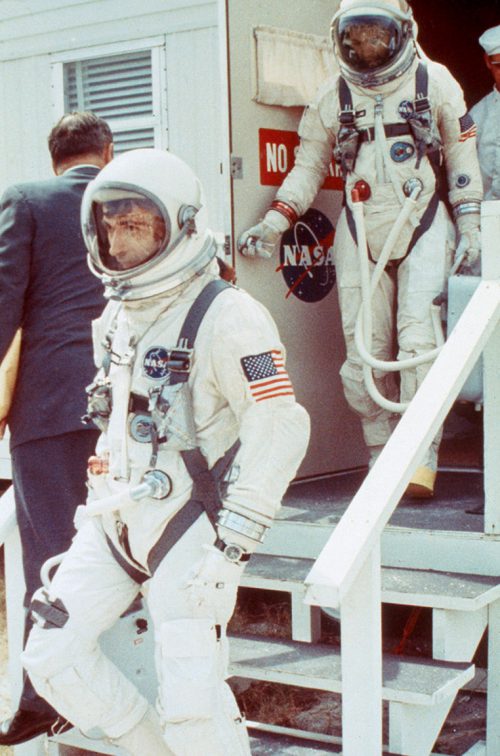

Fifty years ago, next week, a man who described himself as “nothing special” and “frequently ineffectual” became the first son of Earth to embark on as many as two spacewalks. Mike Collins—later to earn worldwide recognition as Command Module Pilot (CMP) on the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission—also became the first person to physically touch another vehicle in space. Unfortunately, he also became the first spacewalker to bring home absolutely no photographic record of his achievement. In July 1966, Collins and Gemini X Command Pilot John Young spent almost three days in orbit, rose to a peak apogee of 474 miles (763 km) above the Home Planet, and became the first crew to accomplish rendezvous with two separate spacecraft.

The two men were brought together as a team in January 1966, just a few weeks after wrapping up respective stints on other crews: Young as backup pilot of Gemini VI-A, Collins as backup pilot of Gemini VII. The pair were polar opposites—Young very publicity-shy and reserved, Collins gregarious and articulate—but both shared the tenet of being obsessive hard-workers and totally dedicated to the mission. During his spell on the Gemini VII backup crew, Collins had been teamed with veteran astronaut Ed White, whose career path carried him instead into Project Apollo and the coveted seat of Senior Pilot on the new spacecraft’s maiden voyage. “I would miss Ed,” admitted Collins in his autobiography, Carrying the Fire, “but I liked John and, besides, I would have flown by myself or with a kangaroo. I just wanted to fly.”

And fly they would. For Gemini X, more than any other mission before it, would launch on precisely the date scheduled at the time of the crew’s appointment, six months earlier. The only change came in mid-March, when their original backup crew of Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin were replaced—having been advanced to Gemini IX-A backup crew, following the deaths of Elliot See and Charlie Bassett—with “rookie” astronauts Al Bean and Clifton “C.C.” Williams. Even the preparations of Gemini X’s Titan II booster ran crisply; the only problem of note was the need to replace its second-stage fuel tank when a leaking battery caused some corrosion to its dome. Concurrently, Young and Collins’ Gemini-Agena Target Vehicle (tail-numbered “GATV-5005”) was prepared for flight, atop an Atlas rocket, and the astronauts found themselves shifting their sleep schedules to accommodate the critical timing for the two launches and their rendezvous. “For the last couple of days,” Collins wrote in Carrying the Fire, “we were staying up until 3 or 4 a.m. and sleeping until noon. Granted, we were staying up studying, but somehow the late hours carried with them a connotation of leisure and relaxation.”

Around noon EDT on 18 July 1966, Young and Collins were awakened and GATV-5005 was launched from Cape Kennedy’s Pad 14 on-time at 3:39 p.m. EDT, just two seconds late. It was followed by Gemini X, from neighboring Pad 19, at 5:20 p.m. Ascent was smooth, but the staging of the Titan II’s first and second stages provided a momentary concern for spectators on the ground, for it appeared to have exploded. “An instant after the two stages separated,” wrote Collins, “the first stage oxidizer tank ruptured explosively, spraying debris in all directions with dramatic, if harmless, visual effect.” Comically, Capcom Gordon Cooper mistakenly opened the ground communications link, allowing Young and Collins to overhear him summoning launch personnel to a debriefing in the ready room. Collins radioed that he and Young were otherwise engaged and unable to attend.

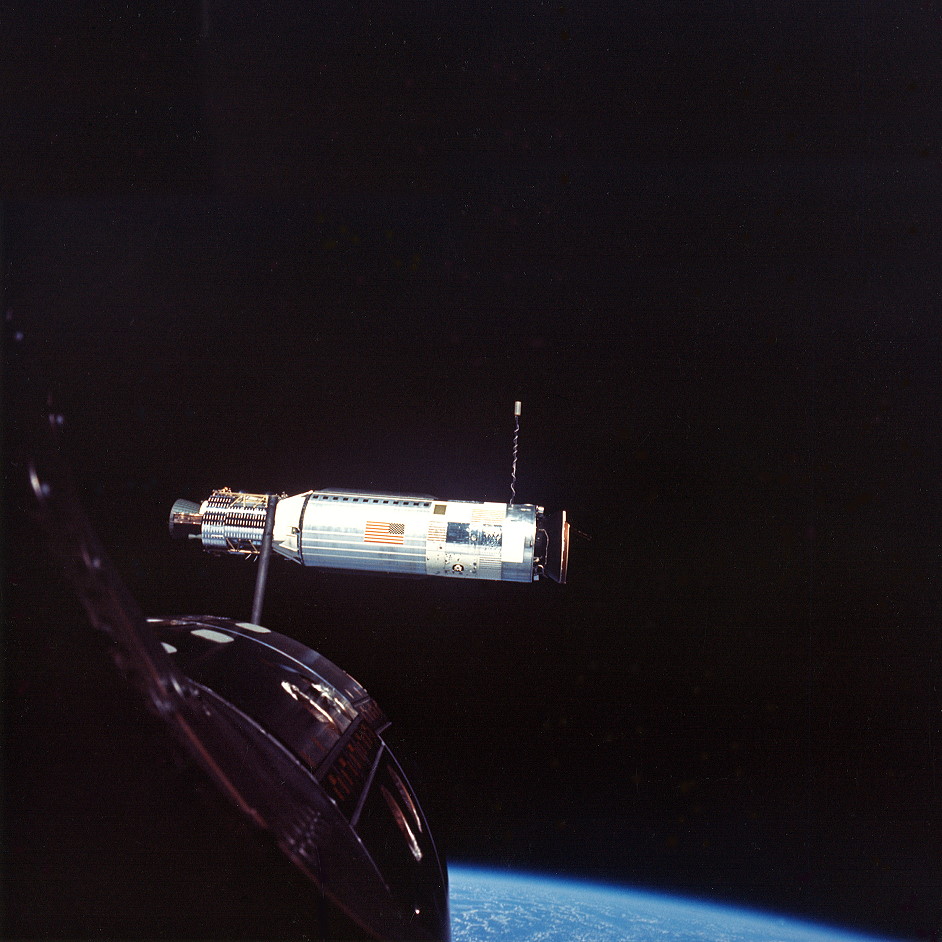

Rendezvous, of course, had been accomplished by several previous crews, most recently by Gemini IX-A astronauts Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan in June 1966. And before them, the Gemini VIII crew of Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott had rendezvoused and—for the first time—physically docked with the GATV-5003 Agena target vehicle in March 1966. However, the latter duo had suffered from a stuck-on thruster aboard their Gemini, which forced them to abandon docked operations and perform an emergency return to Earth. GATV-5003 remained in orbit and, though dead by the time of Young and Collins’ launch, was to be used as a rendezvous target, after docking with their own GATV-5005. The plan called for Gemini X to dock with GATV-5005 on its fourth orbit, about six hours after liftoff, after which an “optical” rendezvous with GATV-5003 would be attempted on the third day of the mission.

“We were going to be navigational guinea pigs,” wrote Collins, “and were going to compute on-board our spacecraft all the maneuvers necessary to find and catch our first Agena, instead of using ground-computed instructions to get us within range of our own radar.” To help them, Gemini X had an expanded computer memory, known as “Module VI,” which required Collins to use a portable sextant to measure angles between target stars and Earth’s horizon. “Combining Module VI data with a variety of charts and graphs carried on-board,” he continued, “we would be able to determine our orbit and predict where we would be at a given future time relative to our Agena target.”

Accomplishing all of their tasks—rendezvous with both Agenas, docking with one of them, together with spacewalking and a plate of research experiments—would be difficult to fit into three days and Young tried to press for extending Gemini X to its consumables limit of four days. However, Charles Mathews, manager of the Gemini Program Office, rejected the request. Young had two main concerns. First was the issue of whether he could slow Gemini X and GATV-5005 sufficiently to avoid hitting GATV-5003. Secondly was the very real concern that he might be unable to find Armstrong and Scott’s dead Agena using only Gemini X’s on-board optical equipment. “The problem with an optical rendezvous is that you can’t tell how far away you are from the target,” Young recalled later. “With the kind of velocities we were talking about, you couldn’t really tell at certain ranges whether you were opening or closing.”

Shortly after reaching orbit on the afternoon of 18 July 1966, Collins unstowed a Kollsman sextant and set to work on the lengthy optical navigation procedure, as Young maneuvred Gemini X into position to begin its chase of GATV-5005. Early troubles with their optical navigation tools prompted Mission Control to advise them to instead utilize ground computations. Unfortunately, an out-of-plane error and ultimately successful efforts by Young to get back on track left Gemini X depleted on its propellant reserves. He successfully accomplished a docking with GATV-5005 at 11:13 p.m. EDT, five hours and 53 minutes after leaving Cape Kennedy, but at the expense of burning three times as much propellant as his predecessors and leaving only 36 percent in reserve.

This excessive usage, which was not Young’s fault, but rather stemmed from a ground error in loading the Gemini X inertial guidance program, forced mission managers to scrap plans for the astronauts to undock, re-rendezvous, and re-dock with GATV-5005. Instead, they were instructed to press ahead with plans to rendezvous with GATV-5003. Their Agena’s main engine was ignited and increased their combined velocity by 260 mph (420 km/h). Armstrong and Scott, of course, had intended to burn GATV-5003’s main engine in March 1966, but their problems had forced them to abandon the test. As a result, Gemini X was the first-ever “space switch.”

“The sensation I got was that there was a pop, then there was a big explosion and a clang,” recalled Young. “We were thrown forward in the seats. Fire and sparks started coming out of the back end of that rascal. The light was something fierce and the acceleration was pretty good.” Interestingly, since the Gemini and the Agena were docked nose-to-nose, the firing propelled Young and Collins “backwards,” producing so-called “eyeballs-out” acceleration forces, as opposed to the “eyeballs-in” experienced when launching from Earth. Comparing the effect, Young likened it to riding the afterburner of a J-57 engine aboard the F-8 Crusader aircraft, whilst Collins drew parallels with his days flying the F-100 Super Sabre.

The burn effectively increased the apogee of Gemini X’s orbit to 474 miles (763 km), far higher than any previous manned spacecraft, and far higher than the 294 miles (473 km) of then-record-holders, Voskhod-2 cosmonauts Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov. This altitude allowed Young and Collins to discern the very obvious curvature of Earth. Using GATV-5005 also marked the first occasion that a piloted space vehicle had employed the propulsion assets of another to power its own flight. Yet even with these accomplishments achieved, the three-day mission of Gemini X remained only a few hours old. Ahead lay a second rendezvous, a pair of spacewalks … and the question of why Young and Collins’ mission remains the only known U.S. spaceflight which returned no imagery from its EVAs.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace