NASA’s long-awaited Lucy mission to conduct flyby explorations of multiple Trojan asteroids which either lead or trail the orbital path of giant Jupiter has been officially green-lighted to enter its Assembly, Test and Launch Operations (ATLO) phase, following last week’s successful conclusion of the Systems Integration Review (SIR). Selected alongside the Psyche asteroid mission in January 2017 as part of NASA’s low-cost Discovery Program, Lucy will begin a 12-year odyssey into deep space when it rises from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V booster in October 2021. And although many missions have flown past and even orbited multiple celestial targets, none will achieve as many encounters as Lucy.

The four-day SIR process, which wrapped up on 31 July with a virtual review by the Standing Review Board to the Lucy team, ensured that all segments, components and subsystems for the mission—whose Discovery Program parameters have cost-capped it at $450 million—are firmly on schedule ahead of integration. This includes the spacecraft’s three scientific instruments, which draw their design and engineering heritage from NASA’s New Horizons and OSIRIS-REx missions, together with its electrical, communications and navigational systems. In response to the ongoing dynamic nature of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, NASA and its industrial partners delayed construction of several of Lucy’s instruments and components that the ATLO team co-ordinated a new schedule to allow greater flexibility as this one-of-a-kind mission prepares to fly.

“No one anticipated that we would be building a spacecraft under these circumstances,” said Principal Investigator Hal Levison of Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colo., “but I once again have been impressed by this team’s creativity and resiliency to overcome any challenge placed before them.”

With the SIR now complete, ATLO activities will begin in earnest next month at prime contractor Lockheed Martin Space Systems in Littleton, Colo. It marks the latest milestone point for a mission which has taken almost six years to rise from a proposal to actual flight hardware. Named in honor of the famous Australopithecus afarensis hominin skeleton found in Ethiopia in November 1974, Lucy was submitted as a proposal in early 2015 following a Discovery Program announcement of opportunity the previous fall. In September of that year, it was picked as one of five finalists for in-depth conceptualization studies and finally, in January 2017, Lucy and another mission—the Psyche asteroid orbiter—were formally selected for flight. “This is what Discovery Program missions are all about,” said NASA Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate Thomas Zurbuchen, “boldly going to places we’ve never been to enable groundbreaking science.”

Designed to enable low-cost missions with a ceiling of about $450 million, the Discovery Program has seen 12 epic voyages of exploration since the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) Shoemaker, which launched way back in February 1996 and visited, orbited and eventually soft-landed on asteroid 433 Eros. Since then, other Discovery-class expeditions have included Mars Pathfinder and its Sojourner rover, the Mercury-bound MESSENGER orbiter and the Kepler observatory, together with a flotilla of spacecraft to examine the Moon, asteroids, the solar wind, comets and objects in the asteroid belt. Most recently, since November 2018, NASA’s InSight lander has resided on the surface of Mars, exploring the deep (and surprisingly active) interior of the Red Planet.

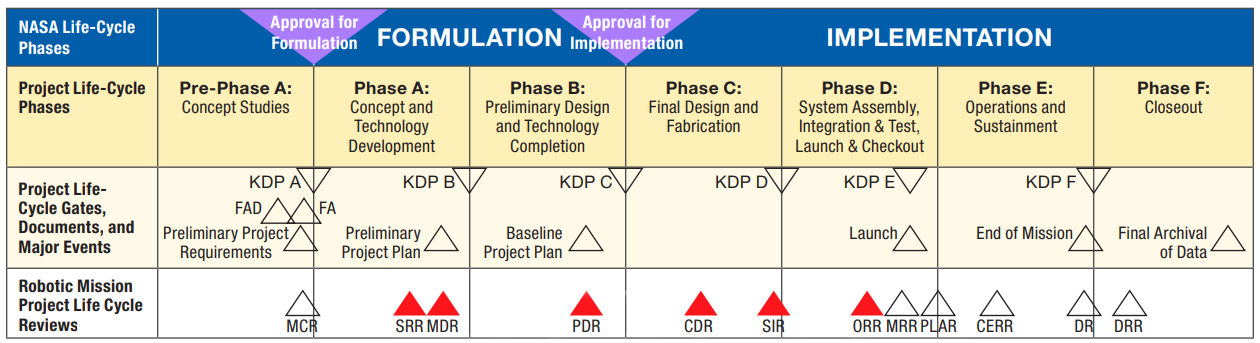

Last October, Lucy finished her Critical Design Review (CDR) milestone and in so doing ticked off her remaining technical obstacles, validated her mission architecture and permitted the onset of work to begin assembling her spacecraft “bus” and systems. Measuring over 45 feet (13 meter) between the extremities of her immense solar array “wings”, Lucy is equipped with three principal scientific instruments, upgraded versions of hardware previously utilized on the New Horizons and OSIRIS-REx missions.

These are a high-resolution visible imager from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) in Laurel, Md., a panchromatic and color visible imager from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Md., and a thermal infrared spectrometer from Arizona State University in Tempe, Ariz. All three—as well as Lucy’s high-gain antenna and terminal tracking camera—will be brought to bear on some of the most enigmatic objects in the known Solar System; objects which are so ancient that they may represent the primordial building-blocks of the planets themselves.

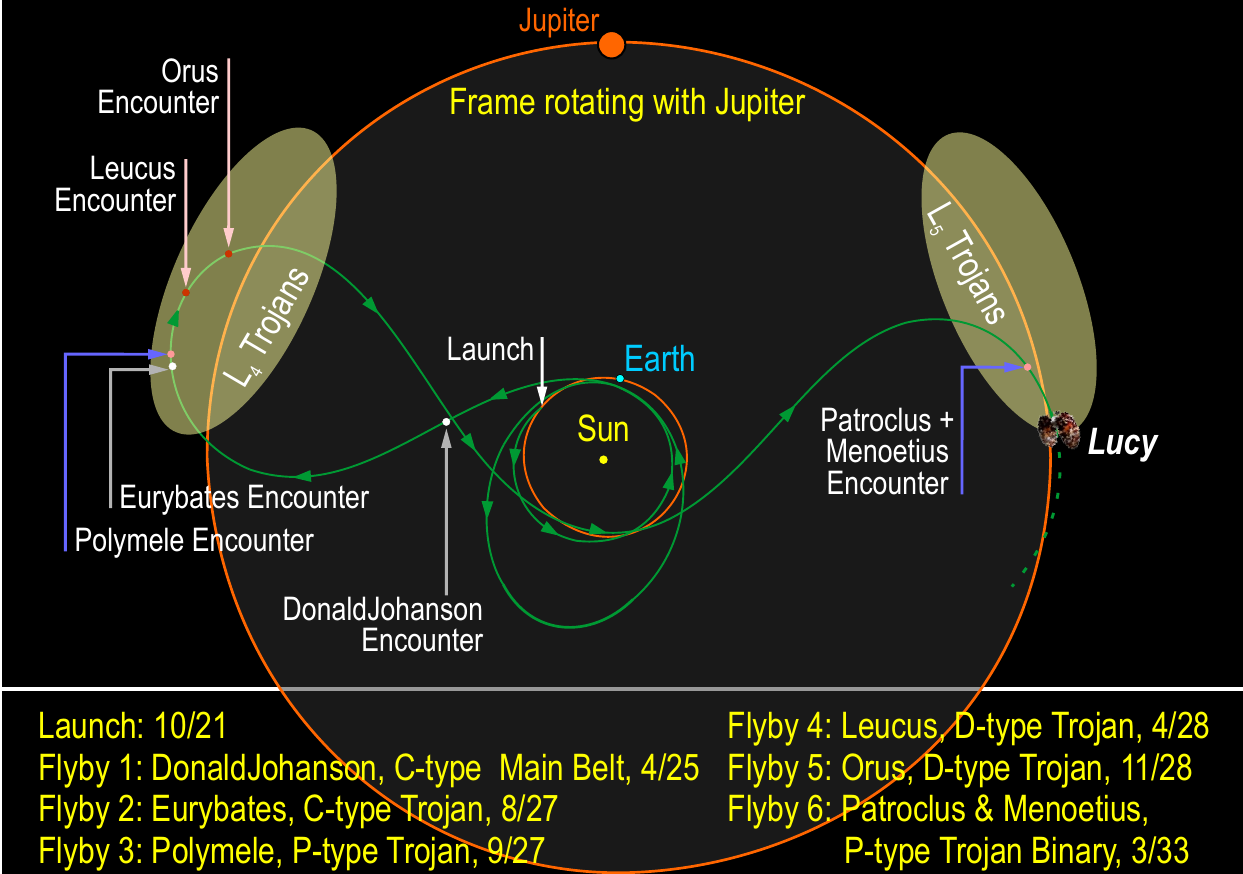

Early last year, ULA was selected to launch Lucy atop its workhorse Atlas V 401 booster from the Cape in the fall of 2021, at an estimated cost of $148.3 million. Described by ULA CEO Tory Bruno at the time as possessing “a once-in-a-lifetime planetary launch window”, the spacecraft’s voyage through the inner Solar System to the main asteroid belt and thence to the Trojan “swarms” which precess and trail Jupiter in its orbit promises to be one of the most complex challenges ever undertaken in celestial navigation.

Just as the remains of the australopithecine Lucy in Ethiopia ignited our fascination for our long-since-fossilized forebears, so her robotic namesake will explore these “fossils” of planetary evolution. They typically occupy stable orbits 60 degrees “ahead” or “behind” a larger planetary body at the gravitationally-balanced L4 or L5 Lagrange Points. And although thousands of Trojans are currently cataloged, and have been detected in the vicinity of Mars, Neptune and even Earth itself, the vast majority are associated with Jupiter. Named in honor of characters from the Greek and Trojan opposing sides of the Trojan War, they typically occupy a “Greek camp” at L4 (ahead of Jupiter) and a “Trojan camp” at L5 (trailing Jupiter).

However, one of Lucy’s targets—617 Patroclus, named for Achilles’ Greek companion—is one of two exceptions, named and assigned to the Trojan camp before this convention came into effect. It is believed that millions of Jovian Trojans exist, perhaps equal in number to the amount of small celestial bodies in the Mars-Jupiter asteroid belt.

Gravitationally trapped at L4 or L5 for billions of years, due to the combined tug of the Sun and Jupiter, these primordial bodies represent the leftovers of the building-blocks from the giant gaseous planets and their exploration by Lucy is expected to reveal new clues about our own origins.

Following launch during a three-week “window” which opens on 21 October of next year, Lucy will test its mettle ahead of its Trojan exploration campaign by surveying the “main belt” asteroid 52246 Donaldjohanson, situated some 220 million miles (350 million km) from the Sun and measuring only about 2.5 miles (4 km) across. Named for the selfsame palaeontologist who found the Lucy skeletal remains almost five decades ago, it is a relatively common C-type, or “carbonaceous” asteroid. The robotic Lucy will pass it at a distance of about 570 miles (920 km) on 20 April 2025. This will allow the team to demonstrate their spacecraft’s capabilities before the first encounter with a Trojan takes place on 12 August 2027.

First up are four members of the Trojan camp, led by 3548 Eurybates, which measures about 42 miles (68 km) across and earlier this year was verified by Hubble Space Telescope (HST) data to possess its own satellite. Six thousand times fainter than Eurybates itself, implying a diameter no greater than a half-mile (1 km), the satellite promises to be one of the smallest objects ever visited by a spacecraft.

This encounter will be followed up on 15 September 2027 when Lucy sweeps just 260 miles (415 km) past the tiny, reddish-colored 5094 Polymele, before heading to survey the mid-sized, slow-rotating 1351 Leucus on 18 April 2028 and the exceptionally dark 21900 Orus the following 11 November. With the completion of these four Trojan visits, the spacecraft’s trajectory will carry it back to Earth for a gravity-aided boost to send it onward to its final planned target: the “binary” Trojan 617 Patroclus, in the Greek camp, which it will encounter on 2 March 2033. Measuring about 70 miles (110 km) across, it has a companion, Menoetius, which is only 10 percent smaller than Patroclus. The two objects reside about 420 miles (680 km) apart.

Lucy’s instrumentation will conduct imaging of each of its asteroidal quarries, searching for traces of silicates, ices and carbonates and measuring their thermal spectral signatures and masses. And getting to each of them has proven to be a marvel of trajectory planning. “There are two ways to navigate a mission like Lucy,” said optimization technical lead Jacob Englander. “You can either burn an enormous amount of propellant and zigzag your way around, trying to find more targets, or you can look for an opportunity where they just all happen to line up perfectly. As such, Lucy’s high-speed lane-changes will be effected through gravity-assisted boosts, with minimal fuel usage.

Following selection in January 2017, Lucy progressed rapidly through Preliminary Design Review (PDR) and is presently in its final design and fabrication phase. Next month, at prime contractor Lockheed Martin’s facility in Littleton, Colo., assembly of the spacecraft will get underway in earnest. Launch will occur during a three-week period which opens on 21 October of next year, with a “short window” each day around 6 a.m. EDT. Missing the 2021 launch window will cause the mission to stand down for another year.

And although Lucy’s closest approaches to its primary targets—Donaldjohanson, Eurybates, Polymele, Leucus, Orus and Patroclus—are expected to be over in a matter of hours, the spacecraft itself will occupy an orbit that will likely remain stable for 600,000 years. Just like its prehistoric ancestor, the australopithecine Lucy, who walked the plains of Ethiopia around three million years ago, so her robotic descendent will wander the outer Solar System until, perhaps, someday, another human gets to see her again.