As NASA and its international partners prepare for two briefings on Friday, 15 January, to discuss plans for the forthcoming One-Year Mission by U.S. astronaut Scott Kelly and Russia’s Mikhail Kornienko to the International Space Station (ISS), it is important to recognize that their long voyage will be the first of its type to occur in the 21st century. However, no fewer than three ultra-long-duration missions of 366 days, 438 days, and 379 days were conducted by cosmonauts aboard the Soviet—and later Russian—Mir space station in the 1980s and 1990s, producing a wealth of biomedical data and demonstrating that humans could survive in the microgravity environment for extended periods. In fact, tomorrow (9 January) marks the 20th anniversary of Valeri Polyakov seizing the record for the longest single space mission, as he surpassed 366 days in orbit, headed for an eventual total of 14 months away from the Home Planet. It is a personal and empirical record that Polyakov still holds to this day. In this two-part series of articles, AmericaSpace looks back at how humanity has pushed its experience base in space from just a few hours in 1961 to more than an entire Earth-year away from the cradle of its birth.

Enduring longer and longer spells in the harsh conditions of low-Earth orbit has been a significant goal from the beginning of the Space Age. Ever since Yuri Gagarin’s pioneering flight of 108 minutes on 12 April 1961, humanity has strived to make space less of a place to visit, and more of a place to live. Four months after Gagarin’s mission, fellow Soviet cosmonaut Gherman Titov spent a day in orbit, followed, in August 1962, by Andrian Nikolayev’s four days and in June 1963 by Valeri Bykovsky’s five days. (In fact, Bykovsky still holds the world record for the longest period of time spent alone in space.) The United States then took the lead, with Gemini V astronauts Gordo Cooper and Charles “Pete” Conrad achieving eight days in August 1965 and Gemini VII’s Frank Borman and Jim Lovell hitting 14 days the following December. This was the maximum flight duration expected for a round trip to the Moon, which was the primary goal of Project Apollo.

Yet longer durations would be required in order to reach further afield, particularly to eventually explore and settle Mars. In June 1970, Soyuz 9 cosmonauts Andrian Nikolayev and Vitali Sevastyanov eclipsed the U.S. record by spending 18 days aloft, but this was only the start. As part of its response to the triumph of Apollo, the Soviets developed the first Earth-orbital space station—Salyut 1—which was launched in April 1971 and successfully occupied by the crew of Soyuz 11 the following June. They returned to Earth after a record-setting 23 days, but were tragically killed when their spacecraft depressurized during an otherwise nominal re-entry. Hopes to stage longer missions (with Soyuz 12 originally expected to follow for about 45 days) were put on indefinite hold and the next Soviet crew would not launch until the fall of 1973.

By this time, with the curtain having fallen on the Apollo lunar program, the United States had again taken the lead, with its three Skylab crews having pushed the empirical endurance records from one month to two months and finally to three months. The first crew, commanded by Pete Conrad and including Joe Kerwin and Paul Weitz, spent a difficult 28 days in orbit in May-June 1973, working to repair their crippled orbital home, whilst Al Bean and his crew of Owen Garriott and Jack Lousma battled space sickness and problems with their Apollo spacecraft to triumphantly secure 59 days away from the Home Planet between July and September. Finally, from November 1973 until February 1974, the final Skylab crew of Gerry Carr, Ed Gibson, and Bill Pogue secured an 84-day record which would remain unchallenged for four years.

That challenge was met and surpassed in the six-year downtime following the close of the Apollo era and the dawn of the shuttle era. From July 1975 until April 1981, no U.S. astronaut entered space and it was a period dominated by Soviet spectaculars, centered around Salyut 6, which is today recognized as perhaps the first truly “international” orbital station. Although the Soviets hosted “guest” cosmonauts from different nations, they tended to welcome only Warsaw Pact or Communist-aligned fliers—including Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Vietnam—whilst spending increasingly lengthier periods of time in orbit. In early March 1978, Soyuz 26 cosmonauts Yuri Romanenko and Georgi Grechko exceeded the 84-day record set by the final Skylab crew.

However, under air sports rules, enshrined by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), a new record would only be officially recognized if it eclipsed the previous record by more than 10 percent. As a result, Romanenko and Grechko needed to remain aloft for at least 93 days. As circumstances transpired, they landed after 96 days, which represented a 15-percent jump over the achievement of Carr’s crew, and heralded the start of a chain of Soviet and Russian space endurance records which remains unbroken to this day, almost four decades later.

In general, the missions which followed tended to stick to the FAI rules. Cosmonauts Vladimir Kovalyonok and Aleksandr Ivanchenkov launched aboard Soyuz 29 in June 1978 and returned in November, after 139 days, thereby eclipsing the record of Romanenko and Grechko by 40 percent. Next up was the Soyuz 32 mission of Vladimir Lyakhov and Valeri Ryumin from February-August 1979, which spent 175 days in orbit, and represented a 25-percent leap over its predecessor. The sole “anomaly”—if it could be so-called—was the Soyuz 35 mission of Leonid Popov and Valeri Ryumin between April-October 1980, which spent “only” 185 days in space, a mere 9 percent increase. Although the two cosmonauts did secure the absolute spaceflight endurance record, and held it until late 1982, they did so unofficially, for their achievement was unrecognized by the FAI.

And yet it scarcely mattered. With the absence of U.S. human spaceflight endeavor in the late 1970s, there was also precious little of the dreary political crowing from the Soviets which had previously greeted each of their spectacular missions. To be fair, there no longer needed to be. Ken Gatland of the British Interplanetary Society (BIS) summed up the general thinking: “Once the record is broken, the U.S. has little chance of regaining it for many years, because there is no ongoing space station program.” Competition, for now, was dead.

However, returning to Earth’s gravity after up to six months in orbit carried its own difficulties. When Lyakhov and Ryumin touched down, they found it hard to even bear the weight of a small bunch of flowers. Presented to them in celebration of their success, it felt like a giant sheaf of wheat, although their strength steadily returned after a week or so. For Popov and Ryumin, on the other hand, they returned in fine shape and were able to walk for 30 minutes, unaided, a day after touchdown, and played tennis together a week or so later. This was testament to a strict regime of exercise, particularly during the final couple of weeks of each mission. In the West, the detail of these flights was shrouded in secrecy, hidden behind the Iron Curtain, and consequently appeared somewhat dull. In a satirical cartoon from David Austin, published in New Scientist in September 1978, the routine of longer and longer missions was presented by a pair of NASA men, standing side by side. One of them held a newspaper, emblazoned with the headline that the Soviets had just secured another endurance record, and remarked: “Another long, boring shuffle forward for mankind!”

Boring, perhaps, from the perspective of lack of information, but necessary, for a little more than a decade hence, the United States would come to increasingly court Russian expertise as it sought to establish its own multi-national space station in orbit. The new Salyut 7 outpost, launched in April 1982, was first occupied by the Soyuz T-5 crew of Anatoli Berezovoi and Valentin Lebedev from May. Despite an illness suffered by Berezovoi in early November, which prompted some mutterings of an early end to their mission, the two cosmonauts exceeded the 175-day and 185-day records of their predecessors and returned to Earth on 10 December, after 211 days in orbit. It has been suggested by space analysts Phillip Clark, Dave Shayler, and the late Rex Hall that 7.5 months—maybe 225 days or more—was the original expectation, with Clark noting that Berezovoi and Lebedev took air samples of the Salyut 7 atmosphere, thus hinting at some form of atmospheric contamination, although this was never confirmed.

Whatever the reality, the cosmonauts certainly landed in highly undesirable circumstances. Their Soyuz capsule touched down in the hours of darkness, in the thick of a mid-winter blizzard, with weather forecasts predicting 13 mph (21 km/h) winds, temperatures of -9 degrees Celsius (15.8 degrees Fahrenheit), and visibility of no more than 6.2 miles (10 km). High winds dragged the descent module over a small incline, causing it to roll down a hill, exacerbating the discomfort of the cosmonauts, who had already been unable to undertake their normal pre-landing physical conditioning. One of the rescue helicopter pilots spotted their flashing beacon and made an unsuccessful attempt to land nearby. Eventually, ground vehicles were sent it to pick up Berezovoi and Lebedev.

Exactly when the next record was planned to be broken remains unclear, for 1983 turned into a troubled year for the Soviets, including one mission which failed to dock with Salyut 7 and another, in September, which suffered a launch vehicle explosion on the pad and very nearly claimed the lives of its two-man crew. Both of these unsuccessful flights, ironically, included cosmonaut Vladimir Titov, who would go on to become one of the first men to spend an entire Earth-year away from the Home Planet.

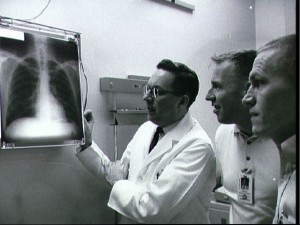

As circumstances transpired, it was the three-member crew of Soyuz T-10—Leonid Kizim, Vladimir Solovyov, and physician-cosmonaut Oleg Atkov—who pushed the 211-day endurance record toward the eight-month mark. Their flight, from February-October 1984, lasted a record-breaking 237 days, encompassed no fewer than six EVAs for repair and installation work and hosted two visiting crews. Certainly, the presence of Atkov was deliberate, as a means of monitoring the physiological and psychological adaptation of himself and his crewmates during the mission. (Interestingly, Valeri Polyakov served as Atkov’s backup.) In their Springer-Praxis volume, Soyuz: A Universal Spacecraft, Rex Hall and Dave Shayler noted that Atkov’s inclusion on Soyuz T-10 was part of a deliberate Soviet attempt to include a physician aboard every future record-setting duration mission.

This did not entirely come to pass. By the spring of 1985, plans were in work for a nine-month flight, featuring cosmonauts Vladimir Vasyutin, Viktor Savinykh, and Aleksandr Volkov, probably to be launched in May. According to Phillip Clark, it is possible that Valeri Polyakov may have been intended as the third-seater on a short visiting mission, later in the year, thereby providing the presence of a medical specialist to provide observation of the long-duration crew. However, all of these plans were thrown into disarray in February, when Salyut 7 lost all attitude controllability and a rescue crew of Savinykh and Vladimir Dzhanibekov were launched in June to revive its fortunes. They succeeded and a new crew of Vasyutin, Volkov, and Georgi Grechko was launched in September. Dzhanibekov and Grechko returned to Earth shortly afterwards, leaving Vasyutin, Savinykh, and Volkov aboard Salyut 7 until—it was hoped—the spring of 1986. Landing in mid-March, this would produce a mission of 282 days for Savinykh. Sadly, Vasyutin fell ill in November 1985 and the entire crew returned to Earth. Rather than a new empirical record of more than nine months, Savinykh came back home after 168 days. It would be left to another cosmonaut to push the Soviet Union’s endurance capabilities further.

And the identity of that cosmonaut morphed and changed in late 1986 and early 1987. As will be discussed in tomorrow’s AmericaSpace article, the new Mir space station would see the endurance records continue to fall like ninepins. By the end of 1987, a human being would have spent almost 11 months away from Earth and by the close of 1988 a full year would have been chalked up by another crew. It was the beginning of a series of flights which would begin to establish the kind of baseline medical data which will someday prove critical as humanity prepares to explore deep space and head for Mars.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace