As SpaceX prepares to launch its second operational rotation mission to the International Space Station (ISS) next month, fellow Commercial Crew Program partner Boeing has met with additional delay as its CST-100 Starliner aims for a second uncrewed Orbital Flight Test (OFT-2).

Originally scheduled to launch on 25 March, then postponed to no earlier than 2 April, the week-long mission now looks set to be pushed back yet further in response to a full plate of Visiting Vehicle (VV) traffic at the sprawling multi-national orbital outpost. “Based on the current traffic at the space station, NASA does not anticipate that OFT-2 can be accomplished later in April,” the space agency reported Thursday.

It is yet another bitter blow for Boeing’s troubled spacecraft, which first launched atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V booster for its long-awaited OFT-1 mission to the ISS at 6:36 a.m. EST on 20 December 2019. However, shortly after attaining orbit, an automated timing issue aboard Starliner forced flight controllers to call off its rendezvous and docking with the ISS and the mission returned safely to Earth two days later, becoming the first U.S. human-rated capsule to touch down on solid ground when it landed via a combination of parachutes and air bags at White Sands, N.M., early on 22 December.

Despite the disappointment of an incomplete OFT-1 mission, Starliner successfully demonstrated its propulsion systems, its communications systems, its Guidance, Navigation and Control (GNC), its Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS) and—through a series of in-flight extension/retraction tests—its NASA Docking System (NDS).

Although NASA later noted that an actual ISS docking was not a mandatory requirement to “crew-certify” Starliner, and pointed out that had astronauts been physically aboard OFT-1 they could have taken manual control and likely overcome the automated timing problem, it became increasingly likely as 2020 dawned that a reflight would take place.

A High Visibility Close Call (HVCC) Review, led by NASA Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations Kathy Lueders and Commercial Crew Program Manager Steve Stich revealed a worrisome number of technical and organizational root causes for the difficult mission. In March 2020, an joint NASA/Boeing Independent Review Team (IRT) found that three principal anomalies had plagued the flight. Two were classified as “software coding errors”.

Specifically, Starliner incorrectly synched its Mission Elapsed Timer (MET) with the Atlas V before the onset of the Terminal Countdown, leading it to presume that it was at a different point in its mission following separation from the booster and correspondingly failing to perform its correct maneuvers at the proper time. And another issue might have impaired the successful separation and disposal of its service module at the mission’s end.

“Ground intervention”, it became clear, had prevented a Loss of Vehicle incident in both of these software anomaly events. A third issue revolved around an unanticipated loss of Space-to-Ground Communications, where an intermittent forward-link issue impeded flight controllers’ efforts to command and control the spacecraft. This was traced to Radio Frequency (RF) interference with Starliner’s communications system. Had astronauts been aboard OFT-1, the ability of Mission Control to establish reliable voice communications with the crew might have been adversely impacted.

In its overview, NASA outlined 80 recommendations to be addressed with Boeing after the conclusion of the HVCC process. Areas of focus fell into five broad categories. Twenty-one related to testing and simulation, emphasizing the need for greater hardware and software integration testing, performance of an end-to-end “run-for-record” test before each flight, reviews of subsystem behaviors and limitations and the identification of simulation and emulation gaps.

Ten pertained to assessment of all software requirements with multiple logic conditions to ensure full test coverage. Thirty-five others required modifications to Change Board documentation, bolstering the numbers of participants in peer reviews and test data reviews and and “increasing the involvement of subject matter experts in safety-critical areas”. Seven dealt with the need for changes to the NASA/Boeing safety culture, whilst another seven focused upon updates of the Starliner software coding issues which caused the MET and service module separation problems.

Following the investigation, Boeing committed to review and correct the software coding for the MET and service module disposal burns, strengthened its review processes and enhanced the fidelity of its testing to ensure overall “product integrity”. Early in April 2020, the company announced plans to fly an uncrewed OFT-2 mission, at no added cost to the U.S. Government, although that mission—originally targeted for last fall—has met with significant delay, which pushed it firstly into early January 2021, then late March, then early April and now later in the spring or even early in the summer.

In the meantime, testing of the spacecraft systems continued unabated, with additional parachute trials at White Sands during the second half of 2020 under “dynamic abort conditions and a simulated failure”. And in January, Boeing reported that it had formally requalified Starliner’s flight software load, ahead of OFT-2.

That work involved an intricate series of static and dynamic tests in the Avionics and Software Integration Lab (ASIL) in Houston, Texas, which validated software performance in tandem with the recommended flight hardware across “hundreds of cases, ranging from single-command verifications and comprehensive end-to-end mission scenarios with the core software”. Originally targeting a 29 March launch, this date was initially moved forward to the 25th, then back to no sooner than 2 April.

This additional delay was caused by a need for additional time for hardware processing. Avionics units aboard the spacecraft required replacement following a power surge due to a Ground Support Equipment (GSE) configuration issue during final checkouts last month. But with a packed Visiting Vehicle coming-and-going manifest for much of April and into May, it now looks likely that the OFT-2 flight will be delayed yet further.

“Boeing and NASA have worked extremely hard to support an early-April launch but we need to assess alternatives to ensure NASA’s safety work can be accomplished. NASA and Boeing know we fly together,” said Kathy Lueders. “Boeing has done an incredible amount of work on Starliner to be ready for flight and we’ll provide an update soon on when we expect to launch the OFT-2 mission.”

“I’m grateful for the extraordinary work being undertaken by our NASA partners as we progress towards our OFT-2 mission,” added John Vollmer, vice president and program manager of Boeing’s Commercial Crew Program. “And I’m very proud of the Boeing Starliner team for working so diligently to get the hardware, software and certification closure products ready for flight. We’re committed to demonstrating the safety and quality of our spacecraft and progressing to our crewed test flight and the missions beyond.”

Current plans call for Soyuz MS-18 to launch a new crew from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on 9 April, after which Soyuz MS-17 crew members Sergei Ryzhikov, Sergei Kud-Sverchkov and Kate Rubins are due to return to Earth around the 17th. After that, Crew-2 astronauts Shane Kimbrough, Megan McArthur, Aki Hoshide and Thomas Pesquet are slated to ride SpaceX’s Dragon Endeavour uphill on the 20th and dock at the space station the next day.

And Crew-1 astronauts Mike Hopkins, Victor Glover, Shannon Walker and Soichi Noguchi will come home aboard Dragon Resilience in late April or early May. With a Russian Progress cargo ship also expected to depart the ISS at the end of April, it does not seem unreasonable to suppose that OFT-2 may now unavoidably slip into the May timeframe.

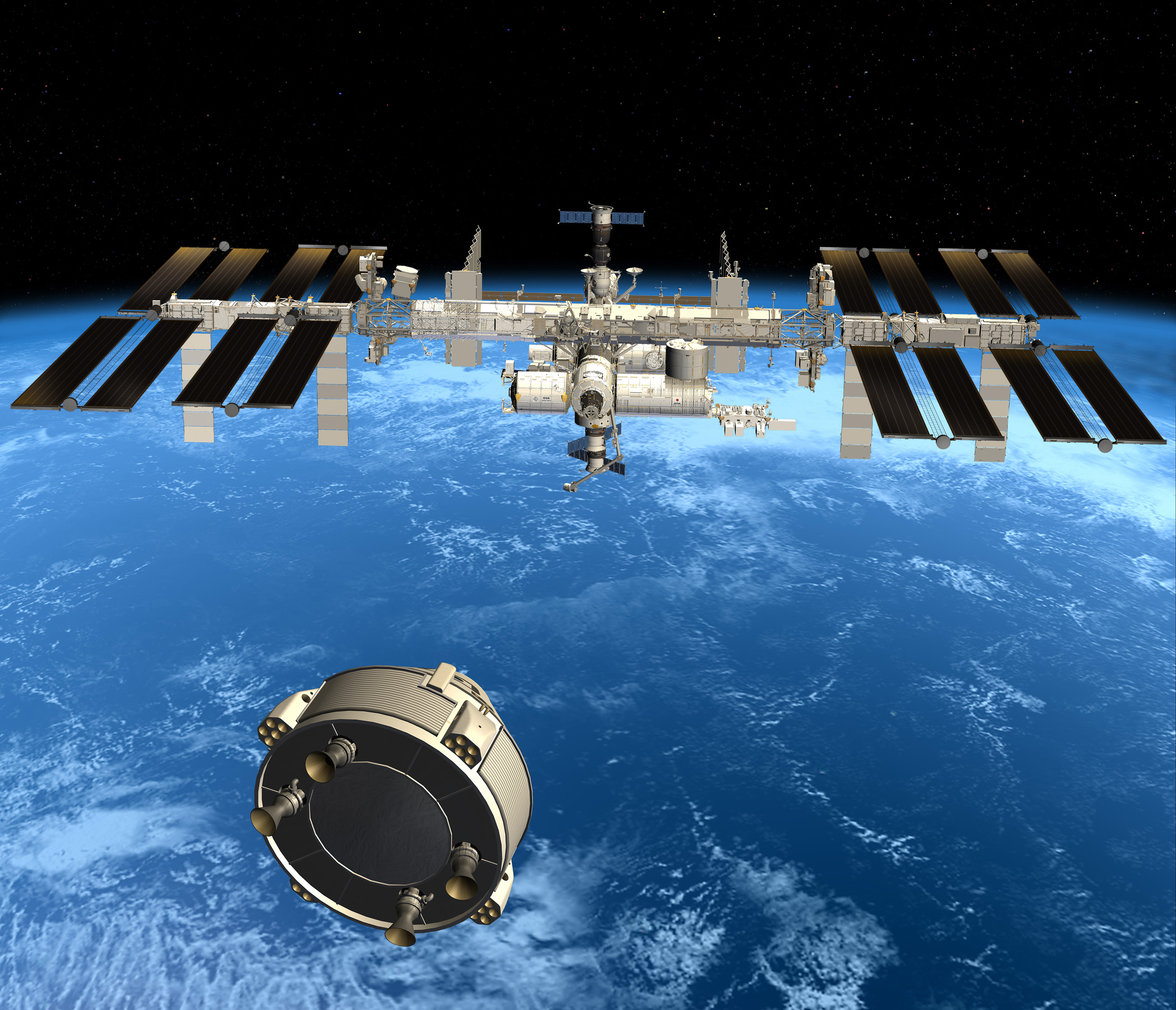

Looking ahead, OFT-2 is set to last approximately a week and will dock and undock autonomously at International Docking Adapter (IDA)-2, on the forward-facing port of the station’s Harmony node. Assuming that the mission runs without significant wrinkles, the Crew Flight Test (CFT)—comprising Commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore, Pilot Nicole Mann and Joint Operations Commander (JOC) Mike Fincke—is targeted to launch no earlier than September.

An exact duration for CFT remains to be confirmed, with initial expectations of a flight lasting about two weeks, although in April 2019 NASA and Boeing indicated an intention to fly a longer mission. But with direct handovers planned between the SpaceX Crew-2 and Crew-3 Dragons later this year, and similar direct handovers between the Soyuz MS-18 and MS-19 missions in the fall, the ISS already has a fully-booked staff of seven throughout 2021, raising the prospect that CFT may revert to a shorter-duration flight.