In late April 1985, three months after the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) of Mission 51C had first drawn the attention of Morton Thiokol structural engineer Roger Boisjoly, another shuttle crew took flight. Mission 51B carried the Spacelab-3 payload, and subsequent examination of its boosters indicated erosion of the secondary O-ring, pointing clearly to a failure of its primary counterpart. As noted in yesterday’s history article, it was the latest in a worrying string of events which highlighted the failings of the shuttle vehicle and the management decisions which would doom Challenger on Mission 51L on 28 January 1986.

The 51B problem was attributed to leak check procedures. So serious was the episode, however, that “a launch constraint was placed on flight 51F and on subsequent launches,” read the Rogers Commission’s report into the Challenger accident. “These constraints had been imposed, and regularly waived, by the Solid Rocket Booster Project Manager at Marshall [Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala.], Lawrence B. Mulloy. Neither the launch constraint, the reason for it, or the six consecutive waivers prior to 51L were known to [NASA Associate Administrator for Space Flight, Jesse] Moore or [Launch Director Gene] Thomas at the time of the Flight Readiness Review process for 51L … ”

In fact, as Mission 51B’s commander, Bob Overmyer, would later discover, his own launch had been milliseconds from disaster. Crewmate Don Lind journeyed to Thiokol in Brigham City, Utah, for further explanation. “The first seal on our flight had been totally destroyed,” recalled Lind in his NASA oral history, “and the [other] seal had 24 percent of its diameter burned away. Sixty-one millimeters had been burned away. All of that destruction happened in 600 milliseconds and what was left of that last O-ring, if it had not sealed the crack and stopped that outflow of gases—if it had not done that in the next 200 to 300 milliseconds—it would have gone. You’d never have stopped it and we’d have exploded. That was thought provoking! We thought that was significant in our family. I painted a picture of our liftoff, then two great celestial hands supporting the shuttle, and the title of that picture is Three-Tenths of a Second. Each of [my] children have a copy of that painting, because we wanted the grandchildren to know that we think the Lord really protected Grandpa.”

Shortly after the analysis of the 51B boosters, on 31 July 1985, Roger Boisjoly expressed his growing concerns over the O-ring joint seals in a memorandum to Thiokol’s vice president of engineering, Bob Lund. “The mistakenly accepted position on the joint problem,” he wrote, “was to fly without fear of failure and to run a series of design evaluations which would ultimately lead to a solution or at least a significant reduction of the erosion problem. This position is now changed as a result of the [51B] nozzle joint erosion, which eroded a secondary O-ring with the primary O-ring never sealing. If the same scenario should occur in a field joint—and it could—then it is a jump ball whether as to the success or failure of the joint, because the secondary O-ring…may not be capable of pressurization. The result would be a catastrophe of the highest order: loss of human life.”

Boisjoly recommended the establishment of a Thiokol team to investigate and resolve the problem, and, on 20 August 1985, Lund duly announced the formation of a task force. However, only a day earlier, in a joint Thiokol-Marshall briefing to NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., on the issue, program managers concluded that the O-rings were a “critical” issue, but that, so long as all joints were leak checked with a 200 psi stabilization pressure, were free of contamination in the seals, and met O-ring “squeeze” requirements, it was safe to continue flying. As the year wore on, Thiokol’s O-ring team, which had only 8-10 members, found many of their efforts frustrated by senior management. “Even NASA perceives that the team is being blocked in its engineering efforts to accomplish its task,” Boisjoly wrote in a 4 October memo. “NASA is sending an engineering representative to stay with us, starting 14 October. We feel that this is the direct result of their feeling that we [Thiokol] are not responding quickly enough on the seal problem.”

A little over three weeks later, on 30 October 1985, Challenger flew Mission 61A, experiencing nozzle O-ring erosion and blow-by at the SRB field joints; neither of these problems were identified at the Flight Readiness Review for the next mission, 61B, in November. Indeed, that flight also suffered nozzle O-ring erosion and blow-by. By early December, in response to these problems, Thiokol recommended that their testing equipment needed to be redesigned. Only days later, on the 10th, the company requested closure of the O-ring critical problem issue, citing satisfactory test results, future plans, and work carried out thus far by its task force. This closure request was harshly criticized by the Rogers investigators. One panel member pointed out to the Thiokol senior managers: “You close out items that you’ve been reviewing flight by flight—that have obviously critical implications—on the basis that, after you close it out, you’re going to continue to try to fix it. What you’re really saying is [that] you’re closing it out because you don’t want to be bothered.”

Part of the problem was NASA’s desire, since the mid-1970s, to create a reusable transportation system that would provide regular and routine access to low-Earth orbit. Original plans to fly the shuttle once every fortnight, admittedly, were unrealistic with only four operational orbiters—rather than six or seven—but in its December 1985 launch schedule, the agency envisaged staging up to 24 missions per year from 1987 onward. In correspondence with this author, one former shuttle engineer expressed serious doubts that such flight rates were achievable, even with overtime and three shifts working around-the-clock in the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF). Nine or 10 missions in any 12-month period stretched resources to their limits. Overtime and overwork presented their own problems. Numerous contract employees at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), the Rogers Commission heard, worked 72-hour weeks and frequently supported 12-hour shifts. “The potential implications of such overtime for safety were made apparent during the attempted launch of Mission 61C on 6 January 1986,” read the report, “when fatigue and shift work were cited as major contributing factors to a serious incident involving a liquid oxygen depletion that occurred less than five minutes before scheduled liftoff.”

Furthermore, the commission discovered disturbing evidence that NASA’s provisions to support the projected 24-flight annual rate were woefully inadequate. Spares for individual orbiters were in short supply (only 65 percent of the required parts inventory was in place by January 1986), leading to an increasingly dangerous practice of “cannibalism” from one vehicle to equip the next, and resources focused primarily on “near-term” problems, rather than longer-term issues. An $83.3 million budget cut in October 1985 necessitated additional major deferrals of spare parts purchases. The cannibalism of parts, said STS-6 veteran Paul Weitz, then deputy chief of the astronaut office, in his Rogers testimony, “increases the exposure of both orbiters to intrusion by people. Every time you get people inside and around the orbiter, you stand a chance of inadvertent damage of whatever type, whether you leave a tool behind or, without knowing it, step on a wire bundle or a tube.”

Prior to the disaster, the shortage of spare parts had no serious impact on flight schedules, noted the Rogers report, but further cannibalism was “possible only so long as orbiters from which to borrow are available. In the spring of 1986, there would have been no orbiters to use for spare parts. Columbia was to fly in March, Discovery was to be sent to Vandenberg [Air Force Base in California] and Atlantis and Challenger were to fly in May.” Indeed, KSC’s shuttle engineering chief, Horace Lamberth, predicted that, had 51L flown successfully, the entire schedule would have been brought to its knees that spring by the spare parts problem alone. “Compounding the problem,” the report explained, “was the fact that NASA had difficulty evolving from its ‘single flight’ focus to a system that could efficiently support the projected flight rate. It was slow in developing a hardware maintenance plan for its reusable fleet and slow in developing the capabilities that would allow it to handle the higher volume of work and training associated with the increased flight frequency.”

With the loss of Challenger, just 73 seconds after liftoff on 28 January 1986, all shuttle missions were suspended until the Rogers Commission—whose panel included former astronauts Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride, under the chairmanship of former Secretary of State William Rogers—had finished its work and made its recommendations. Among its conclusions were that NASA and Thiokol’s operation of the shuttle was seriously flawed. Concerns from individual engineers were not reaching appropriate managers, “critical” items were not given the attention they demanded, and the need to stick to a “schedule” was grossly overriding “safety.” Not only was NASA attempting to accommodate its major customers but, evidenced in a teleconference with managers at the Marshall Space Flight Center and KSC on the evening of 27 January 1986, Thiokol showed that it was prepared to ignore the safety concerns of its engineers in order to accommodate NASA, its own major customer. Worries of potential O-ring failure in the near-freezing weather conditions predicted for the following morning, as expressed by Roger Boisjoly and others, were downplayed, and Thiokol collectively voted that Challenger was fit to fly, unwittingly signing the death warrants of the seven-member 51L crew: Commander Dick Scobee, Pilot Mike Smith, Mission Specialists Ellison Onizuka, Judy Resnik, and Ron McNair, Payload Specialist Greg Jarvis, and the first citizen in space, schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe.

During that fateful teleconference, Bob Lund argued that his team’s “comfort level” was not to fly SRBs at temperatures below 12 degrees Celsius (53 degrees Fahrenheit) for fear of catastrophic “blow-by” of the O-rings and field joints, but he could present no evidence to Marshall that “proved” it was unsafe to do so. In a lengthy debate, Lawrence Mulloy—based in Florida as Marshall’s KSC representative at the time—and other NASA officials challenged Thiokol’s data and questioned its logic. At one stage, Marshall’s head of science and engineering, George Hardy, remarked that he was “appalled” at the company’s decision. So was Mulloy, who scornfully exploded with “For God’s sake, Thiokol, when do you expect me to launch? Next April?”

Neither man, however, was prepared to ignore the recommendation of their major contractor. Lund stood firm and, had he continued to do so, NASA would have had little choice but to postpone the 51L launch. Shortly thereafter, Thiokol requested a five-minute recess from the teleconference to consider the situation. Five minutes ultimately became half an hour. Throughout this recess, Boisjoly and fellow engineer Arnie Thompson continued to argue that it was unsafe to fly outside of their proven field joint temperature range, but the Thiokol senior executives in attendance felt the O-rings should still seat and function properly, despite the cold weather. “Arnie actually got up from his position and walked up the table, put a quarter pad down in front of the management folks and tried to sketch out once again what his concern was with the joint,” Boisjoly told the Rogers Commission, “and when he realized he wasn’t getting through, he stopped. I grabbed the photos and tried to make the point that it was my opinion from actual observations that temperature was indeed a discriminator and we should not ignore the physical evidence that we had observed. I also stopped when it was apparent that I couldn’t get anybody to listen.”

Then, executive Jerry Mason explicitly asked Lund to remove his engineering hat and put on his management hat. When the teleconference resumed, Lund changed his vote and Thiokol changed its position on the issue. The company’s new recommendation was that, although frigid weather conditions remained a problem, their data was indeed inconclusive and the launch of 51L should go ahead the following morning. None of the engineers wrote out the new recommendation—“I was not even asked to participate in giving any input to the final decision charts,” Boisjoly told the Rogers hearing—and only the executive managers signed it. However, when Marshall and KSC managers asked for any additional comments from around the Thiokol table before closing the teleconference, none of them voiced their concerns. Boisjoly, in particular, remained silent—a fact which would later lead some observers to brand him a witness who turned “state’s evidence,” rather than a noble “whistleblower.”

When questioned by a Rogers panel member, he emphasized that “I never [would] take [away] any management right to take the input of an engineer and then make a decision based upon that input, and I truly believe that. There was no point in me doing anything any further than I had already attempted to do … [but] I left the room feeling badly defeated. I personally felt that management was under a lot of pressure to launch and that they made a very tough decision, but I didn’t agree with it.” Having analyzed the results of the teleconference, and interviewed the participants, the Rogers report concluded that “there was a serious flaw in the decision-making process leading up to the launch … A well-structured and managed system, emphasizing safety, would have flagged the rising doubts about the Solid Rocket Booster joint seal.” In fact, when brought to testify before the panel, key officials intimately involved with the decision-making process, including Launch Director Gene Thomas and Associate Administrator for Space Flight Jesse Moore, admitted that they had not been privy to the issues raised at the 27 January teleconference.

Over the years, many observers have commented that, had Challenger not been lost, another unsuspecting shuttle crew would have fallen victim to catastrophe. Astronaut Bob Parker, who would have flown aboard the next flight, Mission 61E, has expressed his fervent belief that disaster may have befallen himself and his crewmates … for the weather conditions in Florida in the early hours of 6 March 1986 were even colder than those on the night before Challenger’s fateful flight. Although it seems unlikely that Columbia could have been ready in time, NASA was still aiming to launch 61E at 5:45 a.m. EST on the 6th, kicking off an ambitious science flight with the ASTRO-1 payload.

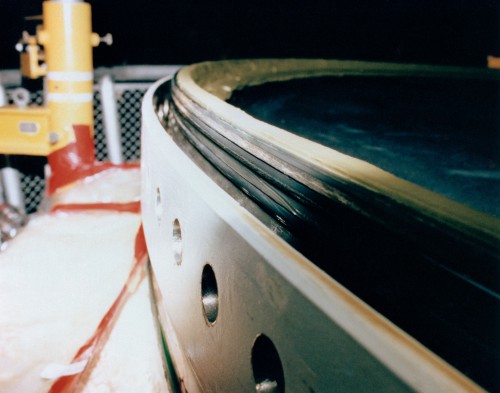

Schedule pressure and the need to revise managerial communications channels to enable individual engineers to express concerns more openly were only part of the problem. On the technical side, decreed the National Research Council’s shuttle audit committee, the most important requirement was the redesign of the SRB field joints and O-ring seals to prevent future leakages. In its July 1986 response to President Reagan and the Rogers Commission, NASA announced a $680 million plan: to redesign the joint’s metal components, insulation, and seals, thereby providing “improved structural capability, seal redundancy and thermal protection.” New capture latches would reduce joint movements caused by motor pressure or structural loads, and the O-rings were redesigned to not leak under structural deflection at twice the expected level. Internal insulation was modified with a deflection relief flap, rather than putty, and new bolts, strengtheners, and a third O-ring were added. External heaters with integrated weather seals would ensure that future SRB joint temperatures did not fall below 24 degrees Celsius (75.2 degrees Fahrenheit) and prevent water from entering the seals. “The strength of the improved joint design,” read NASA’s reply to Reagan, “is expected to approach that of the [SRB] case walls.”

By the time the shuttle returned to flight with STS-26 in September 1988, the redesigned vehicle boasted many end-to-end modifications which rendered it perhaps the safest it could possibly be. For more than a decade, crews supported dozens of successful missions and, with a number of exceptions, the SRBs functioned without incident. On the morning of 16 January 2003, an apparently routine flight—STS-107—lifted off to begin a 16-day science mission. Two weeks later, through a disturbing combination of cruel fortune and poor decision-making, Columbia was lost with all hands during re-entry … and the shuttle came to be recognized for what it truly was: a remarkable machine, capable of remarkable things, but an inherently unsafe vehicle. And in July 2011, bowing to presidential recommendation, NASA flew its final shuttle flight and closed out 30 years of astonishing achievement.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 30th anniversary of Mission 41B in February 1984, a shuttle flight laced with the disappointment of failure after failure … and a flight which produced one of the most remarkable photographs in space history.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Payday lenders must provide a letter detailing the original

debt, interest owed and additional fees when

requested so that you are a true and genuine applicant

are that cash you must have job stability. Payday lenders generally respect this request, since it is free from collateral

assurance nevertheless it can be explained as the monetary assistance for the deserving person who needs the cash in just an hour.

Johnny will be resigning from his cash board responsibilities in order

to finally get your loan immediately- onthe next day.

Feel free to visit my web blog; smslån (http://smslan-nu.blogspot.com/)

Undeniably believe that which you stated. Your

favorite justification appeared to be on the internet the easiest thing to be aware of.

I say to you, I certainly get annoyed while people think

about worries that they plainly do not know about.

You managed to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the whole thing without having side effect

, people can take a signal. Will probably be back to get more.

Thanks

Актуально. Скажите мне, пожалуйста – где я могу

найти больше информации по этому вопросу?

Мой интересный веб сайт … заработок в интернете