As the midnight bell tolled out 2020, for the first time in its history, the International Space Station (ISS) hosted as many as seven people at the dawn of a new year. Two Russians, four Americans and a single Japanese astronaut currently form Expedition 64—the 64th long-duration resident crew to occupy the sprawling, multi-national outpost since the arrival of Bill Shepherd, Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko way back in November 2000—and the next dozen months promises to be nothing if not dramatic.

According to NASA, the Expedition 64 team of Russian cosmonauts Sergei Ryzhikov and Sergei Kud-Sverchkov, NASA astronauts Kate Rubins, Mike Hopkins, Victor Glover and Shannon Walker and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) veteran Soichi Noguchi took New Year’s Day off duty, ahead of a busy January which will see two cargo ship departures and possibly two sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) from the U.S. Operational Segment (USOS).

Next Tuesday, Northrop Grumman Corp.’s NG-14 Cygnus resupply craft—which arrived last October and is named in honor of fallen STS-107 hero Kalpana “K.C.” Chawla—will be robotically grappled by the station’s 57.7-foot-long (17.6-meter) Canadarm2 robotic arm and detached from its berth on the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Unity node. Following its departure, Cygnus will remain in autonomous free flight for about a month, supporting a range of experiments which include Northrop Grumman’s SharkSat technology demonstrator and the fifth outing of the long-running Spacecraft Fire Experiment (SAFFIRE-V).

Current plans are for a minimum of eight days of SAFFIRE-V activities, although in the case of last year’s SAFFIRE-IV runs aboard the NG-13 Cygnus this was possible for a somewhat longer period. “The tests are similar to those conducted on SAFFIRE-IV, but with either different materials or different ambient conditions,” NASA SAFFIRE Project Manager Gary Ruff explained in comments provided to AmericaSpace. “We were not able to run conditions at reduced pressure and elevated oxygen concentrations on SAFFIRE-IV, but plan to on SAFFIRE-V. We want to conduct tests at 8.2 psia and 34 percent oxygen by volume, which are the ambient conditions being considered for lunar landing systems. This will be one of the new things we plan to investigate on this flight.”

The NG-14 Cygnus is presently expected to perform a destructive re-entry in late January. Three weeks later, another Cygnus—NG-15, whose name has yet to be revealed—is slated to launch atop Northrop Grumman’s Antares 230+ booster from Pad 0A at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) on Wallops Island, Va., no sooner than 20 February. It will berth at the Unity nadir interface a couple of days later and is expected to remain at the ISS until late April.

Five days after the NG-14 departure, the first of SpaceX’s upgraded Cargo Dragons—which launched and arrived at the ISS just last month—will also undock from International Docking Adapter (IDA)-3 on the space-facing (or “zenith”) port of the Harmony node. In doing so, it will become the first U.S. uncrewed commercial vehicle to both dock and undock at the station.

Designated “CRS-21”, it is the 21st cargo-carrying Dragon to successfully reach and restock the ISS since 2012 and the first mission under the second-phase Commercial Resupply Services (CRS2) contract, signed between SpaceX and NASA back in early 2016. Unlike Cygnus, Dragon is capable of returning cargo back to Earth and is expected to ferry about 5,200 pounds (2,360 kg) of payloads and experiment results back to a parachute-assisted splashdown and into the eager hands of researchers.

Up to three sessions of EVA are tentatively scheduled for the early part of the year, although exactly which members of the USOS crew will participate has yet to be announced. Certainly, all but Walker and Glover have performed spacewalks in their earlier careers, with Rubins and Hopkins having each made two EVAs and Noguchi three. The first spacewalk is expected to complete the installation of the Bartolomeo payloads-anchoring platform and the Columbus Ka-Band Antenna (COL-Ka) onto Europe’s Columbus lab, with the second will tend to the removal and replacement of the final battery on the station’s S-6 truss and a third dedicated to maintenance tasks.

A period of spacecraft “musical chairs” is expected in March, as the ISS prepares for the arrival of the next Russian crew-carrying Soyuz and the next USOS crew-carrying Dragon. Ryzhikov, Kud-Sverchkov and Rubins will board the Soyuz MS-17 vehicle which they flew to the station last October, undock from the nadir-facing Rassvet module of the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and redock at the zenith-facing Poisk module. This will open up Rassvet for the arrival of Soyuz MS-18 and its three-person relief crew in the second week of April.

And at the end of March, Hopkins, Glover, Walker and Noguchi will board Dragon Resilience—the ship which ferried them to the ISS in mid-November—and undock from the IDA-2 port at the forward end of Harmony. They will redock at the zenith-facing IDA-3 port to make room for the arrival of Boeing’s second uncrewed test flight of its CST-100 Starliner, which is currently targeted to launch no earlier than 29 March.

The CST-100 Starliner, which endured a troubled maiden test flight in December 2019, will spend about four days docked to the ISS, before departing on 3 April and returning to Earth. Successful completion of this milestone will allow Boeing to press ahead with its second critical certification task: a two-week crewed test flight no earlier than June, carrying NASA astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore, Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann.

By the time Wilmore & Co. arrive, the station’s crew will have changed yet again. Ryzhikov, Kud-Sverchkov and Rubins are slated to depart aboard Soyuz MS-17 in mid-April and return home, wrapping up 185 days in space. Less clear is the targeted launch date of Dragon Endeavour and Crew-2 astronauts Shane Kimbrough, Megan McArthur, Japan’s Aki Hoshide and France’s Thomas Pesquet to replace the outgoing Crew-1 Dragon Resilience team of Hopkins, Glover, Walker and Noguchi.

Launch of Crew-2 was reportedly targeted for no sooner than 30 March, although with CST-100 Starliner docked operations and a Soyuz crew changeover also planned in this tightly-packed timeframe, it seems likely that Kimbrough, McArthur, Hoshide and Pesquet will launch later in April. This will produce a return to Earth for Hopkins’ crew in the early part of May after an approximately six-month stay on the ISS.

In any case, Crew-2 will arrive after the departure of the CST-100 Starliner, in order to take up residence at the IDA-2 forward port. And following the departure of Dragon Resilience and the Crew-1 astronauts from IDA-3, Kimbrough’s team will relocate their Dragon Endeavour to IDA-3, ahead of the arrival of the CRS-22 Dragon cargo ship in the second week of May.

With the departure of Ryzhikov, Kud-Sverchkov and Rubins, Expedition 65 will formally commence, likely under the command of Russian cosmonaut Oleg Novitsky, who is expected to lead Soyuz MS-18. His crew may comprise fellow Russians Petr Dubrov and Sergei Korsakov, although it remains to be seen if a seat on the Soyuz will instead go to a U.S. astronaut as part of a “barter” deal for a cosmonaut seat on the Crew-3 Dragon mission in the fall.

Indeed, Crew-3—led by the first “rookie” astronaut to command a U.S. crewed vehicle in four decades—is presently only 75-percent complete, with NASA astronauts Raja Chari and Tom Marshburn joined by Germany’s Matthias Maurer. A fourth, as-yet-unfilled seat aboard the Crew Dragon may go to a Russian cosmonaut or perhaps another USOS crew member.

From mid-year onwards, the plate of missions remains more uncertain, with the CRS-22 Dragon cargo ship expected to depart in June and two others—CRS-23 and CRS-24—provisionally booked for August and November. As previously outlined by SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell, this is expected to see at least one Dragon, whether crew or cargo, aboard the ISS throughout 2021. Much of the summer is expected to focus on the ROS, with the long-awaited Nauka (“Science”) lab due to arrive in July and a series of EVAs to connect cables and complete the installation and activation of the European Robotic Arm (ERA) onto the new module.

Crewing for missions later in 2021 also remains somewhat uncertain. With the announcement by Houston-based AxiomSpace to fly an all-commercial Crew Dragon late in the year, reportedly carrying former shuttle spacewalker and ISS commander Mike Lopez-Alegria and joined by film director Doug Liman, Israeli fighter pilot and businessman Eytan Stibbe and none other than movie star Tom Cruise, rumor has persisted that the Russians intend to launch at least one film star for a short-duration Soyuz flight in October.

This would presumably require at least one member of the Soyuz MS-18 crew to remain aboard the ISS for almost a full year, in order to open up one (or two) return seats for the Russian film stars. At present, however, little has been announced in the way of certainty.

But what is not in doubt is that 2021 will be a unique and dramatic for the space program, as Commercial Crew enters its stride with regular Crew Dragon flights—and “direct-handover” operations which should see an uninterrupted presence of at least a crew of seven at all times—and the long-awaited certification of the CST-100 Starliner. Three Cargo Dragons and a Cygnus, together several Russian Progress cargo ships, the arrival of Nauka and multiple USOS and ROS spacewalks, will make the ISS a busy place.

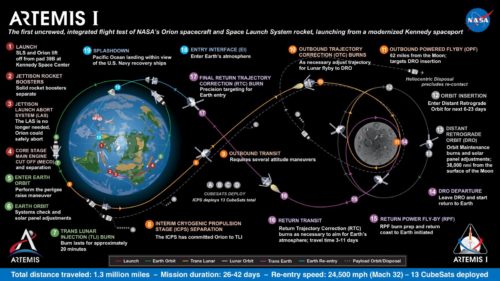

And although uncrewed, the scheduled maiden launch of NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) super-heavylift rocket, presently targeted for no sooner than November on its Artemis-1 circumlunar voyage, offers a tantalizing glimpse at the future as America and its partners seek to plant boots on the Moon by 2024.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » SLS » Artemis »

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:NASA, AxiomSpace Leaders Discuss Historic Ax-1 Space Station Mission « AmericaSpace

Pingback:NASA, AxiomSpace Leaders Discuss Historic Ax-1 Space Station Mission