Had history smiled with more favor, ASTRO-1 might have taken place almost three decades ago, but the space shuttle’s first mission totally dedicated to astrophysics was repeatedly delayed in the aftermath of the Challenger accident and eventually achieved low-Earth orbit 25 years ago, this week, in December 1990. Affixed into Columbia’s payload bay, ASTRO-1 comprised a trio of ultraviolet telescopes—Johns Hopkins University’s Hopkins Ultraviolet Telescope (HUT), the University of Wisconsin at Madison’s Wisconsin Ultraviolet Photopolarimeter Experiment (WUPPE), and, provided by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) of Greenbelt, Md., the Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (UIT)—to scour the distant Universe and examine supernovae, white dwarfs, quasars, and galactic nuclei. Co-manifested on STS-35 was the Broad Band X-Ray Telescope (BBXRT), which pursued its own ground-commanded program of astronomical inquiry. Yet, as outlined in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, the cruel fortune which had befallen the mission was not yet done and the gremlins of bad luck continued to dog Columbia’s 10th space voyage.

Early on 3 December 1990, less than 24 hours into the mission, the Instrument Pointing System (IPS)—which carried the responsibility for raising and directing the three ultraviolet telescopes—started to experience difficulty “locking” onto its guide stars. An alternative plan was quickly worked out to help the astronauts to manually point the telescopes and track targets on the HUT’s television camera using a hand paddle. This worked reasonably well and allowed them to aim the telescopes with an accuracy of around three arc-seconds, but it was not a positive start. “The mood is one of concern,” said Flight Director Bob Castle. “We’d certainly like the system to work perfectly, but there is no panic. People are working to solve the problem and we have confidence we will solve [it] in a fairly short time.”

Worse, though, was to come. Late the previous evening, Commander Vance Brand had picked up the scent of warm electrical insulation, which was traced to an overheated Data Display Unit (DDU). It was bad news, for the twin DDUs were critical in enabling the astronauts to control the IPS and the telescopes. This threw the observation plan at least six hours behind schedule, and by the 4th more than 20 astronomical targets had been lost. Gradually, the pace quickened and the telescopes were steadily revived. By the third day of the mission, the situation had improved sufficiently for ASTRO-1 to perform automatic acquisitions of targets.

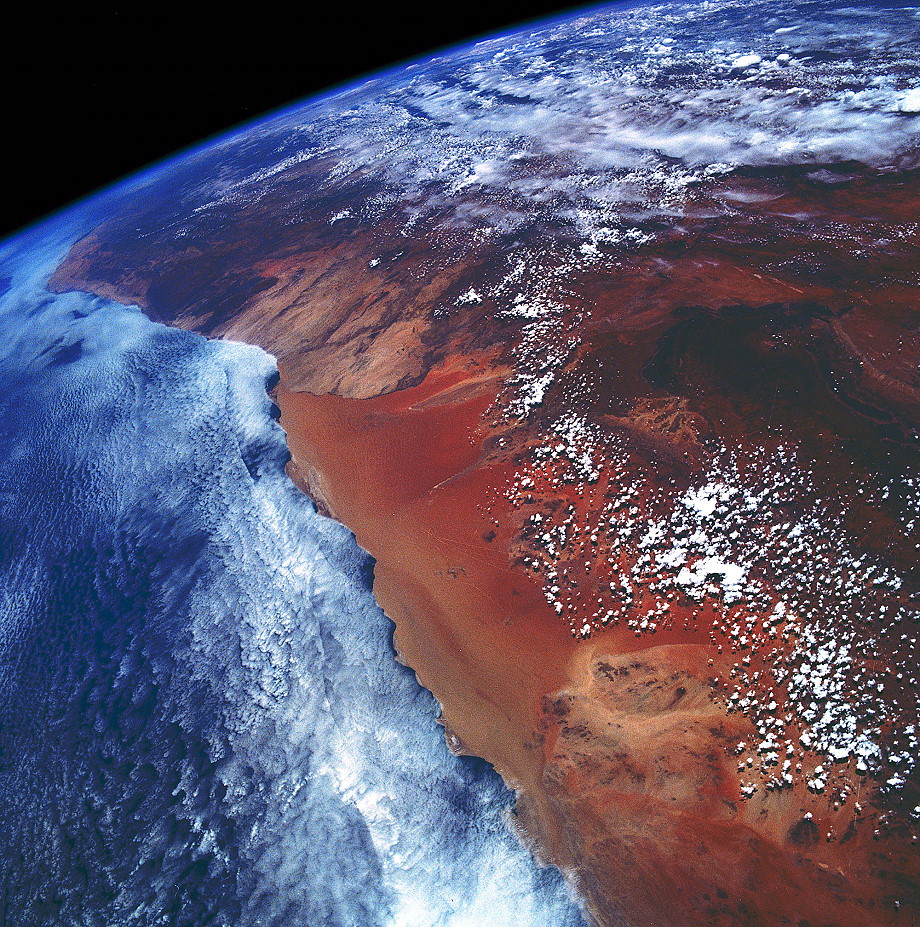

However, it remained far from ideal, as the control of the IPS and the telescopes was being done from a single DDU. Then, early on the 6th, the second DDU overheated and itself failed. Mission Specialist Jeff Hoffman examined its internal components and vacuumed out some lint from its air-intake filters, but the device remained dead. By this stage, 70 of a projected 250 observations had been completed—a huge success, in light of the problems—but the failure of the second DDU was a devastating blow for the mission, with at least one scientist questioning whether he ought to cry or grin from ear to ear. The likelihood of a fully successful mission hung by a thread. “Suddenly, we couldn’t point,” Mission Specialist Bob Parker later told the NASA oral historian. “The ground came up with a scheme where they could control the telescopes, but what they couldn’t do in near-real-time was guide the telescopes. Everybody put a brave face on it, but it was a far cry of what we had intended it to be.” In fact, the crew had little to do but enjoy the glorious view of Earth, drifting serenely “below” them. This view, however, was somewhat fleeting on STS-35, depending on the observation schedule. “We weren’t pointed at the Earth very much,” admitted Mission Specialist Mike Lounge, “which was a little unusual, because the other flights [had their] payload bay down at the Earth all the time. We were pointed at the stars, so we could be, depending on the target, any attitude.”

Once more, the remarkable ground specialists managed to bounce back from the DDU failures, and by 7 December they were able to command all but the final motions of the telescopes. It was then left to the astronauts to fine-tune each observation. Revised procedures involved operating the telescopes sequentially—firstly UIT, which had the largest field of view, followed by HUT, and lastly WUPPE—and even the BBXRT was indirectly affected, since it had to cease its work whenever Columbia entered a “safe” attitude.

The crew established themselves into a routine, working effectively and efficiently with their colleagues on the ground to maximize scientific output. Typical clipped exchanges between Payload Specialist Sam Durrance and his backup, Ken Nordsieck, on the space-to-ground communications link were crisp and terse: “Sam, you’re within an arc-minute … Okay, give me a ‘mark’ when you’re happy … The data’s looking real good, Sam … We’re seeing lots of photons down here.” Overall, ASTRO-1 recovered from its troubles to make 231 observations of 130 different celestial objects and ran for 143 hours to accomplish 70 percent of its pre-mission goals. Despite being affected by the problems with the observatory, the BBXRT also returned an enormous volume of data.

Although the main thrust of the flight had been the observatory in the payload bay, the astronauts participated in a number of other activities. One of the most noteworthy was the “Space Classroom,” which gave Jeff Hoffman the honor of becoming the first person to wear a tie in orbit. “All the male teachers wore ties,” he told Mission Control. “I know nobody has ever worn a tie in space, so I thought I’d give it a try and see what it looks like.” Then, with the tie secured in place by a piece of Velcro, he introduced the first school lesson ever transmitted from space. Years later, in his NASA oral history, Hoffman provided some additional detail on the tie story. “My uncle was a New York lawyer,” he recalled, “and he represented a lot of foreign firms. Among them was the Hermès Corporation, which makes fancy silk scarves and silk ties.”

According to Hoffman, one of Hermès’ publicity agents gave NASA the idea that the corporation was using a visit to the space agency for commercial purposes. NASA canceled the visit, refusing to allow the use of its government-furnished facilities for advertising. Fortunately, Hoffman’s uncle put the agent in touch with Hoffman to patch things up. “It was very nice,” he said later, “because we ended up getting invited to a lot of the Hermès parties.” When Hoffman mentioned that he wanted to take a tie with him into space, the corporation was only too happy to provide one. But there was a problem. Hermès’ ties were all silk and NASA fire-safety guidelines demanded cotton. Without hesitation, they made him a cotton tie—a beautiful patterned one with an image of an astronaut emblazoned upon it.

The classroom experiment was part of a project entitled “Assignment: The Stars” and was intended to encourage students’ awareness of science, mathematics, and engineering. The main emphasis was upon the electromagnetic spectrum, which Durrance likened to a musical symphony. To press the analogy, he played two taped versions of the same piece; the first, he explained, was unrecognizable because its high and low notes had been removed, whereas the second turned out to be the theme from Star Wars. “You need to hear all the notes,” Durrance told the students, “to appreciate the sound.” Likewise, he concluded, the Universe was playing its own symphony of sorts, across the electromagnetic spectrum, some parts of which were harder to detect than others.

In addition to speaking to schools, the astronauts also made ham radio contacts and a couple of days before landing an important visitor arrived at the Mission Control Center (MCC) in Houston, Texas. Eduard Shevardnadze, then-foreign minister of the Soviet Union, was planning to speak to the STS-35 crew and Vance Brand—who spoke Russian as a result of his involvement in the Apollo-Soyuz mission—had put together a short speech. (The nature of dialog between the United States and the Soviet Union had reached such a level of cordiality by this time that, had Columbia launched as planned, in May 1990, her crew was scheduled to perform a ship-to-ship voice link-up with cosmonauts Anatoli Solovyov and Aleksandr Balandin aboard the Mir space station; the first time that such contact had ever been made.) Unfortunately, in the case of Shevardnadze, the news that Columbia would be returning a day earlier than planned meant that the astronauts’ sleep patterns changed. It turned out that Brand would be asleep at the time of the Shevardnadze “comm pass.” At first, NASA decided to simply cancel the event, because it was unfair to wake him in the midst of sleep. Then the agency changed its mind. Hoffman, Lounge, and Durrance were awake, on the “graveyard” shift, when the call came up that they would be speaking to Shevardnadze on their next orbital pass!

The three men exchanged anxious glances. One of them poked his head downstairs into the darkened middeck. Brand was sleeping soundly. They knew that he would be responsible for landing the orbiter and did not want to wake him. It was Hoffman who came to the rescue. “I had studied a little bit of Russian in college,” he said, “but that was a long time ago.” When the time for the comm pass arrived, he produced a couple of sentences and thought no more about it. One person who was listening intently, though, was Johnson Space Center (JSC) Director Aaron Cohen, who bubbled with excitement over Hoffman’s performance. Shortly after landing, Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh visited JSC and Hoffman, whose wife, Barbara, was British, delicately asked Cohen if there was any chance that they could be allowed to see the royal couple. Cohen did better than that. He was so impressed by the astronaut’s diplomatic skills that he asked the Hoffmans to serve as the Queen and Prince Philip’s guides. If it turned into a memorable experience for Barbara Hoffman, then it certainly also paid dividends for her father, back home in England, who got free drinks at the pub for months afterwards.

Shortly before 9 p.m. PST (midnight EST) on 10 December 1990, Brand and Pilot Guy Gardner fired Columbia’s Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines for the 231-second de-orbit burn and an hour later, at 9:54 p.m. PST on the 10th (12:54 a.m. EST on the 11th), the vehicle swept through the darkness to alight on Edwards’ concrete Runway 22. “We’re home,” radioed an elated Brand as Columbia rolled to a halt, “and glad to be back.”

There were a few niggling glitches elsewhere, however, included a blocked waste water line to the toilet, which meant that the urinal was unusable. Mike Lounge had the unenviable task of tending to the latter. “It was messy,” he told the NASA oral historian, “and we had to stow the waste from the waste tank into plastic bags and seal them up. It was stinky. It was not glamorous space flight!” For Jeff Hoffman, it also highlighted the somewhat ludicrous effort to prepare for each mission. Before launch, the astronauts participated in a bench review, inspecting each and every item to be carried aboard. Most of the items were for contingencies and almost certainly would never be used … but the all-male crew noticed a whole boxful of female urine collectors!

“There’s seven men on this flight,” they protested. “Why are we carrying a box of female urine contingency devices?”

“Well,” came the reply, “some flights have women, and some don’t, but the paperwork that would be involved to take this thing on and off, depending on whether you had women on the flight, would be so onerous that it’s easier just to leave it on every flight!” During the mission, as they worked through the limited supply of male urine collectors, these tended to leak tiny yellow bubbles. Fortunately, the men’s sense of smell was very much depressed, partly due to fluid shifting in microgravity, although Hoffman remembered working with Lounge to mop up urine deposits with old socks. “It was probably just as well,” he concluded, “that there weren’t any women on that flight. It was pretty gross!”

He pitied the technicians who had to clamber into Columbia’s middeck after landing to begin the process of cleaning everything up. …

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 50th anniversary of the first piloted rendezvous in space, between America’s Gemini VII and VI-A spacecraft … and the hazardous journey to achieve it.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace