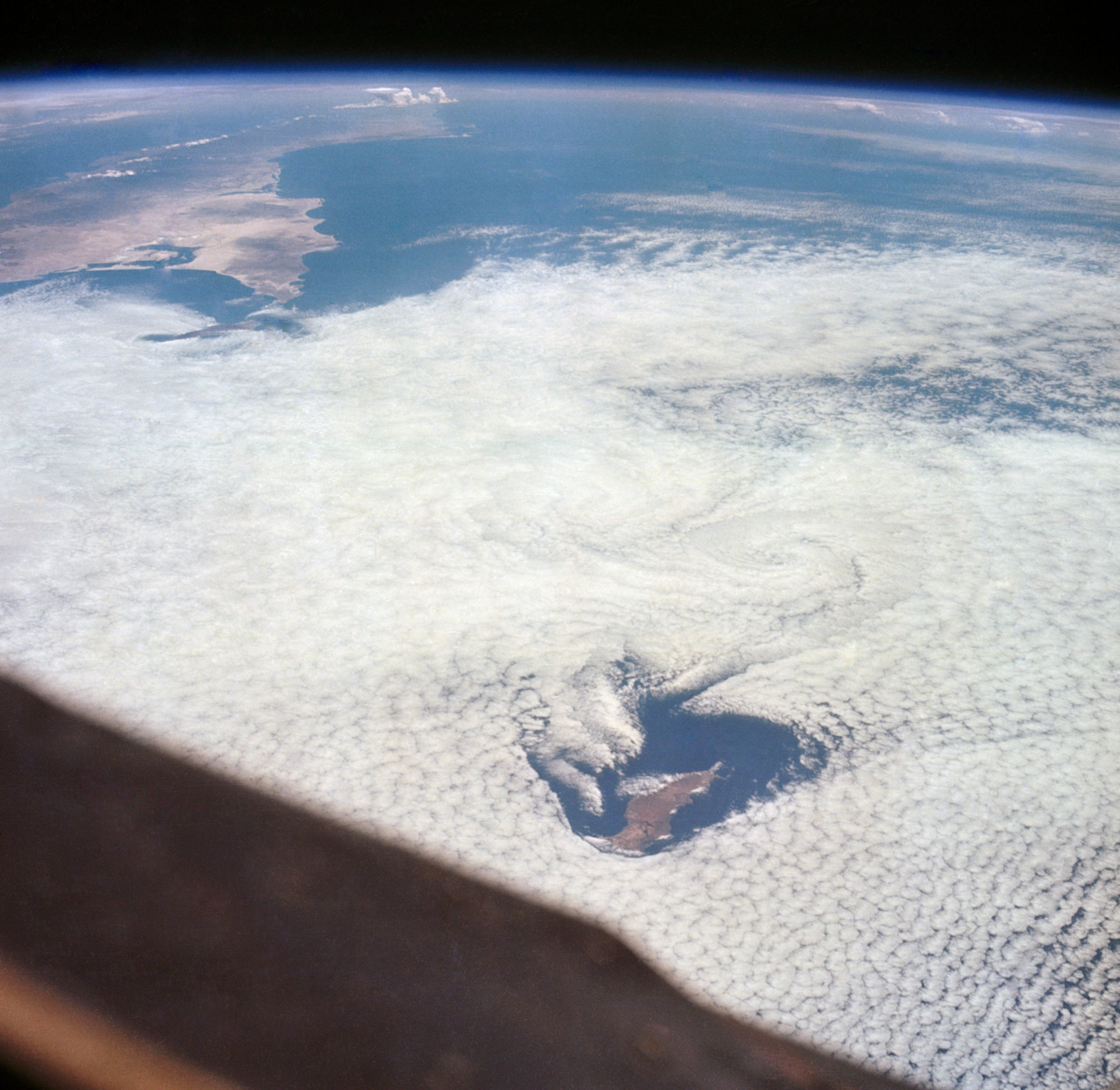

More than a half-century ago, America’s attention was laser-focused upon achieving bootprints on the surface of the Moon before the end of the 1960s. To accomplish that end, U.S. astronauts needed to demonstrate the capacity to remain in space for long durations, achieve rendezvous and docking and perform spacewalks. One of those goals—spending increasingly longer periods in space than ever before—was the central mission requirement of Gemini V crewmen Gordon Cooper and Charles “Pete” Conrad, who launched from Earth on this day in 1965. And for both of them, their record-breaking eight days in orbit would turn into a difficult, uncomfortable marathon.

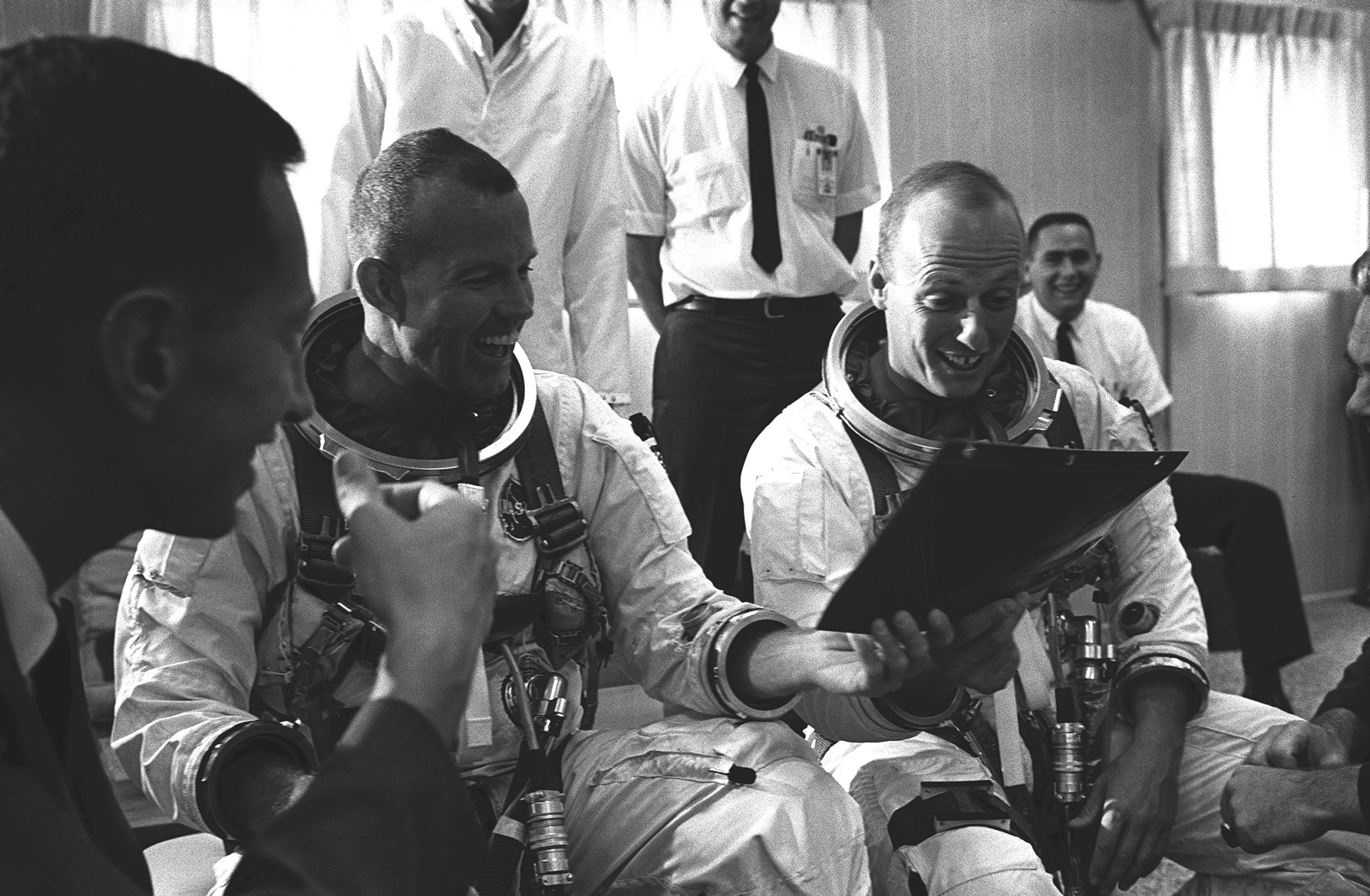

Durations of between eight and 14 days were expected to duplicate the “minimum” and “maximum” anticipated lengths of a return voyage to the Moon. And although Cooper and Conrad had lightheartedly (and semi-officially) dubbed their mission “Eight Days or Bust”, their private nomenclature for Gemini V would end up as “Eight Days in a Garbage Can”. The two astronauts had been assigned to the mission in February 1965, with Cooper having already flown the United States’ longest manned spaceflight at that time and Conrad making his first flight. With only six months to prepare, the two men and their backups—fellow astronauts Neil Armstrong and Elliot See—typically put in punishing 16-hour working days, plus weekends, as they aimed for a 1 August liftoff.

“We realized they needed more time,” wrote Deke Slayton, then-head of Flight Crew Operations, in his memoir Deke, co-authored with space historian Michael Cassutt. After consulting with senior NASA managers, Slayton succeeded in securing a three-week delay of Gemini V’s launch to 19 August. In spite of the workload, Cooper and Conrad found time to think of names for their spacecraft.

One idea was “The Conestoga”, in honor of one of the broad-wheeled covered wagons used during the United States’ westwards push in the previous century. They even created a conestoga patch, emblazoned with the legend “Eight Days or Bust”. But this was vetoed by NASA brass, who felt that it implied a mission of less than eight days might be perceived as a failure. Conrad’s alternative idea of “Lady Bird” was also nixed as it happened to be the nickname of then-First Lady Claudia “Lady Bird” Johnson and might be perceived as a derogatory slur. Finally, Cooper persuaded a reluctant NASA Administrator James Webb to approve the conestoga patch.

Preparations for Gemini V had already seen Conrad gain, then lose, the chance to make a spacewalk. In early plans for the mission, the Gemini IV pilot would depressurize the spacecraft’s cabin, open the hatch and stand on his seat, with an actual “egress”—a true Extravehicular Activity (EVA)—slated for Gemini V. But following the surprise spacewalk by Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov in March 1965, the U.S. spacewalk was correspondingly moved forward to Gemini IV. As a result, devoid of any EVA, Cooper and Conrad’s mission came to be grimly known by the two men as “Eight Days in a Garbage Can”, for they would be required to simply “exist” for a week in orbit and demonstrate that they could at least survive long enough for a minimum-duration round trip to the Moon.

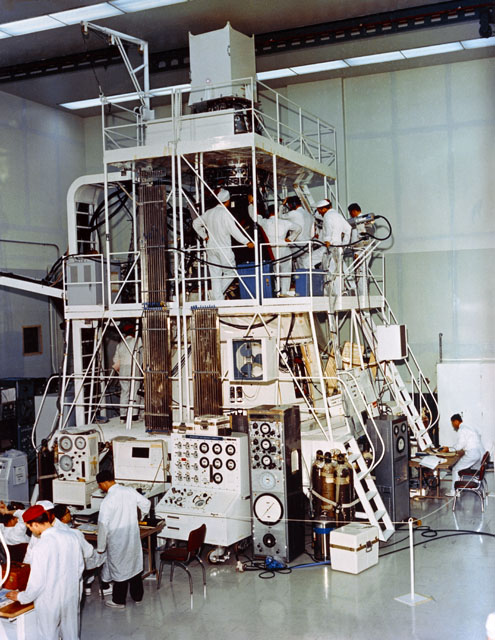

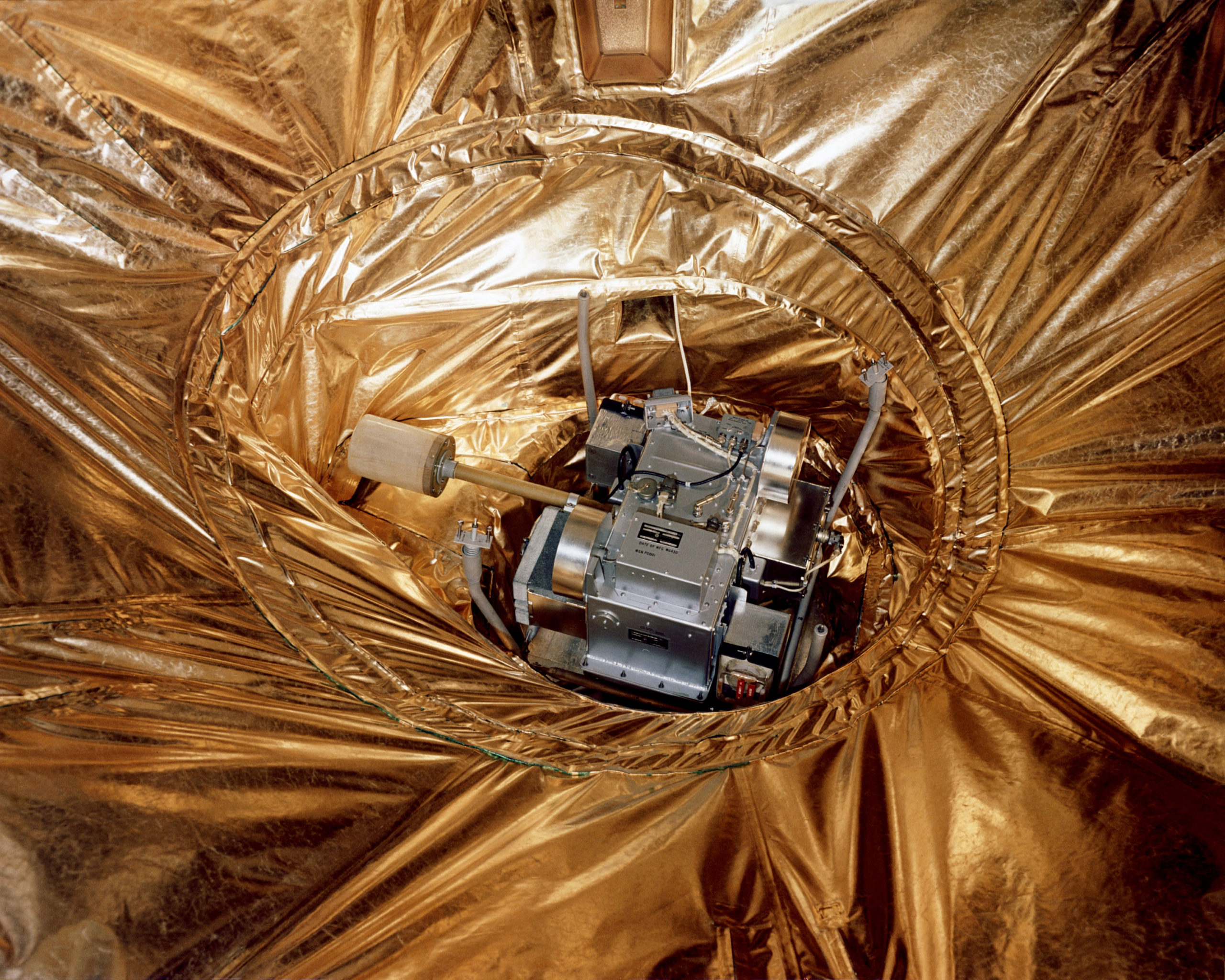

Yet Gemini V was far from dull. It would be the first Gemini to run on fuel cells, carried the first production rendezvous radar and was intended to include exercises with a Rendezvous Evaluation Pod (REP). Plans for it to utilize long-life thrusters were completed ahead of schedule and ended up flying on Gemini IV.

Unfortunately, 19 August would not be Gemini V’s day. Thunderstorms approached Cape Kennedy, rainfall fell in copious quantities and a lightning strike caused the spacecraft’s IBM-provided computer to quiver. The launch was scrubbed with only ten minutes remaining on the countdown clock and a disappointed Cooper and Conrad were extracted from the vehicle to try another day. They clambered back aboard on the 21st and no such problems manifested themselves. In the final minutes, Cooper turned to Conrad.

“You ready, rookie?”

Conrad shot him a pale-faced, nervous look. For a moment, Cooper looked concerned. Surely this decorated Navy fighter and test pilot wasn’t scared? Conrad milked the anxious silence for a few moments, then broke out into his trademark gap-toothed grin.

“Gotcha!” he guffawed. “Light this son-of-a-bitch and let’s go for a ride.”

And ride they did. One second before 9 a.m. EDT, the twin engines of their Titan II rocket ignited with a familiar, high-pitched whine and Gemini V was airborne.

However, it was not a smooth ascent to orbit. Cooper and Conrad found themselves buffeted by the effects of “pogo”—longitudinal oscillations which “bounced” the booster as it climbed ever higher through the rarefied atmosphere—which were particularly severe for 13 seconds or so. Eventually, by the time they got onto the Titan’s second stage, the effects lessened and were minimal for the rest of the climb. Conrad became the United States’ tenth man in space and, after Gemini V circled the globe once, Cooper became the first human to log two missions into Earth orbit.

In her book Rocketman, Nancy Conrad wrote that her husband compared the instant of liftoff to “a bomb going off under him” and described the Titan II’s fast climb away from Pad 14 as “a shake, rattle and roll, like a ’55 Buick blasting down a bumpy gravel road, louder than hell”. Within their first hours in orbit, the astronauts set to work releasing the REP for their rendezvous tests, but this work was soon overshadowed by a marked drop in pressure in the fuel cells. An oxygen supply heater element had failed and as pressures declined precipitously, there remained insufficient power to run the radar, radio and computer and Flight Director Chris Kraft told the crew to abandon the REP tasks.

At first, it did not seem outside the realm of possibility that Gemini V would indeed turn into an aborted missions; that its “eight days” really would turn out “bust”. Kraft ordered four Air Force aircraft to move into the recovery zone in the Pacific Ocean for a possible splashdown some 500 miles (800 km) northeast of Hawaii. A Navy destroyer and an oiler in the region were also placed on standby. In the meantime, Kraft told Cooper to shut down as many systems as possible and all efforts to resolve the fuel cell problem—even maneuvering Gemini V into direct sunlight to somehow stir the system back to life—were in vain. After three orbits, and still only a few hours into their mission, the situation was miserable: much of the spacecraft was shut down as a re-entry on the sixth pass became increasingly likely.

Then, all at once, telemetry indicated that the fuel cell pressures had begun to stabilize. In Kraft’s words, “the rate of decrease is decreasing”. His comment was premature, for within minutes they dropped again, but eventually pressures leveled-out and Cooper expressed his opinion to press on for another day under the existing conditions. “We might as well try it,” he told Capcom Jim McDivitt at one point. After all, Gemini V’s cabin pressure held steady, as did the astronauts’ suits, and left unsaid was the lost pride of bringing this “busted” mission back home early. Kraft determined that Cooper and Conrad could remain in orbit for a “drifting flight” to reach the prime recovery zone in the Atlantic Ocean at some stage after their 18th circuit of Earth.

Power levels remained low and although few experiments could be performed, Kraft grew happier with the prognosis for a lengthier mission. By 22 August, a day after launch, the situation had begun to stabilize and pressures started to climb again. Gemini V was by no means out of the woods, however, and would continue to battle power issues throughout its flight. And with little else to do—“No new sea-stories to tell,” Conrad quipped, years later—they also had to battle insidious boredom. When they surpassed Soviet cosmonaut Valeri Bykovsky’s then-record duration of five days in space, the response from Cooper was a nonchalant “At last, huh?”

Returning to Earth on 29 August, just shy of eight full days, their week in a garbage can had indeed been a long, uncomfortable endurance slog. Cooper and Conrad had eclipsed a raft of human spaceflight duration records which, until Gemini V, were held exclusively by the Soviet Union. And they had proved that humans could survive the minimum amount of time needed to get to the Moon and back. For Conrad, that was just as well, for he wound up commanding Apollo 12 later in his career which saw him become the third man to set foot on the lunar surface.

But perhaps the greatest irony from Gemini V surrounds Conrad himself. Irreverant to the last, he missed out on being selected for the Project Mercury astronaut selection and was branded by the psychologists as unfit for long-duration spaceflight. On two of his four space missions, he went on to set new records for the United States…for long-duration spaceflight.

Remember this flight. Seems that the problems were not as well publicized back then.