Astronaut Dick Richards was five weeks from his first launch into space when the Challenger disaster cruelly snatched the opportunity from him. In January 1985, Richards had been named as Jon McBride’s pilot for Mission 61E, the ASTRO-1 science mission, scheduled for early the following March to observe Halley’s Comet and a multitude of astronomical targets. When Challenger lifted off on Mission 51L on 28 January 1986, McBride and Richards were in their seats in the simulator at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, working launch aborts. They briefly paused to step outside to watch their friends on the Challenger roar into space. Seventy-three seconds later, McBride and Richards’ mission vanished in a heartbeat, the shuttle program fell to its knees, and the NASA astronaut corps would never be the same again. Twenty-five years ago, this week, Richards made it to space with another crew, but the shuttle program would be a very different one.

In fact, the careers of Richards and Challenger’s pilot, Mike Smith, were entwined in many ways. For starters, they were the only two U.S. Navy pilots selected by NASA in its May 1980 astronaut class, and they had both been assigned to their first missions at the same time; Smith was paired with Dick Scobee and Richards with McBride. At first, it seemed to Richards that the pairings might happen the other way around. “I started getting all these simulation flights with Dick Scobee,” he remembered in his NASA oral history interview, and this led him to wonder if they were being primed for a mission assignment. Then, a few weeks later, Smith started doing simulations with Scobee and Richards began working extensively with McBride. Years later, Richards believed that delays to the long-awaited first shuttle launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., may have led to the decision. It would certainly be ironic to suppose that a simple quirk of fate and timing might have kept Richards from losing his life on Challenger’s final mission.

It is interesting that Richards’ 15-year career as an astronaut was already two-thirds over before he actually made it into space. The weeks and months after Challenger were devastating and one of his hardest jobs was supporting Mike Smith’s widow, Jane, in her grief. Two years later, in February 1988, he finally received assignment as pilot on STS-28, a classified Department of Defense assignment. The crew that he would be joining had actually been assigned to Mission 61N in December 1985, although the pilot for that flight, Mike McCulley, was substituted for Richards. Commander Brewster Shaw would be joined by mission specialists Jim Adamson, Dave Leestma—who retired from NASA earlier in 2014, after more than three decades of service—and Mark Brown.

With the pressure on getting Discovery and Atlantis into space before the end of 1988, on the STS-26 Return to Flight and classified STS-27 Department of Defense missions, Columbia found herself last in the queue and her launch was delayed until July and eventually the second week of August in the following year. However, despite being her first post-Challenger mission, the curtain of secrecy surrounding STS-28 showed no sign of being drawn back. Not until many years later would a few details of exactly what Brewster Shaw’s crew did in space finally begin to trickle out.

For his part, Dave Leestma described preparations for these top-secret missions as unusual and very cloak-and-dagger in nature. “Sometimes you had to disguise where you were going,” he said. “You’d file a flight plan in a T-38 [for] one place and go somewhere else, to try to not leave a trail for where you were going or what you were doing, who was the sponsor of this payload or what its capabilities were or what it was going to do. You had to be careful, all the time, of what you were saying.” STS-28 would transport the Department of Defense’s fourth major shuttle payload into orbit, but in the wake of Challenger the U.S. intelligence community began to reduce its reliance on the reusable fleet of orbiters by reverting to expendable boosters. Only payloads which were too large, too heavy, or too awkward to be reconfigured for an expendable launch remained on the shuttle. “The DoD did not like dealing with NASA,” said Leestma. “It was a constrained arrangement, but it worked very well and the DoD was happy with the product that they got in the end.”

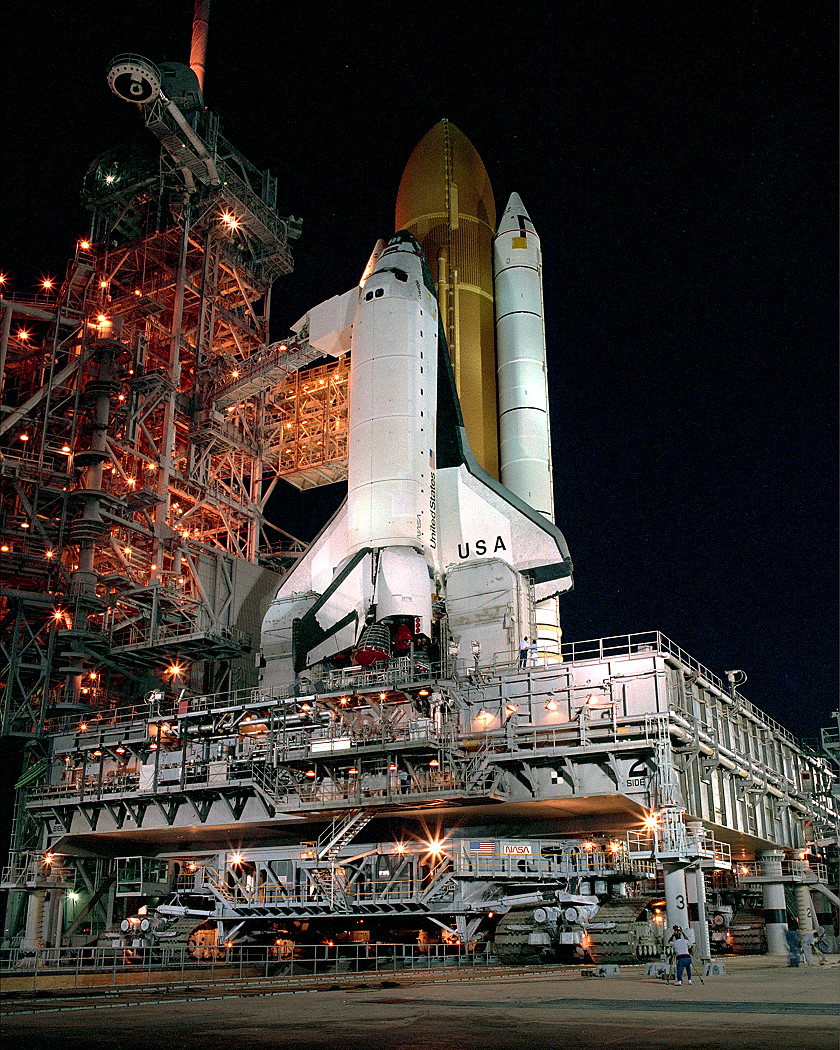

It had long since become standard practice in the build-up to such missions that the countdown was conducted in almost complete secrecy, with the public affairs commentary starting when Columbia emerged from the T-9 minute hold. Only after this point were the gathered spectators able to listen in to clipped intercom exchanges between the crew and launch controllers. A software problem caused the clock to be held for longer than planned, and a combination of haze and fog over the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) meant that STS-28 set off 40 minutes late at 8:37 a.m. EDT on 8 August 1989. Watching from the VIP area was NASA Deputy Administrator J.R. Thompson, who declared “We’re off to a good start on this mission.” Considering that the flight was historic, as the space agency’s flagship orbiter spread her wings once again, the official announcement from spokesman Brian Welch was flat and businesslike: Two hours after launch, he said, Shaw’s crew had been given a “Go” for orbital operations.

That was it.

The next five days would be similarly shrouded in secrecy and rumor.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace