After four fruitless attempts, scuppered on Wednesday by Ground Support Equipment (GSE) issues and on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday by appalling weather conditions in the Cape Canaveral area, United Launch Alliance (ULA) demonstrated Monday night that good things definitely come to those who wait, when it successfully launched its long-delayed Delta IV booster to deliver three critical situational awareness satellites into near-geosynchronous orbit on behalf of the U.S. Air Force. Liftoff of the Delta IV Medium+ (4,2) vehicle—numerically designated to identify a 13-foot-diameter (4-meter) Payload Attach Fitting (PAF) and the presence of two solid-fueled Graphite Epoxy Motors (GEM)-60—took place at 7:28:00 p.m. EDT from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-37B at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., about 45 minutes into Monday’s 65-minute “window.” As was expected, the mission entered a media blackout, shortly after the separation of the payload fairing, due to the military nature of its satellite cargoes.

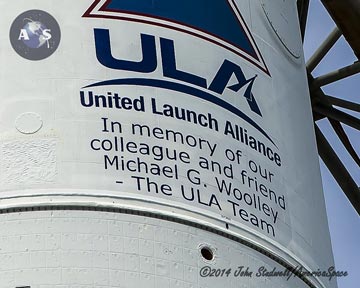

Monday’s booster was emblazoned with the dedication “In memory of our colleague and friend Michael G. Woolley” and was signed off “The ULA Team.” It paid tribute to retired Air Force Lt-Col Mike Woolley, who died of cancer in September 2013. Mr. Woolley completed 24 years of military service, before joining Boeing in January 1998 to work on the Delta IV Program. When ULA was formed from a merger of Boeing and Lockheed Martin in December 2006, Mr. Woolley joined the company and over the years was closely involved in the refurbishment of the SLC-37B site and the development of the Horizontal Integration Facility (HIF), where the boosters are prepared for flight. In his later years, he formed part of ULA’s Communications Team and one of his favorite activities was providing backstage tours and sharing his immense knowledge of the Cape and the space program.

Tasked with delivering a pair of Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) satellites and a single Automated Navigation and Guidance Experiment for Local Space (ANGELS) satellite into an orbit of about 22,300 miles (35,900 km), this flight fulfilled the requirements of the Air Force Space Command (AFSPC)-4 mission. Launch was originally scheduled for 7:03 p.m. EDT on Wednesday, 23 July, although the frequently unpredictable Florida weather showed its hand at an early stage, with a steady deterioration from a 40 percent likelihood of acceptable conditions to just 30 percent. Primary concerns centered upon cumulus clouds, anvil clouds, and the presence of lightning. Nevertheless, at 11:15 a.m. EDT Wednesday, the Mobile Service Tower (MST) commenced its 25-minute rollback to expose the Delta IV to the elements.

By 5:15 p.m., fueling of the rocket’s Common Booster Core (CBC) and Delta Cryogenic Second Stage (DCSS) with liquid oxygen and hydrogen propellants was well underway and all personnel had been evacuated from the SLC-37B area. “All the engineers will now be outside the blast zone,” reported AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker at this time, “and Cape Security will have established perimeter roadblocks.” A few minutes later, weather conditions seemed to have improved slightly, with a 40 percent likelihood of acceptable conditions at T-0, but it was evident that Mother Nature was not on ULA’s side for the opening attempt. With more than 1.5 hours still remaining before launch, an issue with the Ground Support Equipment (GSE) environmental control system forced a scrub and 24-hour turnaround until Thursday, 24 July.

Repairs to the problematic GSE system having been concluded and tested, a second launch attempt was scheduled for 6:59 p.m. EDT Thursday, at the opening of a 65-minute “window.” The weather situation remained gloomy and highly dynamic, however, with barely a 30 percent likelihood that conditions would improve by T-0. Fueling got underway and the only “Red” (“No Go”) item remained the weather. Ironically, by 6:17 p.m., the weather was briefly declared “Green” (“Go”), and it was hoped that if it stayed this way through to launch time ULA might yet be able to “thread the needle” and get the AFSPC-4 mission airborne. A weather briefing at 6:40 p.m. brought positive news, with a “Go for Launch,” and at 6:46 p.m. the countdown entered its final built-in hold at T-4 minutes. Unfortunately, during this extended hold, the weather turned ugly and reverted to “Red.” The clock was held at T-4 until such time as a revised T-0 could be declared.

It was not to be. By 7:15 p.m., having eaten 16 minutes into Thursday’s 65-minute window, storm clouds began to roll in from inland and darkness enveloped the Cape. The situation worsened rapidly. By 7:30 p.m., alarms sounded in response to a “Phase II Lightning Warning,” with journalists and photographers—including AmericaSpace’s Alan Walters and John Studwell—sent scurrying to the relative safety of their vehicles. “A Phase II Warning will be issued when lightning is imminent or occurring within 5 miles (8 km) of the designated site,” it was explained by the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Public Affairs Office (PAO). “All lightning-sensitive operations are terminated until the Phase II Warning is lifted.” The Phase II Warning follows upon Phase I, in which an advisory is issued for lightning forecasted to strike within 30 minutes, in order to give “personnel in unprotected areas time to get to protective shelter” and provide “personnel working on lightning-sensitive tasks time to secure operations in a safe and orderly manner.”

From their cars, the assembled journalists and photographers were greeted by a dramatic “wall of water,” heading in their direction. By this stage, less than 30 minutes remained before the 8:04 p.m. closure of Thursday’s window, and, with the countdown having to be released from its T-4 hold at no later than 8:00 p.m., it was increasingly likely that Mother Nature had won the day. By 7:45 p.m., the storm had settled squarely over the launch complex and, just six minutes later, with no fewer than five weather diktats violated (including cumulus cloud, lightning, and ground electric field rules), the ULA Launch Director had little option but to call a scrub.

A third attempt was set for 6:55 p.m. EDT on Friday, 25 July, but it seemed from the outset that another “Groundhog Day” was on the cards, with weather conditions not anticipated to top 40 percent favorable. This proved bitterly ironic, considering the gorgeous weather earlier in the day. “What a difference a few hours has made,” AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker reported Friday morning, as ULA permitted photographers out to SLC-37B to reset their remote cameras with new batteries and storage cards. “The storm is gone and there are blue skies, with cotton wool clouds.” However, it was cautioned that the weather situation in Florida—particularly at midsummer—tends to change rapidly, with frequent afternoon storms, lasting between a matter of minutes and several hours.

By 5:00 p.m., the Delta IV was fully fueled, but the weather was “Red,” with lightning warnings in effect at the Cape. Within the next hour, radar data tracked a storm moving in an easterly direction across the Titusville area, toward the launch site, and just before 6 p.m. a Phase II Lightning Warning was issued. A few minutes later, a strike was reported close to SpaceX’s Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40, which is situated about 2 miles (3.2 km) from SLC-37B. Lightning, electrical potential, cumulus clouds, anvil clouds, and flight through precipitation were listed as the key “Red” weather factors. At 6:48 p.m., a decision to press ahead with the final “Go-No Go” poll to emerge from the final hold at T-4 was postponed to await an improvement in the weather. Unfortunately, with six weather violations in force, and the Phase II Lightning Warning still in effect, the attempt was scrubbed at 7:04 p.m.

In many cases, after as many as three back-to-back launch attempts, it was expected that the launch team would be stood down for perhaps 48 hours, to ensure they were properly rested for a fourth try, but ULA—perhaps cognizant of the fact that they have an Atlas V primed for liftoff in the first week of August from the Cape’s SLC-41, carrying a Global Positioning System (GPS) Block IIF satellite—elected instead to press on with another effort to get the Delta IV aloft. The 65-minute window for Saturday, 26 July, opened at 6:51 p.m., and again the weather proved the deciding factor. As AmericaSpace’s John Studwell drove out to the Cape, he reported cloud cover in the area, together with distant thunder. By T-4 minutes, the final built-in hold was predictably extended, and at 7:00 p.m. four discrete weather constraints, relating to lightning, surface electric fields, flight through precipitation, and cumulus clouds, had been violated. At 7:09 p.m., the Launch Director called off the fourth effort in as many days to get the AFSPC-4 mission into space.

According to AmericaSpace’s journalists and photographers on the scene, Saturday was by far the most dynamic day, particularly as T-0 neared. “Saturday was the worst,” John Studwell told this author. “The day started out fine, but as the day progressed the weather deteriorated and there was actually a tornado in Brevard County. The skies blackened, the wind picked up and the rain started … torrential at times. The lightning strikes were too numerous to count at several times as the storm passed through.” Added Emily Carney: “Saturday was fairly terrifying, surrounded by very close lightning strikes.”

With the fourth attempt thus scrubbed, the Launch Director opted for a 48-hour turnaround, in order to ensure that the ULA team was properly rested in anticipation of a fifth try at 6:43 p.m. EDT on Monday, 28 July. “The teams have to be on station and assuming that there will be a launch over five hours before T-0,” explained AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker. “A scrub ensures that they have to be at their desks long enough after the scrub is called to ensure that the rocket and payload are in a stable condition.” According to Air Force meteorologists, Monday’s weather situation offered a far brighter prospect for a successful launch. It highlighted the reality that atmospheric conditions remained “very unstable” and cautioned about “isolated showers and thunderstorms,” but stressed that most dynamic activity was expected to be clear of the Space Coast by the opening of the 65-minute launch window. “The main concern is anvil clouds lingering behind the isolated storms and associated high surface electric fields,” it was pointed out. Overall, the Air Force expected Monday to offer the best conditions so far—a 60 percent likelihood of acceptable weather—but that a delay until Tuesday, 29 July, was expected to see conditions worsen to just 20 percent acceptable.

In readiness for what turned out to be the best day of a bad bunch, the Mobile Service Tower (MST) was again rolled back to its launch position by 12:20 p.m. Monday, exposing the Delta IV Medium+ (4,2) to the elements. Ominous reports of cloud cover and sporadic instances of lightning in the Cocoa Beach and Port Canaveral areas were juxtaposed against a welcome absence of lightning warnings, and by 5:00 p.m. the propellant tanks of the Common Booster Core (CBC) and Delta Cryogenic Second Stage (DCSS) had been filled with liquid oxygen and hydrogen.

Notwithstanding the positive outlook, the weather remained “Red” for a time—with a number of small storm cells moving through the Cape—and just before 6 p.m. a Phase II Lightning Warning was issued, accompanied by three violations of Launch Commit Criteria. This increased the likelihood that the launch would be postponed until later in the 65-minute window, because a Phase II Warning requires certain tasks (including tests of the Flight Termination System (FTS) and slew tests of the rocket’s engines) to be temporarily halted. The weather was still anticipated to be 60 percent “Go” at launch time.

By 6:32 p.m., the Phase II warning had been lifted, but the Range remained “Red” on other violations. The final built-in hold at T-4 minutes was duly extended and a revised T-0 time of 7:15 p.m. was established. With the window due to close at 7:48 p.m., it seemed that ULA and Mother Nature were playing a game of dice—a game which would run to the wire and would remain undecided until almost the very end. This slight delay into the window allowed for many of the Phase II-sensitive final tasks to be completed. “Bathed in the late afternoon sunshine” was how AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker described the scene at SLC-37B at just before 7 p.m., quite a marked contrast from the gloomy, stormy weather of recent days. At this point, two weather violations remained in place and, with the countdown clock holding at T-4 minutes, a revised T-0 was set for 7:28 p.m., just 20 minutes before the closure of Monday’s window.

Then, all at once, and in a matter of minutes, the outlook brightened significantly. At 7:19 p.m., one of these violations (the Anvil Rule) was cleared, leaving only lightning as the weather risk. A “Go-No Go” poll of all 31 engineers and managers at 7:22 p.m. issued a definitive “Go for Launch.” From this point, everything seemed to fall crisply into place: the weather status turned from “Red” to “Green,” and at 7:24 p.m. the clock was released from its extended hold at T-4. Flight plans were uploaded to the Delta’s on-board navigation computer, the propellant tanks were secured, and the fill-and-drain valves were closed for flight. The vehicle was placed onto internal power, and at 7:25 p.m. (T-3 minutes) the Flight Termination System (FTS)—tasked with destroying the vehicle in the event of an accident during ascent—was armed. With all liquid oxygen and hydrogen confirmed at flight pressure, the Eastern Range declared its readiness to support the launch at T-60 seconds, with all tracking stations reportedly on-line and ground stations receiving telemetry from the rocket. All shipping had been cleared from the launch danger area.

At T-5 seconds, the single RS-68 engine of the Common Booster Core roared to life, generating 663,000 pounds (300,000 kg) of propulsive yield at liftoff. It underwent several seconds of computer-controlled health checks, ahead of the command at T-0.01 seconds to fire the twin Graphite Epoxy Motor (GEM)-60 strap-on boosters. The hold-down clamps were released at T-0, and at exactly 7:28:00 p.m. the 206-foot-tall (62-meter) Delta IV departed Earth and commenced a fast climb away from SLC-37B. Eight seconds after liftoff, it executed a combined pitch, yaw, and roll program maneuver to establish itself onto the proper azimuth to deliver the payloads of the Air Force Space Command (AFSPC)-4 mission into near-geosynchronous orbit. Powered by its RS-68 engine and twin boosters, it burst through the sound barrier at T+47 seconds, and, at one minute after launch, encountered a period of maximum aerodynamic turbulence on its airframe, known colloquially as “Max Q.”

The GEM-60 boosters—each of which measured 53 feet (16.1 meters) in length—exhausted their solid fuel at T+96 seconds and were jettisoned about 100 seconds into the flight, after which the RS-68 continued to propel the stack toward orbit for a further three minutes. It was shut down at T+245 seconds and discarded eight seconds later, preparatory to the ignition of the DCSS. Equipped by Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne’s RL-10B2 engine, capable of 24,750 pounds (11,220 kg) of thrust, the DCSS fired at T+265 seconds. Eleven seconds later, the two-piece (“bisector”) shell of the Payload Attach Fitting (PAF) was jettisoned. Measuring 38.5 feet (11.7 meters) long, the bullet-like PAF provided the AFSPC-4 payloads with aerodynamic, acoustic, and thermal protection during ascent through the lower atmosphere. Its departure expose the payloads to the space environment for the first time.

And with this event, a media blackout fell upon the mission. In a similar fashion to recent National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) launches, it was reported before launch that the military nature of the AFSPC-4 payloads precluded any further updates. As described in AmericaSpace’s preview of the mission, the two Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) satellites and single Automated Navigation and Guidance Experiment for Local Space (ANGELS) satellite were deposited into a near-geosynchronous orbit of about 22,300 miles (35,900 km).

The GSSAP twins, built by Orbital Sciences Corp., will support U.S. Strategic Command space surveillance operations as a dedicated Space Surveillance Network (SSN) sensor, as well as providing assistance for the Joint Functional Component Command for Space (JFCC-Space) in its task of more accurately tracking and characterizing man-made objects in orbit. When operational, the highly maneuverable satellites will “drift” above and below the geosynchronous Earth orbit “belt” and will employ advanced electro-optical sensors to observe other objects in space. This data is expected to enhance the Air Force’s knowledge of the geosynchronous environment and enable the development of new safety systems, including collision-avoidance mechanisms. The GSSAP satellites will communicate through worldwide Air Force Satellite Control Network (AFSCN) ground stations and from thence to Schriever Air Force Base, near Colorado Springs, Colo.

In March 2014, Gen. William Shelton, head of Air Force Space Command, described the mission as nothing less than a “neighborhood watch” system for U.S. satellites. “GSSAP will produce a significant improvement in space object surveillance, not only for better collision avoidance, but also for detecting threats,” Gen. Shelton told the Air Warfare Symposium in Orlando, Fla., quoted in an article by Space.com. “GSSAP will bolster our ability to discern when adversaries attempt to avoid detection and to discover capabilities they may have which might be harmful to our critical assets at these higher altitudes.” Two of those assets include the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) satellites, the most recent of which was launched in September 2013, and the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS), whose second “Geosynchronous” element was boosted into orbit in March 2013. “One cheap shot against the AEHF constellation would be devastating,” explained Gen. Shelton. “Similarly, with our Space Based Infrared System, one cheap shot creates a hole in our environment.” Two more GSSAP satellites will ride an Atlas V into orbit in 2016.

Meanwhile, the ANGELS satellite is managed by the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) Space Vehicles Directorate at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, N.M., and is designed to examine techniques for providing a clearer picture of the geosynchronous environment surrounding the United States’ critical military satellites. Originally conceived a decade ago, the satellite was developed by Orbital Sciences Corp., under a $29.5 million contract with the AFRL, signed in November 2007. Targeting a one-year operational mission, ANGELS will demonstrate several new technologies, including a Space Situational Awareness (SSA) sensor, which will be evaluated in a limited region close to the DCSS of the Delta IV. “The vehicle will begin experiments approximately 30 miles (50 km) away from the upper stage and cautiously progress over several months to tests within several kilometers,” a Kirtland Air Force Base fact sheet explained. “As part of the research effort, ANGELS will explore increased levels of automation in mission planning and execution to enable more timely, safe and complex operations with a reduced operations footprint. AFRL engineers will maintain positive control of the spacecraft throughout the automation experiments, with ground-commanded authorization to proceed points, ensuring a “man-in-the-loop” throughout the experiment.”

ANGELS is also equipped with a GPS system for geosynchronous and high-performance accelerometers. The latter will employ advanced, NASA-provided algorithms to generate near-continuous navigation solutions and will precisely measure tiny satellite accelerations for enhanced guidance and navigation. An experimental on-board vehicle safety system will also explore methods to reduce the likelihood of collision with other space objects. “The ANGELS program will develop key technologies and capabilities for a broad spectrum of defense and civilian space missions,” explained Dr. Antonio Elias, then serving as Orbital’s Executive Vice-President and General Manager of the Advanced Programs Group, in the November 2007 news release. “Under AFRL’s leadership, this effort will help maintain the United States’ continuing technological and industrial superiority in space.”

The AFSPC-4 mission also marked the first use of the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) Secondary Payload Adapter (ESPA) on a Delta IV vehicle. The adapter, which provides an inter-stage “ring” for launching secondary payloads aboard Department of Defense Delta IV and Atlas V flights, is part of an effort to reduce launch costs and achieve minimal impact to the mission. Developed in the 1990s by the AFRL, together with the DoD’s Space Test Program (STP), the adapter ring was designed to accommodate a primary payload weighing up to 15,000 pounds (6,800 kg) and as many as six radially mounted secondary payloads, each weighing up to 400 pounds (180 kg). First trialed on the STP-1 mission in March 2007, launched via an Atlas V, the ESPA housed six military research satellites. More recently, it was employed to support NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) as a secondary payload alongside the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), lofted by another Atlas V in June 2009.

BELOW: Photos from our coverage of the SpaceX CRS-3 launch. All images credit Alan Walters and John Studwell for AmericaSpace. Images copyright 2014, all rights reserved, unauthorized use is prohibited.

– Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » Air Force OTV » AFSPC-4 »

Alan Walters, John Studwell,

We met at the AFSPC-4 launch second attempt. I am from Air Force Space Command and was there for the launch but had to leave before the rocket launched. I would like to use your photos of the launch as a future going away gift for some of the GSSAP action officers. Could you send me digital copies of the pictures of the launch that I could reproduce for that purpose only? I would greatly appreciate your cooperation and support. Thank you.

Tim Marburger

719 554-1033