On the afternoon of 20 February 1962, millions of Americans listened and watched, transfixed as their countryman, John Glenn, plummeted back to Earth after completing three orbits of Earth. As detailed in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, it was a triumphant mission, but was also laced with drama, for worrisome indications had arisen that the heat shield and landing bag of his Friendship 7 capsule might not be locked into position. If the critical heat shield was loose, it was feared that Glenn would burn alive as he re-entered the atmosphere, and for this reason he had been instructed to keep his retrorocket package—which covered the heat shield during the early stages of descent—attached until he was through the worst of the heating. And if the heat shield was loose, only the retro package and its three metal straps had any chance of saving America’s newest hero from a fiery fate.

Throughout the early stages of re-entry, Glenn and Capcom Wally Schirra chatted like a pair of tourists exchanging travel notes, as Friendship 7 came within sight of El Centro and the Imperial Valley, followed by southern California’s Salton Sea. Then, as he passed over Corpus Christi, Glenn was told again, with evident urgency, to “leave the retro package on through the entire re-entry”. This meant that he would have to override the 0.05 G switch—which sensed atmospheric resistance and started the capsule’s re-entry program—and manually retract the periscope. Glancing at the on-board clock, which had ticked off four hours and 38 minutes since his 9:47 a.m. EST launch, his suspicions resurfaced that the reason for keeping the retro package on throughout re-entry was because the heat shield had indeed somehow become loosened.

Glenn would later admit to irritation at being kept in the dark about the potentially brewing disaster. Information about his spacecraft was his lifeblood, he wrote in his post-flight report, and it was knowledge, not absence of knowledge, which informed each of his decisions. Despite asking for Mercury Control’s reasons for wanting the package kept in place, he was told only that the decision was “the judgement of Cape Flight”. In Florida, Capcom Al Shepard gave Glenn as much information as he had. “We’re not sure whether or not your landing bag has deployed,” he said. “We feel it is possible to re-enter with the retro package on. We see no difficulty at this time with this type of re-entry.”

Although the package and its straps would eventually burn up as Friendship 7 plunged deeper into the atmosphere, Glenn assumed that, by keeping it on, the capsule might be protected for long enough until the thickening air would hold the heat shield against Friendship 7’s base. Max Faget, the father of the Mercury spacecraft, agreed with the plan of using the retro package to hold the heat shield in place, but admitted that it posed its own risks: any unused solid fuel could explode when re-entry temperatures grew too high, destroying the capsule. Flight Director Chris Kraft was also concerned that the attached retro package could cause Friendship 7 to tumble, incinerating both it and Glenn. Kraft, although eventually persuaded by Faget and Mercury Operations Director Walt Williams, strongly felt that the “cure” could be worse than the “disease”.

As the main phase of re-entry got underway, Glenn switched Friendship 7 from manual to fly-by-wire control, placing the capsule in a slow spin to hold it onto its correct flight path through the atmosphere. Just behind his back, the base of the spacecraft steadily heated to a maximum of 5,200 Celsius (9,400 Fahrenheit). Its ionized envelope of heat also blacked out communications, as Al Shepard’s voice in Glenn’s headset faded to nothing.

A thud reverberated through Friendship 7 as the retrorocket package’s three metal straps melted, a fragment of which “fell against the window, clung for a moment, and burned away”. Glenn would recount years later that he expected, as each second passed, to feel the heat on his back and along his spine, but continued working his procedures, as flaming bits of “something” streamed past the window. He had no idea if they were pieces of the retrorocket package or, indeed, of the heat shield.

He was preoccupied for much of the re-entry with damping out the capsule’s oscillations with the hand controller, but had the brief opportunity to glance through the window and see the sky turn to a bright orange, which he described to the automatic tape recorder as “a real fireball outside”. Every few seconds throughout the blackout, he attempted to contact Shepard, all the while working to keep Friendship 7 on the straight and narrow. At length, and by now through the worst of the re-entry heating, he heard the crackle of Shepard’s voice over his headset. The relief on the ground was audible.

Descending at subsonic speeds, Glenn felt the capsule rocking wildly and, as he looked upwards, could see “the twisting corkscrew contrail of my path”. Five miles above the Atlantic, the stabilizing drogue chute deployed automatically, followed by the main canopy a few seconds later. Shortly before splashdown, Glenn flipped the landing bag deployment switch. As expected, it lit up. Green. Subsequent investigation would discover that the rotary switch to be actuated by the heat shield deployment had a loose stem, which caused the electrical contact to break when the stem was moved up and down. This was believed to account for the false landing bag deployment signal. However, thinking back over the decision to keep the retro package attached throughout re-entry, Flight Director Chris Kraft would resolve never to agree to such a dangerous exercise again.

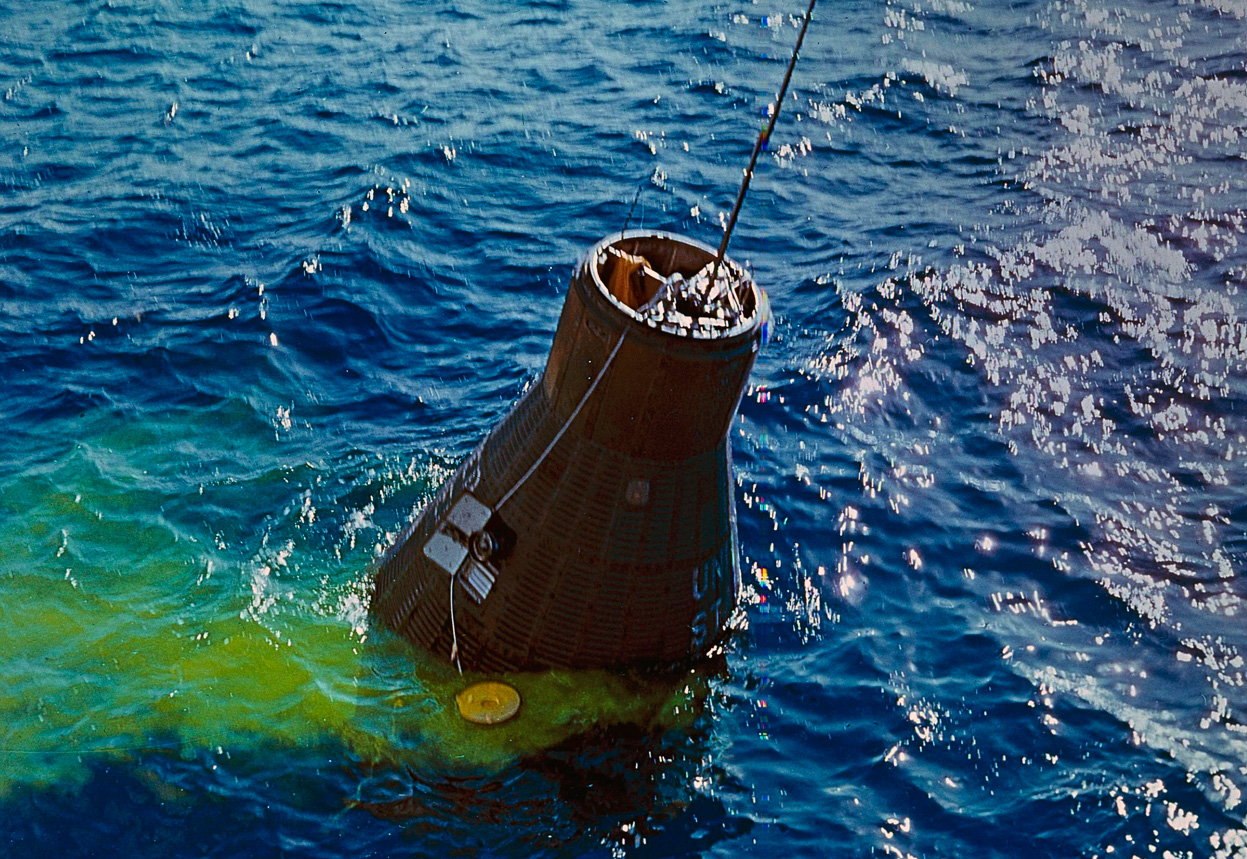

Glenn splashed down with what he later described as “a good solid thump” at 2:43 p.m. EST. His landing co-ordinates were later given as 21 degrees 20 minutes North and 68 degrees 40 minutes West, some 200 miles (320 km) northwest of Puerto Rico. He was 45 miles (72 km) off-target, a discrepancy caused by retrofire calculations which had not taken into account Friendship 7’s weight loss in consumables, but he was home safely. Seventeen minutes later, the destroyer USS Noa, codenamed “Steelhead”, drew alongside the capsule, followed by helicopters from the USS Randolph.

“I could hear gurgling sounds almost immediately,” Glenn said of his first few seconds back on Earth. “After it listed over to the right and then to the left, the capsule righted itself and I could find no traces of any leaks.” He released his straps and shoulder harness, removed his helmet, and put up his neck dam. He was sweating profusely, as physicians would later determine, and despite the open snorkels in Friendship 7’s hull, the humid air offered little respite. When the Noa arrived, he glanced through the window—coated with a smoky film from re-entry—and saw a deck full of sailors, so high in number that he asked the destroyer’s captain if anyone was actually running the ship!

Within minutes, Friendship 7 had been winched aboard and, after obtaining clearance from the bridge, Glenn detonated the hatch. He received two skinned knuckles, through his pressure suit gloves, as the plunger snapped back.

According to physicians Robert Mulin and Gene McIver, Glenn was fatigued, sweating and dehydrated; his only water intake had been from the apple sauce pouch, although his urine collector was full. After drinking water and showering, he became more talkative. He debriefed into a tape recorder aboard the Noa, before being flown to the Randolph for X-rays and an electrocardiogram and, later that evening, to Grand Turk Island for a welcoming committee of astronauts, physicians and NASA officials.

When asked by psychiatrist George Ruff if there had been any unusual activity during his mission, Glenn replied, “No … just a normal day in space!”

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 15th anniversary of STS-109, the last fully successful voyage by Space Shuttle Columbia.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

A Fine Story and I am Old enough to remember the Flight, I Had a Father, who served in the Navy in WW2, and really was a New Frontier Kind of Guy. Especially anything to due with Navy Ships & Space-Crafts. Thanks to Men Like My Dad & John Glenn and the rest of the Mercury Astronauts, I didn’t want for Role Models..

To The Great Men and Women in NASA, Thank You,

Dave Paquette