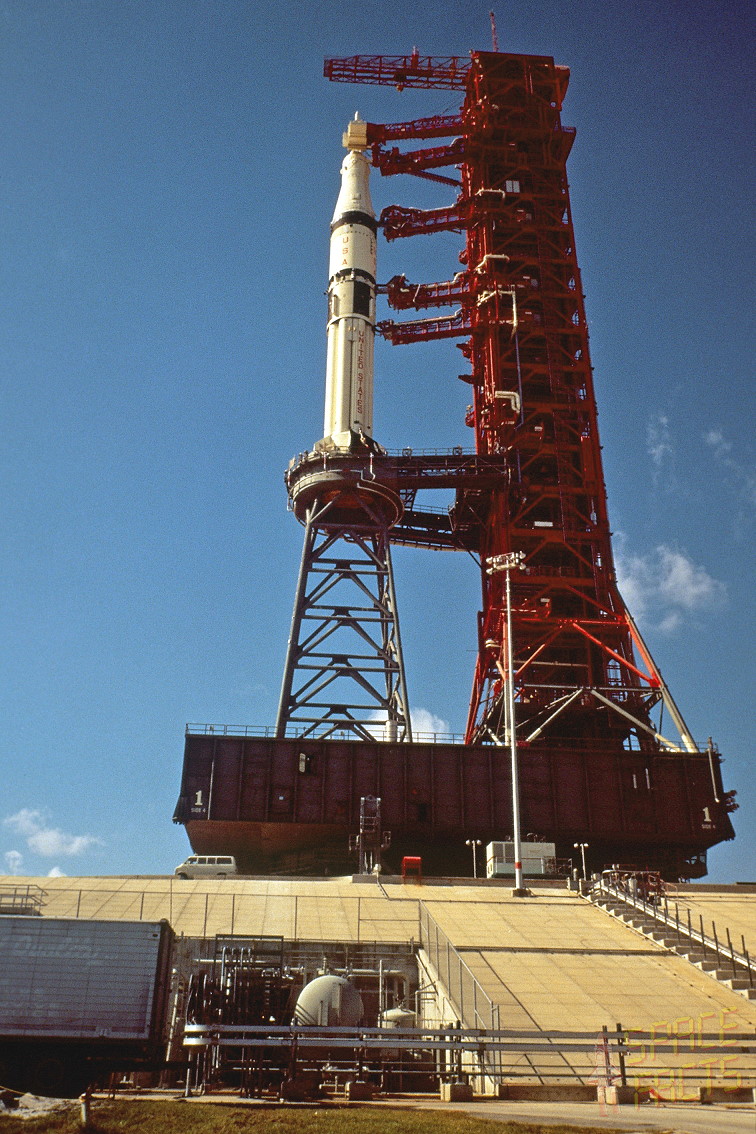

By the beginning of August, only days after launch, the crew had been hamstrung by debilitating “space sickness” and a mysterious leak from one of the four “quads” of maneuvering thrusters on their Apollo service module. The latter problem was of such severity that a rescue crew, consisting of fellow astronauts Vance Brand and Don Lind, was being readied for launch in a special five-seater craft to bring them home. Preparations at the Kennedy Space Center now shifted into high gear, with efforts to ready Pad 39B for its second Saturn IB launch in a few days. The booster to be used was the one already earmarked to transport the third Skylab crew into orbit in November.

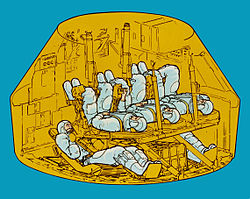

On 3 August, the processing schedule was accelerated, with technicians and engineers working around the clock to prepare the vehicle for its potential new role. The Apollo command module (known as “Skylab-Rescue” or “SL-R”) would be stripped of stowage lockers in its lower equipment bay to accommodate the three couches and “ballasted” with lead to compensate for centre-of-gravity offsets. Upon receipt of the call, a field modification kit would be installed to house a five-man crew.

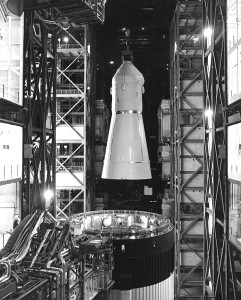

Launch of SL-R was scheduled for around 5 September, approximately three-quarters of the way through Bean, Garriott, and Lousma’s planned 59-day mission. On 10 August, less than a month ahead of this schedule, the SL-R Apollo was transferred to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) for final checkout. By necessity, this work was abbreviated and it was expected that the spacecraft could be readied for installation onto the Saturn IB and rolled out to the pad in as little as three days. Flight readiness checks would then be accomplished by 24 August, propellant loading would commence on the 27th, and launch would occur a little more than a week later. The SL-R mission was expected to last no more than five days, ending with a splashdown in the Pacific on 10 September.

Brand and Lind—together with scientist-astronaut Bill Lenoir—had already trained together since January 1972 as backups for the second and third Skylab crews. Brand would have commanded SL-R, with Lind as pilot. “I did a lot of contingency work figuring out, for example, how you could complete a rendezvous if you lost your inertial navigation unit,” Brand told the NASA oral historian, “by gauging things, using charts, using the spacecraft guidance, navigation, and control equipment in ways that it was never, ever designed to be used. I thought I could almost fly the spacecraft without thinking at the time, because I had so much exposure to Apollo training.”

However, Brand had his doubts. He had become very familiar with the schedule of launch preparations for both the spacecraft and its Saturn IB booster and felt that the “long pole” in achieving their 5 September target was getting the vehicle ready on time. “I think we would have been lucky to be off 30 days after that,” he recalled, “but we were talking about that, aiming for that.”

When the trouble with Bean, Lousma, and Garriott’s spacecraft became clearer, Brand and Lind spent most of August 1973 “figuring out how to rendezvous with them, where we would dock, outfitting our command module so that it had … padding on the aft bulkhead where people could lie … [to] get five people in the spacecraft.” In addition to stroking the struts of the couches, the number of bodies inside the command module might have posed difficulties after splashdown; if the spacecraft entered a “Stable 2” orientation (with its apex in the water) it could prove disorientating. “Vance and I had gone through some training on this out in the Gulf [of Mexico] with a real command module,” Lind recounted in his NASA oral history. For the purposes of the five-man exercise, three other astronauts, including Bill Lenoir, had joined them.

“Now, if we get in Stable 2,” Lind told Lenoir, “remember you’re on top of the vehicle and so when you unstrap, make sure you have a hold of a stanchion someplace.”

Lenoir looked at his crewmate, incredulously, with an expression that read: “Lind, how dumb do you think I am?”

“Well,” Lind told the oral historian, “we got in Stable 2. The radio called for [Lenoir] to unstrap. It was hard to realise that you were now strapped [to] the ceiling, because it was bouncing around in the water. He released his seatbelt and, wham! Then he looked at me like ‘If you say one word, I’ll kill you!’”

Other considerations included which experiments the rescue mission could bring home, in view of the limited stowage volume aboard SL-R. Brand assigned Lind the job of “cargo master” to make these decisions, based on weight and center-of-gravity concerns. “I had to inventory all the possible decisions to maximise the scientific return with the limited capability we had to return all that data,” Lind recounted. According to contemporary NASA documents, in addition to the safe return of both crews to Earth, the main objectives were to bring back “selected” experiment data, to perform a diagnosis of the failure of the original Apollo craft, and to configure Skylab for a revisit. In terms of samples to be returned to Earth, the frozen urine specimens and dried feces were of primary interest from a medical standpoint. Film from the Earth resources instrumentation and Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) were also critical.

Aside from the rescue itself, the men worked a number of what Brand called “unorthodox” procedures, bypassing the service module and re-entering with only the command module’s thrusters. The mood was lightened when further investigation confirmed that none of the RCS oxidizer batches were contaminated and had not contributed to the leak. It also appeared that Quads A and C were unaffected and a subsequent investigation would attribute the failure to undetected loose fittings in oxidiser lines.

Throughout those heady days in August 1973, Brand and Lind developed a number of work-around procedures. One of these enabled Bean to achieve translational capability and complete the de-orbit burn with only the command module’s attitude thrusters. “We were so clever as the backup crew,” said Lind, “that we worked ourselves out of a flight! You really didn’t want to have to go rescue them.” Their workaround, together with the engineering expertise of others on the ground and of the crew in orbit, ensured that Bean’s crew could complete their flight. Rather than making a two-stage SPS burn for re-entry, it was decided that the men would perform a single burn and that if there were no more leaks, the rescue mission could be stood down.

In a strange way, it was disappointing, particularly for Lind, who had long desired a Skylab mission, but he knew that both Lousma and Bill Pogue were “depressingly healthy” and there would be essentially no chance that he would be called upon to take their place on a prime crew. Even the old backup crewman’s technique of straw dolls and long pins, it seemed, would have little effect. Flying the short SL-R mission was his last chance to see Skylab up close and in orbit.

As the situation began to improve, with the workarounds and the relief that the leaks did not represent a systemic flaw and the oxidiser batches were not contaminated, plans changed quickly. The decision to remove SL-R from consideration changed everything overnight. On 14 August, only days after the transfer of the spacecraft to the VAB, NASA announced that the Saturn IB was now being retasked for launch no earlier than 25 September; effectively, the agency was removing it from immediate duty as a rescue craft, since Bean, Garriott, and Lousma were already scheduled to land at around that time.

This decision ties in with Lousma’s assertion that “after about ten days or so” into the crisis, the crew was advised that they could stay aboard Skylab and continue their mission. The decision underlined a growing confidence that the crew would most likely be able to complete the planned 59-day flight. On that same day, 14 August, the Saturn—now reassigned to its original purpose of transporting the final Skylab crew—was rolled to Pad 39B to begin its own launch preparations. Nevertheless, upon the completion of hypergolic propellant loading aboard the booster on 10 September, the vehicle remained in a “Launch Minus Nine Days” stand-by status until Bean’s crew were safely back on Earth.

A few months later, in January 1974, the SL-R command and service module was transferred to the VAB, where it later saw service as a backup vehicle for the Apollo-Soyuz mission. After that, for many years, it resided in the Kennedy Space Center’s visitor area and, in 2007, was “commandeered” by NASA to aid studies of a similar rescue capability for the Orion spacecraft. It is interesting and appropriate that lessons from the past continue to be learned for the future and, indeed, the post-Columbia practice of having partial crews on stand-by for a rescue is by no means a new one: it had been pioneered, worked out, and perfected all those years ago.

For Brand and Lind, losing the chance to fly the rescue mission as a direct result of the thoroughness of their own work was a bittersweet experience. “You really feel not just a professional obligation, but also a personal obligation,” Lind remembered, “to the fellows on the crew that you know so well to do that job very well. We did the best job we could and were able to convince management that we had enough redundancy to bring the guys home with the quad problems.” For his part, Brand was philosophical. Commanding the world’s first-ever space rescue mission would have been an intensely rewarding achievement for the rest of his life.

Today—exactly four decades to the week since those momentous plans were being laid—we should take a moment to express relief: for although it would have been “interesting” to see Brand and Lind fly their mission, we should be thankful that they did not have to.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will continue the focus on Skylab’s 40th anniversary, by exploring the scientific successes of the three missions.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter:@AmericaSpace

Ben – thank you for a most interesting series of articles on Skylab, particularly with respect to the rescue mission situation. You have provided excellent details about this scenario that I was unaware for these past four decades. We should be deeply impressed and reminded once again as to the total preparation and dedication of the astronauts and the ground crew in making Skylab the success it was. We salute the heroes of Apollo but let ‘s never forget the important contributions that Brand and Lind made – they are heroes indeed!