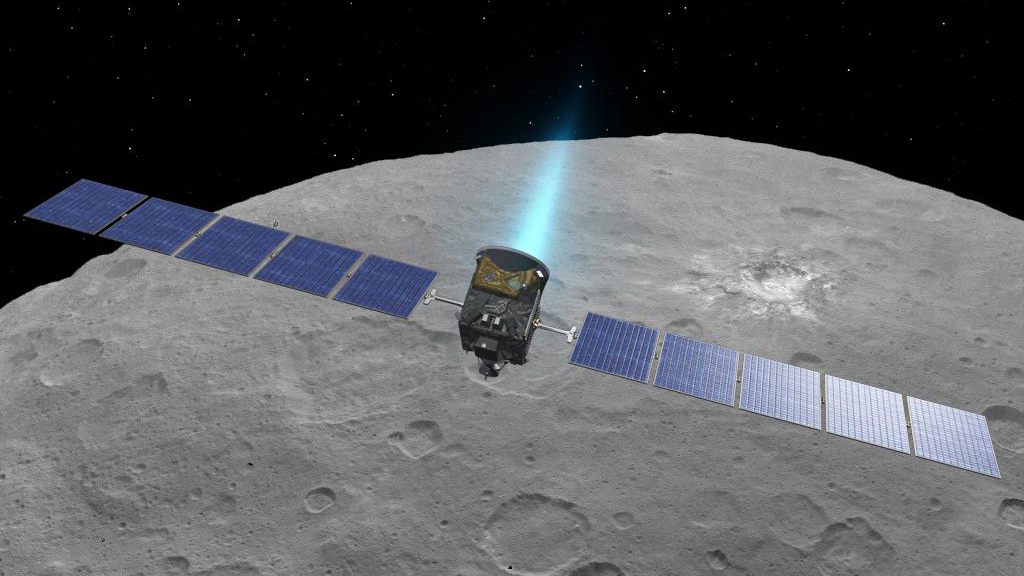

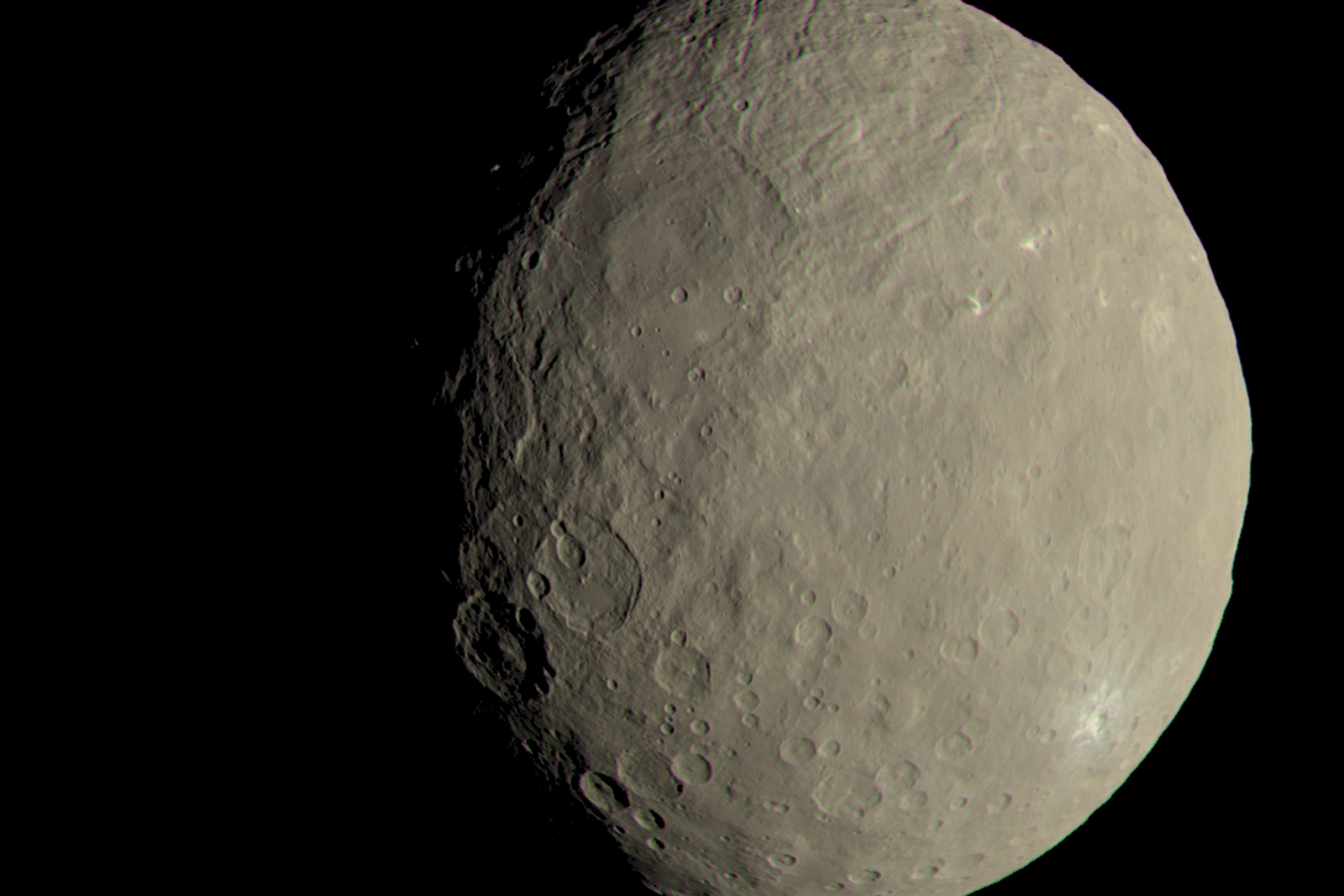

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has been orbiting the dwarf planet Ceres since March 2015, providing the first close-up views of this rocky and icy world residing in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Now, NASA announced that the mission will be extended, for the second time now. This is great news, partly because Dawn will be able to orbit closer to Ceres than it ever did before.

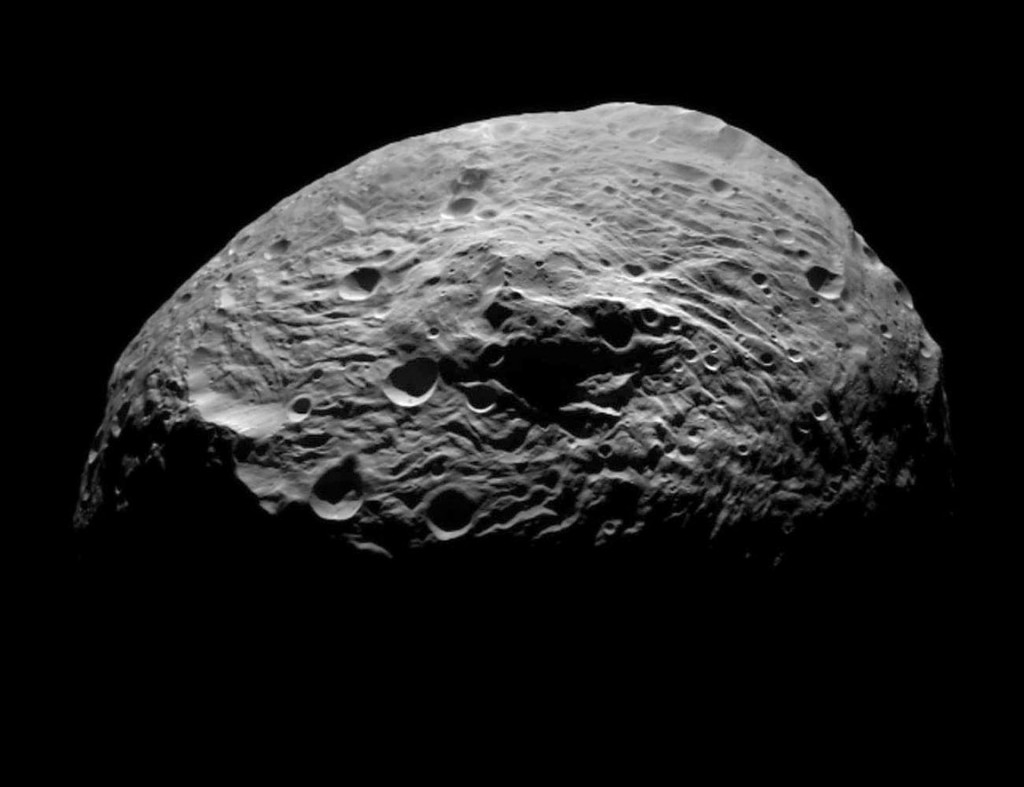

Dawn was the first spacecraft to orbit two different bodies in the Solar System, first the asteroid Vesta for 14 months from 2011 to 2012, and now Ceres since 2015. The voyage to both Vesta and Ceres was not an easy one, as reported recently, but it was absolutely worthwhile. There had been some discussion of possibly having Dawn go to a third target, the asteroid Adeona, but the first mission extension last year meant it would remain at Ceres until its fuel eventually runs out.

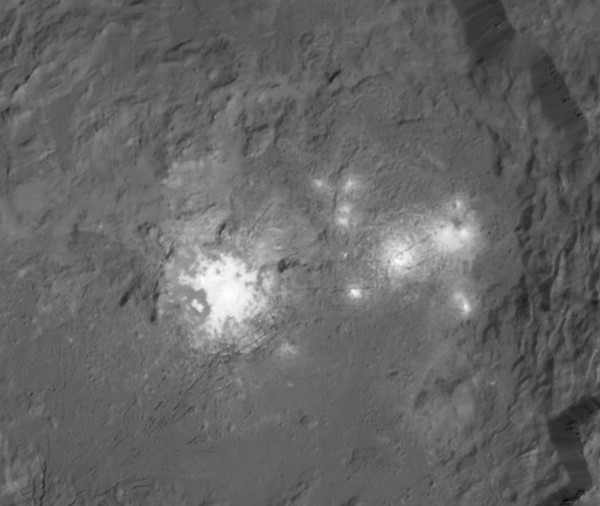

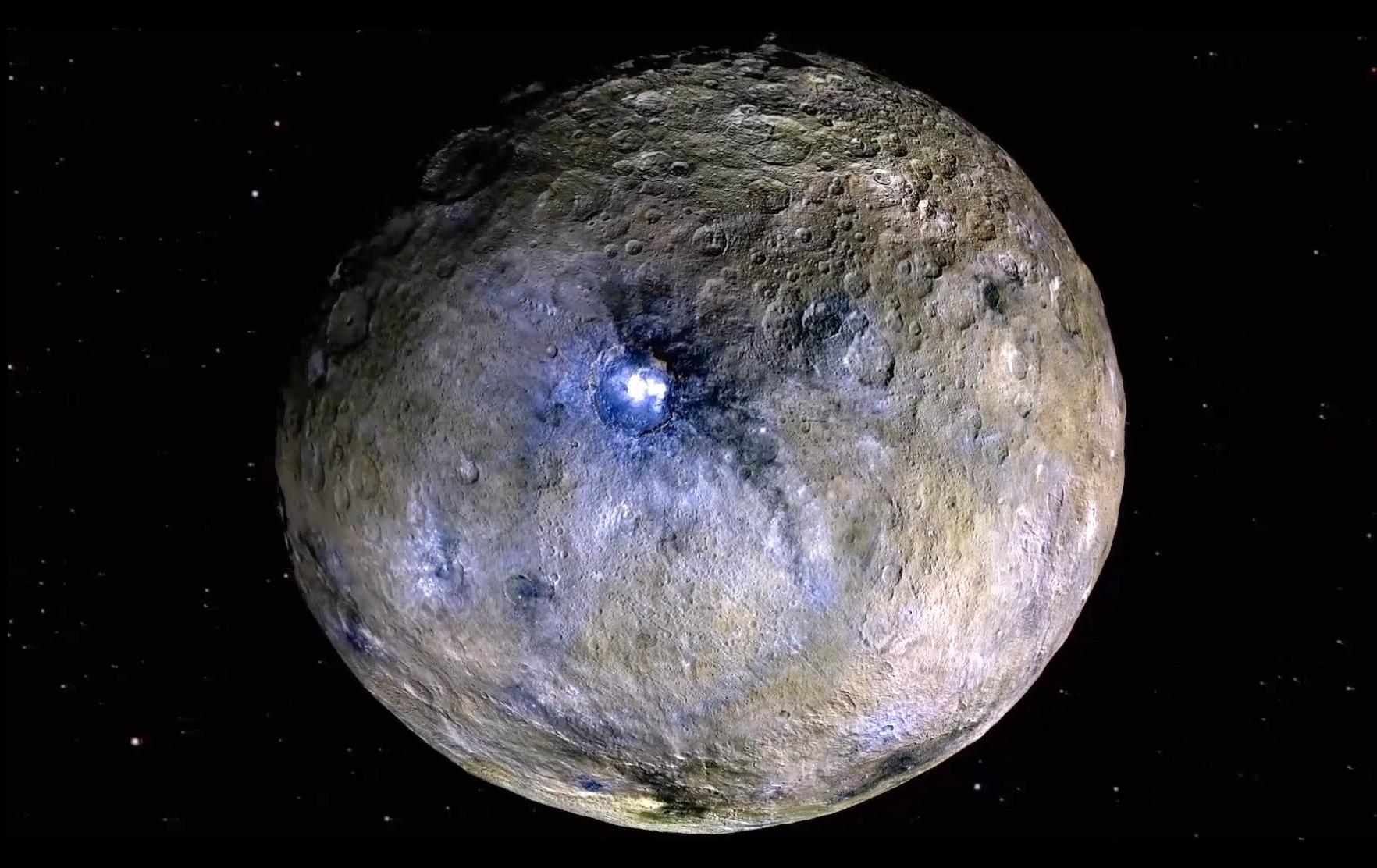

In the new extension, Dawn will be placed in an elliptical orbit which can bring the spacecraft to within 120 miles (200 kilometers) of the surface. This would of course allow for even higher resolution images to be taken than before, especially of features such as the unusual bright spots, which scientists think are salt deposits, perhaps left over from evaporating water. The closest that Dawn had orbited Ceres previously was 240 miles (385 kilometers).

Another objective will be to use Dawn’s gamma ray and neutron spectrometer to study the surface and determine how much ice there is in Ceres’ uppermost surface layer. Dawn will also measure Ceres’ mineralogy with its visible and infrared mapping spectrometer.

During the mission extension, Ceres will also reach perihelion, when it is closest to the Sun, in April 2018. It is at this time when scientists hope to detect water vapor coming from Ceres’ surface.

Unlike the Cassini probe, which plunged, on purpose, into Saturn’s atmosphere at the end of its mission last month, Dawn will remain in orbit after its fuel runs out, sometime in the second half of 2018, in order to prevent contamination of the surface.

Scientists had previously observed that the bright spots appear to change in brightness from day to night, evidence of ongoing geological activity inside Ceres. The brightest and most well-known spots are in Occator crater, but over 130 have been found so far. Dawn has also seen haze above the bright spots and found organic material on the surface.

According to Chris Russell, principal investigator of the Dawn mission, as reported in Gizmodo: “We believe this is a huge salt deposit. We know it’s not ice and we’re pretty sure it’s salt, but we don’t know exactly what salt at the present time.”

“The global nature of Ceres’ bright spots suggests that this world has a subsurface layer that contains briny water-ice,” said Andreas Nathues at Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany. He noted, however, that “The whole picture we do not have yet.”

The “Lonely Mountain” (aka Ahuna Mons) is another odd feature on Ceres, an isolated, oval-shaped hill, 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) tall, which sits at the edge of a crater with nothing else similar anywhere nearby. It may be a product of subsurface crypvolcanism, according to scientists.

Dawn has already shown us two worlds never seen up close before, and there is now more to come. As previously and accurately noted by Sarah Gavit of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) back in 2001, “Ceres and Vesta are two of the large unexplored worlds in our Solar System. We’ll learn about early planet formation in ways that wouldn’t have been possible before this mission.”

Bosses will not be truly on a timer. Struggle other gamers.