When the STS-54 shuttle crew released their official crew patch in the summer of 1992, they paid tribute to two important payloads aboard their mission. The first was NASA’s fifth Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-F), which would form the latest component in a critical geostationary-orbiting constellation to maintain near-continuous voice and data communications between the shuttle and other important scientific spacecraft with ground stations. Attached to a Boeing-built Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster, TDRS-F would be deployed from Shuttle Endeavour’s payload bay late on the first day of the six-day mission. Within the bright-red circular frame of the STS-54 patch, a fearsome bald eagle held an enormous, eight-pointed star in its talons and was about to add it to a collection of four stars already in place. According to the crew, this represented the placement of the fifth TDRS into orbit, alongside its four cousins, launched in 1983, 1988, 1989, and 1991. Behind the eagle, the glorious blue and white Earth was juxtaposed with the unfathomable blackness of space; a blackness which, on this patch, was conspicuously devoid of stars. “The blackness of space,” noted the patch description, “represents our other primary mission of carrying the Diffuse X-ray Spectrometer to orbit to conduct astronomical observations of invisible X-ray sources within the Milky Way Galaxy.”

In command of the STS-54 mission was John Casper, a veteran of the classified STS-36 shuttle flight. His four crewmates included fellow veterans Don McMonagle as pilot and mission specialists Greg Harbaugh and Mario Runco, together with “rookie” Susan Helms. Today a lieutenant general in the U.S. Air Force and commander of the 14th Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) and the Joint Functional Component Command for Space at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., she holds the record for achieving the highest rank of any female military astronaut. On STS-54, she also became America’s first active-duty military female spacefarer.

Within months of entering NASA in January 1990, Helms was persuaded to join the ranks of the all-astronaut rock band, “Max Q,” playing keyboards. Helms had taken lessons for 11 years, as well as having played concert drums and xylophone in marching bands and choirs and as part of a jazz combo. In an interview with Michael Cassutt, she described her tastes as “pop, Top 40, everything but country and western,” and fellow Max Q member Kevin Chilton described her as “hugely talented” and capable of listening to a song on the radio and playing it. “She was able to teach us harmonies,” said Chilton. On STS-54, Helms carried a mini-keyboard as part of her personal kit and managed to tap out a one-finger version of the Air Force anthem “Wild Blue Yonder” whilst in orbit.

In addition to TDRS-F, Endeavour was carrying the twin detectors of the Diffuse X-ray Spectrometer, mounted on Hitchhiker plates on opposite walls of the forward payload bay. This instrument originally formed part of a much larger Spacelab payload, known as the Shuttle High Energy Astrophysics Laboratory (SHEAL), and would have flown alongside the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Broad Band X-Ray Telescope (BBXRT). However, the completion of the latter, ahead of schedule, and the deletion of another instrument from the ASTRO-1 mission, caused it to be moved forward on the shuttle manifest and it flew in December 1990. As for the DXS, it was moved around as a secondary payload on a couple of flights, before coming to rest on STS-54.

Designed to acquire the first-ever spectra of the diffuse low-energy “soft” X-ray background in the energy band between 0.15-0.284 keV, the DXS comprised a pair of large-area lead-stearite Bragg crystal spectrometers. Each contained a curved panel of Bragg crystals mounted above a position-sensitive proportional counter, across which a spectrum would be dispersed to enable all portions to be measured simultaneously. However, whilst all wavelengths were observed at the same time, the various wavelengths came from different directions in the sky, and therefore the spectrometers “rocked” backward and forward to obtain complete spectral coverage along an entire arc of the sky. The two spectrometers and their associated instrumentation were built at the Space Science and Engineering Center at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Unique in its ability to “sort” detected X-rays by wavelength, the DXS identified large quantities of hot gas in the interstellar medium, close to our Solar System. Although classed as a secondary payload, the importance of the instrument was such that provision was included in the STS-54 manifest for a one-day extension to seven days, “if DXS requires additional time to achieve mission success.” Although scheduled to fly for less than six days, Endeavour was equipped with enough consumables to support a seven-day “basic” mission, plus two additional days to cater for unforeseen contingencies, such as weather or other difficulties.

As 1992 drew to a close, STS-54 appeared to be a relatively “vanilla” mission, planned for mid-January of the following year. Then, on 25 November, NASA announced its decision to add EVAs onto three future shuttle missions to “fine-tune the methods of training astronauts for assembly tasks in space” and “increase the spacewalk experience levels of astronauts, ground controllers and instructors.” The agency noted that such excursions would only be added on the proviso that they did not impact primary mission objectives … and the first flight to benefit from the change was STS-54. It had long been recognized that an immense number of EVAs, later to be nicknamed “The Wall of EVA,” would be needed to assemble and maintain Space Station Freedom, and the difficulties experienced by the STS-49 crew during their effort to capture the Intelsat-603 satellite in May 1992 had led them to lobby for more expertise within the astronaut corps.

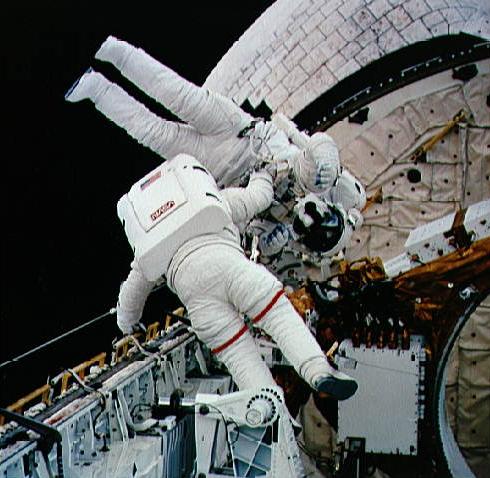

In fact, on the first day of 1993, of the 90 or so astronauts on active flight status, only eight had EVA experience. For STS-54, Greg Harbaugh and Mario Runco had undergone generic spacewalk training, in case they had to go outside and manually close the payload bay doors, but their work moved swiftly into high gear in the final days before and after Christmas as plans were finalised for a five-hour EVA. Their tasks included moving around Endeavour’s payload bay with and without large objects (including each other) as well as completing close alignment tasks and installing equipment. It was mandatory for their EVA to conclude at the scheduled time, because it was assigned a lower priority than the DXS observations, which had to be suspended whilst Harbaugh and Runco were outside. After the mission, it was intended that the spacewalkers would repeat their activity in the Houston water tank to help improve future training practices.

Liftoff of STS-54 on 13 January 1993 was delayed by a little more than seven minutes to await the resolution of a Launch Systems Evaluation and Advisory Team violation. Under the combined thrust of her three main engines and twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), Endeavour speared for the heavens at 8:59 a.m. EST and successfully entered a 28.45-degree-inclined orbit shortly afterward. Six hours and 13 minutes into the mission, high above the Pacific Ocean, to the north of Hawaii, the TDRS-F payload and its attached IUS were released and Casper and McMonagle manoeuvred the orbiter to a safe separation distance.

An hour after deployment, the first stage of the IUS ignited to achieve geostationary transfer orbit, and the second stage fired some five hours later to circularize the orbit. Thirteen hours after launch, the TDRS separated from the IUS and underwent a complex process of unfurling its solar arrays, space-to-ground communications boom, and its C-band and single-access antennas. The numerically renamed “TDRS-6” thereby became the fifth operational satellite in a constellation which supported the shuttle and important scientific missions, including Hubble and the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory. (An earlier satellite, TDRS-B, was lost in the Challenger accident.) On Endeavour’s seventh orbit, the DXS instrument began scanning. Despite problems due to high particle counts, which triggered a high-voltage shutdown, an additional 15 orbits of data collection were authorized to complete its objectives. The spectrometers acquired a total of more than 80,000 seconds of good data.

Elsewhere, inside Endeavour’s crew cabin, depressurization was executed on the third day of the flight in anticipation of Harbaugh and Runco’s EVA. The two men entered the floodlit payload bay at 5:48 a.m. EST on 17 January, closely monitored by Susan Helms, who acted as the intravehicular crew member. During the excursion, the spacewalkers translated themselves around the payload bay, both with and without large items and climbed into foot restraints without the benefit of handholds. “To simulate carrying a large object,” noted NASA’s pre-mission press kit, “the astronauts will carry one another.” They also worked with the IUS “tilt table” at the rear of the bay and returned to the airlock after four hours and 27 minutes. Yet the spacewalk brought the shuttle program’s EVA total to barely 110 hours, far short of the 400 hours anticipated for construction of Space Station Freedom, and in response to this problem NASA added two further EVAs to STS-51 and STS-57.

Despite their numerical order, STS-51 was scheduled to occur after STS-57, with launch originally scheduled for July 1993. In the first week of February, NASA announced its intention to “continue extravehicular activity tests” with spacewalkers Carl Walz and Jim Newman. “The addition of the spacewalk to STS-51 will allow us to continue refining our knowledge of human performance capabilities and limitations during spacewalks,” said Ron Farris, the chief of the EVA Section at the Johnson Space Center. “This EVA constitutes a continuing commitment by NASA to advance our preparations for future EVA missions, such as the Hubble Space Telescope servicing and Space Station Freedom assembly flights.”

Two weeks later, on 17 February, an EVA by astronauts David Low and Jeff Wisoff was added to STS-57, then scheduled for late April. The scope of this mission hinted at its importance for the forthcoming Hubble servicing flight: with “procedures using the Shuttle’s mechanical arm” planned to “involve work by astronauts on a platform at the end of the Shuttle’s arm.” Moreover, when combined with STS-54 and the spacewalks already planned for the first Hubble servicing mission, STS-61 in December, this meant that NASA was aiming to fly four EVA flights in 1993 … tying a record previously set in 1984. “In a sense,” said Ron Farris, “it will be a banner year for EVA and will be somewhat representative of the EVA efforts required to build and maintain Space Station Freedom.”

Spacewalking induced a peculiar sensation in Mario Runco. Years later, describing the experience to a Smithsonian interviewer, he related a free moment in the EVA, waiting for Harbaugh to finish up a task. “I was standing, facing outboard on a work platform,” Runco said. “The platform locks your feet down and frees your hands for work.” During underwater training before launch, he enjoyed bending over backward at the knees (“sort of like doing the limbo”) and expected it to be a comfortable stretch, relieving all of the pressure points induced by his suit. “But in space, the viscosity of the water wasn’t there to slow me down,” he continued, “so when I relaxed to stand up straight again, the suit ‘twanged’ forward at what seemed like an incredible velocity. It really felt like I would come right out of the foot restraint and go tumbling off into space, even though I knew I couldn’t.” Gazing directly into the ethereal blackness of space, Runco was brought face to face with what he could only describe as a first-hand glimpse at God’s handiwork.

Aside from the drama of the EVA, the five astronauts oversaw a range of medical and biological experiments in the middeck, monitoring the effect of microgravity exposure upon the skeletal muscles of rodents, growing seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana (a small, cress-like plant, with white flowers), and supporting 28 commercial investigations into biomedical testing and drug development, control of ecological life-support systems, and the agricultural manufacture of biological-based materials. On a somewhat lighter note, a collection of children’s toys were flown as an educational resource. The “Physics of Toys” investigation involved schools in the hometowns of four of the astronauts and was specifically focused on elementary children. “Live” demonstrations on 15 January were led by John Casper, and the toys involved a car and track, klacker balls, a basketball, magnetic marbles, swimmers, a mouse, and a balloon helicopter.

Endeavour’s departure from orbit on the morning of 19 January proceeded without incident, and the orbiter touched down in Florida at 8:37 a.m. EST, concluding a mission of just a few minutes shy of six full days. STS-54 had begun its life as a “vanilla” shuttle flight, which had turned to chocolate, and its importance for the future construction of the International Space Station (ISS) would be truly profound.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the fateful decisions made in the hours, days, weeks, and months before 28 January 1986, when Challenger brought the shuttle program to its knees.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace