The “Month of Pluto” is now upon us, as NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft—launched atop an Atlas V 551 booster from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., way back in January 2006—enters the final two weeks before its long-anticipated rendezvous with the dwarf world Pluto, its large binary companion Charon, and a system of at least four tiny moons: Nix, Hydra, Kerberos, and Styx. In doing so, New Horizons will bring full-circle humanity’s first-time exploration of each of the traditionally accepted nine planets in the Solar System; although Pluto was officially demoted to the status of dwarf planet in 2006, fierce debate continues to rage about its nature. Over the coming days, as our resolution of Pluto grows clearer, as our first close-range maps begin to take shape and as a tidal wave of scientific data floods back to Earth across a gulf of more than 2.9 billion miles (4.8 billion km), AmericaSpace’s New Horizons Tracker and a series of articles by Mike Killian, Leonidas Papadopoulos, and myself will follow the spacecraft’s progress as it seeks to make this unknown world known.

At times like these, it is difficult not to let the excitement take hold, for despite its 2006 demotion in status, Pluto has for many people around the world—this writer included—always been a planet and will remain so. From nursery rhymes to schooltime mnemonics, the list of nine planets of the Solar System has always ended with “ … and Pluto.”

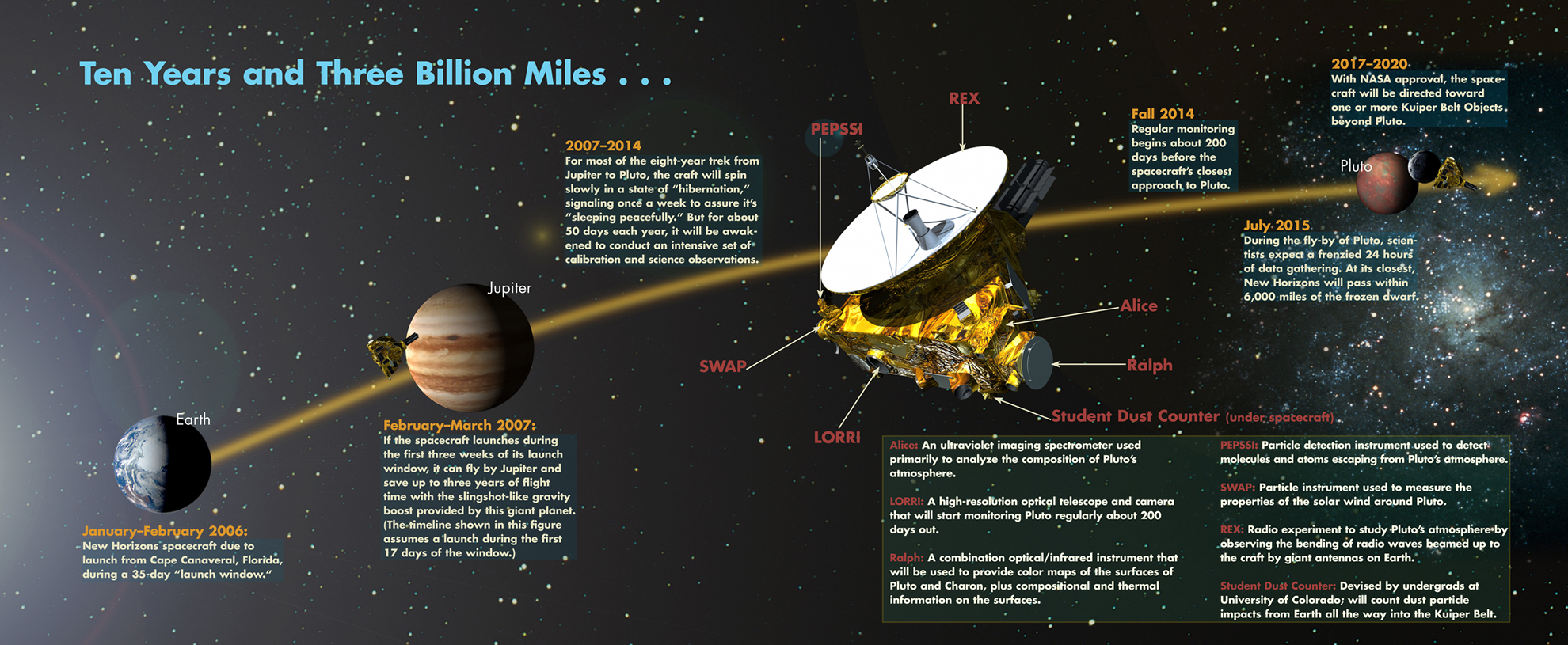

In next weekend’s Pluto series, AmericaSpace will reflect upon our changing attitudes toward this far-off world, but it is quite remarkable that just 17 days from now we will be rewarded with our first-time glimpse of a new world, whose existence has been conclusively known for more than 85 years. Already, our first color images of the Pluto-Charon system in motion—as detailed in a recent article by Leonidas Papadopoulos—were returned to Earth in early June 2015 by the Multicolor Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC) on New Horizons’ Ralph instrument, revealing a beige-orange object, circled every 6.4 days by its murky gray-white companion. Moreover, as Pluto rotated, highly contrasting differences in albedo were readily apparent, even from a distance of 30 million miles (50 million km), suggesting that the surface soon to be discerned by New Horizons’ science payload will turn up a great deal of surprises and generate as many questions as answers.

In last week’s Pluto history series, our species’ foiled and fruitless attempts to explore this mysterious celestial system were highlighted. Early proposals to redirect Voyager 1 to a Pluto-Charon flyby in the spring of 1986 came to nothing, due to the greater scientific emphasis upon investigating the dynamics of Saturn’s rings and its large moon, Titan, the consequences of which produced a different trajectory out of the Solar System. Yet as the years passed, Pluto drew greater fascination, with a tenuous, nitrogen-dominated atmosphere detected in 1988 and the discovery of the first bodies of the “Kuiper Belt,” exterior to the orbit of Neptune, in 1992. At around the same time, efforts to develop a Pluto Fast Flyby (PFF), laden with visible imaging, ultraviolet spectrometry, radio science, and plasma instruments, were conceived, but insufficient funding and unacceptable mass-growth ultimately proved its downfall. PFF was for a time reinvented as the Pluto Kuiper Express (PKE)—additionally tasked to explore one or two Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs)—but unacceptably large cost increases doomed it to cancelation in the fall of 2000.

However, the pressure from the scientific community to mount a mission to Pluto was strong. The Planetary Society delivered more than 10,000 letters to U.S. senators that fall, in an effort to have it reinstated. “We must go there,” stressed the Solar System Exploration Subcommittee (SSEC) in an October 2000 letter to Dr. Ed Weiler, NASA’s Associate Administrator for Space Science at the agency’s Washington, D.C., headquarters. “The information needed is mostly unobtainable from telescopic observations, even allowing for future improvements. Though small, Pluto has an atmosphere and is expected to have internal dynamic processes. The Pluto-Charon binary planet system has no other Solar System analog in its tidal evolution, except possibly Earth and our companion, the Moon. From our perspective, close in to the Sun, this is a mission to the frontier of the Solar System, an appealing aspect to both scientists and the public.”

At length, in December 2000, NASA opened up an Announcement of Opportunity for a flyby mission, whose cost was capped at $500 million. Following the closing date in March 2001, a planned “downselect” of the five submitted proposals was initiated, leading to the selection of two finalists in the summer. Although there was no restriction on the launch date, it was considered desirable to reach Pluto by 2015, due to the increasing likelihood that the dwarf world’s thin atmosphere would freeze as it progressed farther from the Sun on its highly eccentric, 248-year orbit.

“Five proposals were turned in to NASA,” wrote Dr. Alan Stern of Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) Space Studies Dept. in Boulder, Colo., in a New Horizons historical overview paper. “I understand that three were apparently strong contenders and two were not.” One of the strong contenders was the Stern-led New Horizons, whilst the others originated from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., one headed by Dr. Laurence Soderblom of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Science Center in Flagstaff, Ariz., and the other by Dr. Larry Esposito of the University of Colorado at Boulder. One key issue of timing surrounded the usefulness of a Jupiter Gravity Assist (JGA), which carried the potential to shave up to five years off the journey time, but necessitated a launch in the 2004-2006 timeframe. “The Soderblom et. al. proposal cleverly involved ion propulsion in order to remove the 2004-2006 JGA launch window constraint,” explained Dr. Stern. “The Esposito et. al. and Stern et. al. proposals both involved conventional-propulsion JGA trajectories.”

As Principal Investigator (PI), one of Dr. Stern’s tasks had been to conceive a name for his mission proposal. “My first reaction, of course, like everyone else’s, was to find a suitable acronym,” he reflected in a May 2005 article in The Space Review. “After all, that’s just what you reflexively do in the space business.” Unfortunately, with a Pluto Kuiper Belt exploration mission, this philosophy produced a plethora of Ps and Ks and Es and Ms, yielding largely unacceptable acronyms such as POPE, PUSS, PIMPLE, PLATITUDE, PIP, and POPE, “and a couple of others I won’t mention in mixed company.” As a result, Dr. Stern requested his team to conceive of something else; less of a “name,” and more of a “brand.” Some of the resulting suggestions—“X,” “Tombaugh Explorer,” “New Frontiers,” “One Giant Leap,” and “Voyager 3”—were intriguing, but carried their own problems.

“I recall taking a long Saturday run across Boulder to work on ideas of my own,” Dr. Stern remembered in The Space Review. “I quickly decided that the very positive word ‘New’ should be part of the name for PKB, for it was new in many ways. Then, as I waited for a streetlight to change, near the intersection of Foothills and Arapahoe, and looked west to the Rocky Mountains on the horizon, it just hit me. We could call it ‘New Horizons’, for we were seeking new horizons to explore at Pluto and Charon and the Kuiper Belt and we were pioneering new horizons programmatically took, as the first-ever PI-led outer planets mission.” In his mind, it was “a great, forward-looking, positive metaphor for exploration,” carrying connotations of “such pleasant things, like rainbows.” After conferring with his team, the name was official by February 2001.

Shortly after the acceptance of New Horizons, NASA received Congressional approval for its “New Frontiers” program, tasked with executing a series of medium-class planetary exploration missions, of greater cost and complexity than the “Discovery” program—which has produced such ventures as Mars Pathfinder and its Sojourner rover, the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) orbiter, and the Dawn mission to the small worlds Vesta and Ceres—and of substantially lower cost and complexity than the Flagship Program, which spawned the Galileo and Cassini spacecraft to Jupiter and Saturn respectively. New Frontiers has since expanded to include the 2011-launched Juno mission to Jupiter and will also encompass the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) to gather and return samples from the asteroid Bennu, which is planned for launch in 2016. Following the birth of New Frontiers, NASA retroactively “grandfathered” New Horizons under its program umbrella. “With its mission plan and management structure already closely aligned to the program’s goals,” NASA explained in its January 2006 press kit, “New Horizons became the first New Frontiers mission when the program was established.”

As described by Dr. Stern, the New Horizons science team was formed from his original proposal team for the earlier Pluto Express Remote Sensing Investigation (PERSI), which might have flown aboard the ill-fated PKE mission. The Ball Aerospace-built PERSI—whose name also honored Percival Lowell, the Bostonian astronomer who searched fruitlessly for a trans-Neptunian planet at the turn of the 20th century—in its original form comprised six cameras, together with the Alice ultraviolet spectrometer and the Ralph multi-color imager and infrared imaging spectrometer. After the New Horizons science payload had been finalized in the early spring of 2001, it included PEPSI, together with the Radio Science Experiment (REX), the Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), and the Plasma and High-Energy Particle Spectrometer (PAM), the latter of which consisted of the Solar Wind at Pluto (SWAP) and Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI). Of these, PERSI and REX were termed the “core” payloads, with LORRI and PAM considered “supplementary” to add depth and breadth to the science-gathering. The mission concept call for a small flyby spacecraft, weighing about 880 pounds (400 kg) and carrying about 66 pounds (30 kg) of scientific instrumentation, and based in design upon the Comet Nucleur Tour (CONTOUR) spacecraft. The next stage was to propose a launch date, within the two-year JGA window of opportunity, and December 2004 was initially selected, tracking an arrival at the Pluto-Charon system in July 2012. A backup JGA opportunity also existed in the January 2006 timeframe.

In June 2001, NASA selected Dr. Esposito’s “Pluto and Outer Solar System Explorer (POSSE)” and Dr. Stern’s “New Horizons: Shedding Light on Frontier Worlds” proposals for a “Pluto-Kuiper Belt” (PKB) mission. “The President’s FY 2002 budget request does not contain development funding for a Pluto mission,” NASA explained at the time. “The Congress requested that NASA not do anything precipitous which would preclude the ability to develop a Pluto-Kuiper mission until the Congress could consider it in the context of the FY 2002 budget.” It was noted that, if accepted and developed, launch of the PKB mission would occur in the 2004-2006 timeframe, exploiting the JGA window of opportunity and permitting an arrival at Pluto “before 2020.” The two proposals were each granted $450,000 of NASA funding for a three-month concept study. “Both proposals are for complete missions, including launch vehicle, spacecraft and science instrument payload,” it was stressed. “Both address the major science objectives defined in the original announcement. Each proposal includes a remote sensing package that includes imaging instruments, a radio science investigation and other experiments to characterize the global geology and morphology of Pluto and Charon, map their surface composition and characterize Pluto’s neutral atmosphere and its escape rate.”

Unfortunately, the terrorist attacks in the United States on 11 September 2001, and the resulting stoppage of air traffic across the nation, caused a shutdown in government activities in central Washington, D.C., and the deadline for the final submission of the mission proposals was extended until the end of the month. Following oral briefings in October, NASA selected Dr. Stern’s New Horizons in November 2001 for a Phase B Preliminary Design Study, the conditions of which required passage through a confirmation review to address significant risks of schedule and technical milestones and regulatory approval for launch of the spacecraft’s nuclear power source, together with the availability of funding. “Congress provided $30 million in FY 2002 to initiate PKB spacecraft and science instrument development and launch vehicle procurement,” NASA explained. “However, no funding for subsequent years is included in the Administration’s budget plan.” In acknowledging the selection of New Horizons, Dr. Weiler pointed out that both proposals were outstanding, but Dr. Stern’s mission “represented the best science at Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, as well as the best plan to bring the spacecraft to the launch pad on time and within budget.”

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » New Horizons »

Great discussion of the history of this mission. I am a freelance writer and amateur astronomer and cover New Horizons for the website “Spaceflight Insider.” I also have run a blog opposing the controversial IAU demotion of Pluto for almost nine years and have published many articles on this topic. In 2008, I attended the Great Planet Debate at JHUAPL and in 2013, I attended the Pluto Science Conference at the same location. This July, I will be there once again for the flyby. If there is any way I can be of assistance in your upcoming discussion of the controversial IAU demotion, reaction to it by the media and public, and attempt to override/overturn/ignore it, please feel free to contact me. It is an exciting time for Pluto lovers!