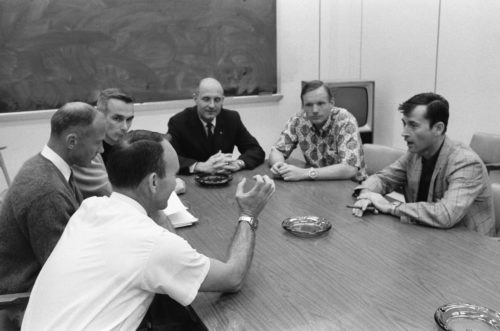

The Apollo 10 and 11 crews in discussion, after the completion of the Apollo 10 mission. Around the table from foreground are Apollo 11 Command Module Pilot (CMP) Mike Collins, Apollo 11 Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Buzz Aldrin, Apollo 10 LMP Gene Cernan, Apollo 10 Commander Tom Stafford, Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong and Apollo 10 CMP John Young. Photo Credit: NASA

Fifty years ago, this spring, the three astronauts of Apollo 10 circled the Moon, marking humanity’s second voyage to our closest celestial neighbor. Their spacecraft had many of the provisions needed to execute a landing—a Command and Service Module (CSM), which they had nicknamed “Charlie Brown”, and a Lunar Module (LM), “Snoopy”—but on this “F mission”, Commander Tom Stafford, Command Module Pilot (CMP) John Young and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Gene Cernan performed a full dress rehearsal for the first landfall on alien soil. They would test the LM’s descent engine, guidance and navigation systems and radar and in doing so would clear the final hurdle in anticipation of the historic Apollo 11 voyage in July.

READ AmericaSpace’s first three parts of this Apollo 10 50th anniversary feature:

Part 1: https://www.americaspace.com/2019/05/19/to-simply-land-remembering-apollo-10-50-years-on-part-1/

Part 3: https://www.americaspace.com/2019/06/02/we-have-arrived-remembering-apollo-10-50-years-on-part-3/

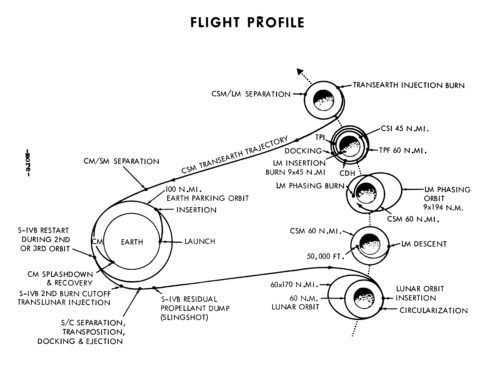

Apollo 10 flight profile. Image Credit: NASA

In doing so, they would come face to face with the immense risk that they were taking and would depart the Moon fully aware that the journey was fraught with danger and complexity. High above the Moon, Stafford and Cernan shimmied through the short tunnel from Charlie Brown into Snoopy. Their day began with an irritating problem with a radar gauge, then a communications difficulty and later an error with the lunar module’s gyroscopic stabilization platform. Precisely on schedule, Apollo 10 disappeared behind the Moon on its 12th orbit and, when the radio blackout ended 40 minutes later, Stafford jubilantly announced that Charlie Brown and Snoopy had successfully parted company. After the undocking at 2:00 EDT, Young used his thrusters to withdraw from the lander.

“You’ll never know how big this thing gets when there ain’t nobody in here but one guy,” he drawled.

“You’ll never know how small it looks when you’re as far away as we are!” countered Cernan.

“Yeah,” continued Stafford. “Don’t get lonesome out there, John.”

Commanded by Tom Stafford (center), the Apollo 10 crew included future Moonwalkers John Young (right) and Gene Cernan (left). Photo Credit: NASA

As the range opened, it was Young’s task to activate a homing receiver for the lander’s rendezvous radar, and he had to toggle a switch several times to make it work properly. Then a glitch with the orientation of Snoopy’s antennas affected communications with Charlie Brown. Next, the link between Charlie Brown and Houston fell silent. “A quick check of the system,” wrote Stafford in his memoir, We Have Capture, “showed that a breakdown had occurred in the line between Houston and the tracking station in Goldstone, California.” At length, the problems ironed out. For the next eight hours, Young would score a new record: the first man to fly solo in lunar orbit.

Somewhere behind the Moon, during the first of Snoopy’s four independent orbits, Stafford fired the descent engine for the first time to reduce its velocity and begin dropping toward the lunar surface. He started the engine at its minimum thrust level—first 10 percent, waited for a few seconds, then opened the throttle to 40 percent—and, from his vantage point, John Young reported that they were moving noticeably away from him. For the men aboard the lander, on the other hand, the ride seemed relatively slow and established Snoopy in an elliptical orbit with a “perilune” of nine miles (15.4 km) above the surface. The two astronauts, broadcasting on “hot-mike” to the whole world, were exultant.

“We is down among ’em, Charlie!” radioed Cernan.

“Rog, I hear you’re weaving your way up the freeway,” replied fellow astronaut Charlie Duke, the capcom in Mission Control.

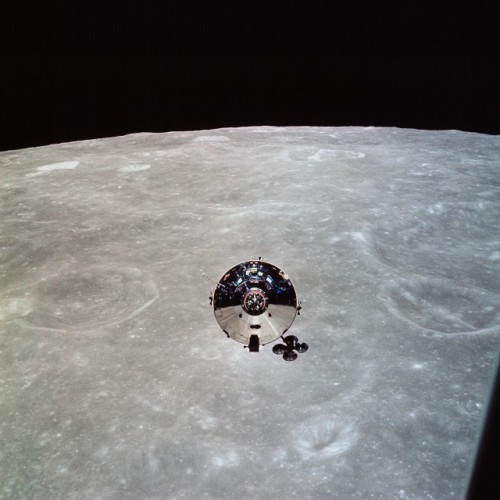

As Command Module Pilot (CMP) of Apollo 10, John Young became the first human being to fly solo in orbit around another celestial body. Photo Credit: NASA

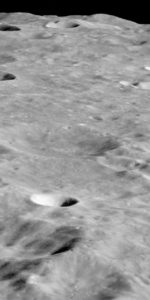

Twelve miles (20 km) above the Moon, as intended and precisely on cue, the radar detected the looming surface and began feeding rate-of-descent and altitude data into Snoopy’s computer. The lunar mountains, rushing past below, seemed almost close enough to touch, their appearance and texture resembling wet clay. As they approached Mare Tranquillitatis—an area targeted for the first landing, running along an imaginary “lane” of physiographic features memorized from months of studying maps and charts—the men were astonished by the barrenness of the terrain. “There are enough boulders around here,” Stafford breathed, “to fill up Galveston Bay.”

Since their assignment to the mission the previous November, Stafford and Cernan had spent hundreds of hours poring over maps and photographs from the unmanned Lunar Orbiters of two of the candidate landing sites for Apollo 11. Both lay in the relatively flat Tranquillitatis region and the men had even tried to simulate part of their trajectory aboard a T-38 aircraft back on Earth. When the time came to fly over the favoured landing spot, “Site 2”, for real, they knew the craters, mountains, rilles, bumps, hollows and furrows so well that they literally formed a familiar “road”, guiding them to the landing zone. To their eyes, it was a virtual lunar highway and they had nicknamed it “U.S. 1”. Along the way, a range of low mountains was called the “Oklahoma Hills”, a rille which split into a pair of craters was dubbed “Diamondback” and “Sidewinder” and one ridge was even named in honor of Stafford’s then-wife, Faye.

Commander Tom Stafford, pictured during one of Apollo 10’s color telecasts. Photo Credit: NASA

Attempting to shoot a photograph every three seconds as Snoopy passed over Site 2, Stafford was annoyed when the “goddamn” Hasselblad camera issued an ominous puff of smoke and jammed. (He later apologized to Victor Hasselblad upon his return to Earth.) It was the first of a number of unfortunate outbursts from Snoopy’s cabin. Deprived of his camera, Stafford resorted to verbal reports, comparing the inhospitable appearance of the site to the high desert near Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. If Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were to find themselves heading for the “near” end of the target ellipse, then they would have a smooth landing; but he advised that a landing at the “far” end would demand additional fuel to find a spot free of boulders. Just beyond Tranquillitatis, and an hour after the first burn, Stafford again fired Snoopy’s descent engine, this time using full throttle to accelerate them by almost 125 mph (200 km/h) and enter an eccentric orbit that simulated an ascent from the surface.

When the time came to jettison the descent stage and return to redock with Young, Stafford oriented the vehicle correctly but noted a slight yaw rate on his attitude indicators. “Telemetry suggested we might have an electrical anomaly,” he wrote, “so I started to troubleshoot the problem.” Shortly thereafter, Cernan, thumbing through his checklist, switched control from the Primary Navigation, Guidance and Control System (PNGS) to the Abort Guidance System (AGS). The former provided an exact navigational reading, whereas the latter would “get us the hell out of there if unexpected trouble cropped up.”

In case Armstrong and Aldrin needed to abort in a hurry—punching their ascent stage away if their descent went awry—a test of the AGS in lunar orbit was critical. Stafford and Cernan had rehearsed it a hundred times in the simulator. Clad in their bulky suits, however, both men found it difficult to hit the right switches.

An instant after Cernan set the control mode of the AGS to “attitude hold”, Stafford reached across and inadvertently changed it to “auto”.

Snoopy’s ascent stage, pictured during final approach for docking, as seen by John Young from Charlie Brown’s windows. Photo Credit: NASA

Seconds later, they were ready to blow the four explosive bolts to separate the ascent stage from the descent stage and begin to trek back to Charlie Brown. Suddenly, and without warning, Snoopy went berserk, lurching wildly in both pitch and yaw axes. “Gimbal Lock!” shouted Stafford urgently, believing the lander’s gyros to have frozen. Cernan, over hot-mike and with the whole world listening in, yelled with unfortunate clarity: “Son-of-a-bitch! What the hell happened?” As the menacing lunar terrain, the black sky and the grim line of the horizon alternately flashed in Snoopy’s windows, both men knew they had just seconds to resolve whatever was wrong.

By activating the AGS and setting it to “auto”, Stafford had in effect instructed Snoopy’s radar to begin searching for Charlie Brown and the abort guidance system was now causing the lander to flip wildly around its center of mass. Quickly, he pushed the button to jettison the descent stage and steadily regained control of the gyrating ascent stage. Fearing that the inertial measurement unit was close to gimbal lock, Stafford executed a pitch maneuver, started working the attitude switches and finally calmed the ascent stage down. From Cernan’s initial shout to Stafford’s final report to Houston that Snoopy was back under control, three minutes elapsed.

Artistic visualization of the rendezvous operation between the Command and Service Module (CSM), Charlie Brown (foreground), and Lunar Module (LM), Snoopy (background). Image Credit: NASA

Those minutes were unnerving not only for Stafford and Cernan, but also for John Young, listening helplessly from Charlie Brown. “I don’t know what you guys are doing,” he drawled in his typically understated manner, “but knock it off. You’re scaring me!”

Years later, Cernan and Stafford would both say that it was a classic piloting error. “Neither Tom or I can be sure,” Cernan related in his autobiography, The Last Man on the Moon, “but when it came time to stage…there was some switch that had to be changed, and I changed it. And I’d be willing to bet that…I put the switch in the new position and Tom went ahead and moved it back to the old one. His action was to move the switch. I’d already done it for him. But he didn’t know that and, when he moved the switch, he just moved it back to where it was. In effect, we created the problem!”

Although the cause of the glitch was easily solvable in time for Apollo 11, the episode highlighted that nothing could be taken for granted on a lunar expedition. Charlie Duke, helpless to assist, had warned them from his data that they were close to gimbal lock, but things were moving far too quickly for him or anyone else in Mission Control to help. By contrast, the return to Charlie Brown was perfect; Stafford found Snoopy’s ascent stage a little difficult to hold steady, but Young had no problem docking and all three men were greeted by the welcome “ripple-bang” of a dozen capture latches snapping shut. “Snoopy and Charlie Brown are hugging each other,” chortled Stafford. A few minutes later, back in the command module, Young received a couple of hugs, too.

The Home Planet, as seen from a distance of 100,000 miles (160,000 km), during the Apollo 10 mission. Photo Credit: NASA

Several days later, on 26 May 1969, the Apollo 10 command module hit Earth’s atmosphere at a lunar-return velocity of close to 25,000 mph (40,000 km/h). Cernan remembered an enormous white-and-violet “ball” of flame, literally sweeping up the spacecraft like a glove. “It grew in intensity,” he wrote, “and flew out behind us like the train of a bride’s gown, stretching a hundred yards, then a thousand, then for miles…and the whole time we were being savagely slammed around inside the cabin.”

To some people, the fire and brimstone nature of re-entry illustrated God’s wrath with this foul-mouthed team of space flyers. One man who was not happy, was an over-zealous minister named Rev. Larry Poland. He was vocal in complaining that Stafford’s crew had taken “the language of the street” with them to the Moon, and urged them to apologize for their “profanity, vulgarity and blasphemy.” However, recognizing the reality that its men were in a life-or-death situation, NASA managers stood by the crew, saying they had “acted like human beings.” After splashdown, they were greeted with tongue-in-cheek notices, one of which read: The Flight of Apollo 10: For Adult Audiences Only. Bob Gilruth, the head of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas, had burst out laughing when he heard the swearing, and veteran flight director Chris Kraft was philosophical in his autobiography, Flight. “They were out there doing man’s work at the Moon,” Kraft wrote. “If a cuss word or three slipped out, well, who the hell cared anyway?”

The Apollo 10 command module descends to splashdown on 26 May 1969. Photo Credit: NASA

Larry Poland cared greatly and laughing it off was not good enough. In the days and weeks after the mission, hundreds of letters and telegrams flooded into NASA’s Washington, D.C., headquarters, some tolerating the language, others condemning it. John Young was not involved and Tom Stafford (famously nicknamed “Mumbles”) had uttered his profanities under his breath. Gene Cernan, though, was well and truly in Rev. Poland’s firing line. His words could neither be misconstrued or explained away. At a news conference, Cernan apologized to the people he had offended and thanked those who understood how he came to say what he did. Privately, though, he was furious. It made no difference, he wrote, that Poland accepted his apology and forgave him, for Cernan “never got around to forgiving that self-righteous prig!”

It was the only unfortunate incident to blight a mission which had otherwise proved enormously successful; by verifying the performance of the entire Apollo spacecraft in orbit around the Moon, Apollo 10 had cleared virtually every remaining hurdle in the path to the first lunar landing. By the start of June 1969, 50 years ago, this week, the first manned landing on alien soil was only weeks away.

An exceptional part series on the the Apollo 10 mission. Well-written and well-documented with interesting tidbits of I formation.