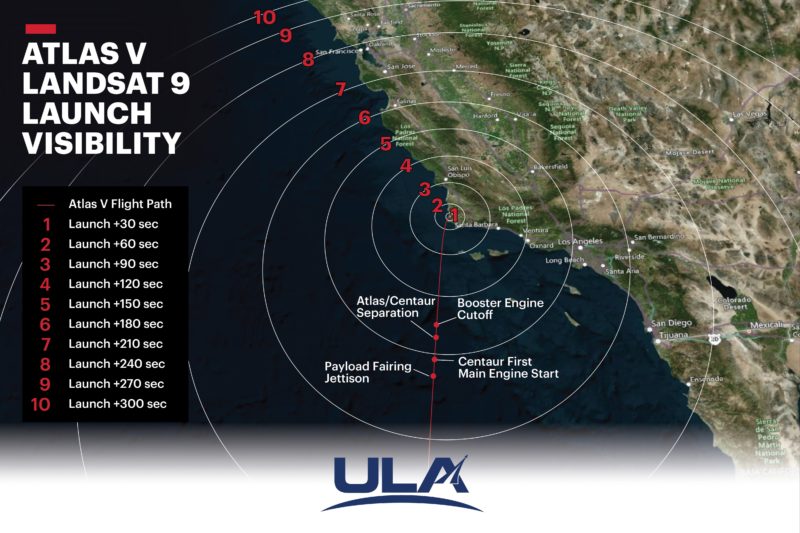

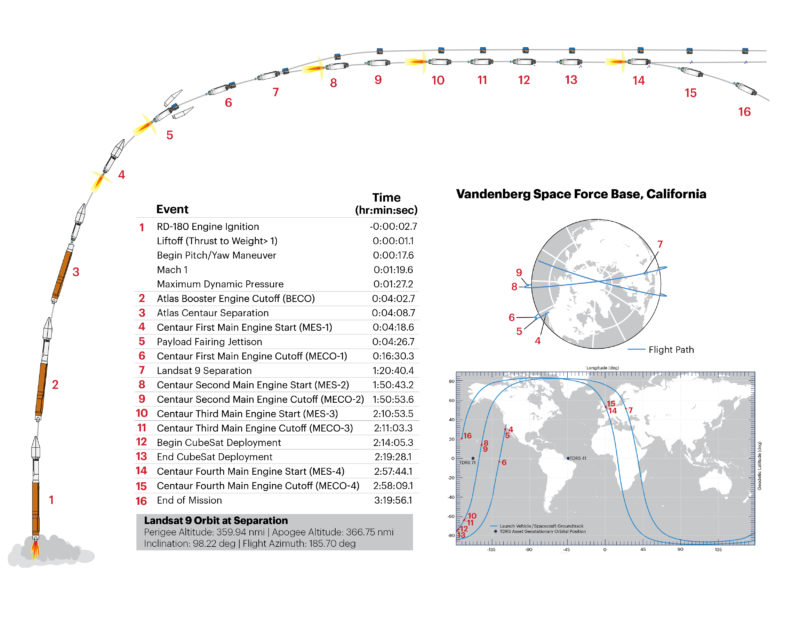

After what has so far been its least-flown year on record, United Launch Alliance (ULA) stands primed to fly a second “Mighty Atlas” of 2021 from Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif., on Monday afternoon. The “barebones” Atlas V 401 rocket—characterized by a 13-foot-diameter (4-meter) payload fairing, no solid-fueled strap-on boosters and a single-engine Centaur upper stage—is set to rise from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-3E at the West Coast launch site at 11:12 a.m. PDT, at the start of a 30-minute “window”. Primary payload is Landsat-9, flying on behalf of NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Tomorrow’s flight also marks the 300th member of the Atlas missile family to originate from Vandenberg since September 1959, marking over six decades of active operational service.

It has been a troubled year for ULA and several of its payload customers, as original plans to fly two Delta IV Heavy missions out of Vandenberg, multiple Atlas V launches in support of U.S. Government, scientific and commercial programs and the maiden voyage of the new Vulcan-Centaur heavylifter to send Astrobotic Technology’s Peregrine lunar lander to the surface of the Moon met with significant delay.

The problems began early, when an Atlas V dedicated to the Space Test Program (STP)-3 mission—originally targeted to fly in late February—was postponed due to concerns about the readiness of its STPSat-6 primary payload. Initially pushed to late June, it succumbed to further delay when an Atlas V launch in mid-May experienced anomalous behavior in the performance of its Centaur’s RL-10C engine.

Added to these woes, the second Orbital Flight Test (OFT-2) of Boeing’s troubled CST-100 Starliner spacecraft to the International Space Station (ISS) slipped from March to July, before being stood down indefinitely last month due to unexpected valve-position indications in its propulsion system.

As a consequence, ULA has thus far accomplished only two launches of an anticipated ten-launch 2021 manifest. On 26 April, a triple-barreled Delta IV Heavy thundered aloft from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-6 at Vandenberg, carrying the highly secretive NROL-82 payload for the National Reconnaissance Office. And three weeks later on 17 May, an Atlas V rose from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., laden with the fifth geostationary-orbiting element of the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS GEO-5).

But hopes to fly STP-3 on 23 June and OFT-2 six weeks later ultimately came to nought, leaving Landsat-9—originally baselined to fly No Earlier Than (NET) 16 September—as ULA’s third launch of the year.

Despite its numerical designator, Landsat-9 is actually the eighth satellite to achieve orbit in a lengthy collaborative effort between NASA and the USGS and is tasked with providing moderate-resolution observations of Earth’s terrestrial and polar regions at visible and infrared wavelengths.

Like its ancestors, Landsat-9 will support future land planning and water-use monitoring, as well as serving as a first-responder to natural disasters and an ever-present watchman over our planet’s ever-changing climate, ecosystems, water cycle, surface and interior. And like its immediate predecessor, Landsat-8—originally known as the Landsat Data Continuity Mission (LDCM) and launched in February 2013—the new spacecraft will ride ULA’s workhorse Atlas V booster.

Conceived back in the 1960s as the Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS), one of the Landsat program’s principal instruments—its multispectral scanner—was completed and tested a few months after Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon.

The first mission in the series roared into near-polar orbit from Vandenberg in July 1972 and three years later the program was renamed “Landsat”. Solar overheating caused it to be shut down in early 1978, but Landsat-1 opened the door to a remarkable future.

Landsats-2 and 3 went on to endure well beyond their targeted one-year operational life spans, but Landsat-4 in mid-1982 brought disappointment. Shortly after launch, it lost half of its electrical power, as well as its ability to transmit scientific data.

To compensate for the loss, a backup spacecraft, Landsat-5, was launched in early 1984. At one stage, plans were advanced to launch a shuttle mission from Vandenberg in 1987 to repair and refuel Landsat-4, but this was shelved in the aftermath of the Challenger tragedy.

However, with the arrival of NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS), Landsat-4 rallied and even aided Landsat-5 for a period in 1987 when the latter experienced problems of its own. Landsat-4 marked the first use of the Thematic Mapper, which gathered data across seven spectral bands and achieved far greater resolution than its predecessors. Not until 1993 did Landsat-4 eventually retire from service.

And as for Landsat-5, this hardy satellite remained operational until 2013, despite difficulties suffered in its old age with its backup solar array drive mechanism, its power and attitude-control systems and fluctuations in its critical data-transmission amplifier.

Landsat-6 failed to reach orbit in 1993, but Landsat-7 met with greater success in 1999. A malfunction in its Enhanced Thematic Mapper marred an otherwise highly successful mission, which continues to function to this day, with hopes that Landsat-7 may be visited and refueled by NASA’s Maxar-built Restore-L vehicle in 2025. More recently, Landsat-8 arrived in February 2013 and remains operational, notwithstanding anomalous electrical current levels associated with its Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS).

As it approaches the dawn of its sixth decade of service, Landsat’s contributions have been truly remarkable. It even helped discover an island, 12 miles (20 km) off the northeastern coast of Labrador, which was later named in its honor. The 12,000-square-foot (1,125-square-meter) “Landsat Island” was found in 1976, during a Canadian survey which utilized Landsat-1 data to find hitherto-uncharted landmarks.

Lowered by a helicopter harness, Dr. Frank Hall of the Canadian Hydrographic Service narrowly missed being swiped by a polar bear and almost became the first person to meet his maker on Landsat Island.

Initiation of the Landsat-9 program began in early 2015, with expectations that the mission would carry similar instrumentation to Landsat-8: the Operational Land Imager (OLI-2), built by Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp., of Broomfield, Colo., which is sensitive to the visible, near-infrared and shortwave-infrared portions of the electromagnetic spectrum, and the Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS-2), supplied by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) of Greenbelt, Md.

The latter will examine land-surface temperatures across two thermal infrared bands. Together, OLI-2 and TIRS-2 will cover wide geographical areas, whilst also providing adequate imagery of urban centers, farms and forests.

At the point of conception, Landsat-9 was scheduled to launch in December 2020. Contracts worth $129.9 million to build the satellite were awarded to Orbital ATK—later purchased by Northrop Grumman Corp.—in October 2016 and the program passed smoothly through its System Requirements Review (SRR) and Preliminary Design Review (PDR) the following year. In October 2017, ULA won the contract to launch Landsat-9. Under the terms of the contract, launch was targeted for June 2021, “while protecting for the ability to launch as early as December 2020”.

“We are proud to continue to serve as the primary launch provider for Landsat missions,” said Gary Wentz, ULA’s vice president for government and commercial programs. “The Landsat series provides outstanding data for Earth environment and science-based research and Landsat 9 will add to these capabilities. We have worked alongside our partners, in a challenging health environment, to prepare to launch this important mission that will empower Earth research from space for decades to come.”

Over the next few years following the contract awards, the Landsat-9 hardware gradually came together. The flight cryocooler for TIRS-2 was delivered ahead of schedule in 2018 and the program passed through a virtually wrinkle-free Critical Design Review (CDR). In January 2020, OLI-2 and TIRS-2 were successfully integrated aboard Landsat 9, although the worldwide march of the COVD-19 coronavirus pandemic pushed the launch date inexorably to the right: firstly to NET June 2021 and ultimately September.

By the spring of this year, Landsat-9 had wrapped up thermal-vacuum testing at Northrop Grumman’s facility in Gilbert, Ariz., after which teams pressed directly into electrical testing, spacecraft closeouts and a final Pre-Ship Review and Flight Operations Review/Operations Readiness Review in late June. The 5,900-pound (2,700 kg) satellite arrived at Vandenberg on 8 July to commence pre-launch processing. Last month, it passed its final major lifecycle approval gateway—Key Decision Point-E (KDP-E)—which furnished formal approval to proceed to launch and early orbital operations.

In the meantime, the Centaur upper stage and bullet-like Extra-Extended Payload Fairing (XEPF)—the latter of which will house Landsat-9 for its climb to space—were delivered to Vandenberg, followed by the 107-foot-tall (32-meter) Atlas V Common Core Booster (CCB).

On 13 July, in the foggy gloom of a Vandenberg morning, the CCB was raised vertically by the overhead Mobile Service Tower (MST) crane and placed onto the Fixed Launch Platform (FLP). Two days later, the Centaur was affixed atop the CCB, followed by the lower segment of the payload fairing on the 17th.

Elsewhere, in mid-August, Landsat-9 was mated to its payload adapter and encapsulated inside the XEPF, which stands 13.7 feet (4 meters) tall. As the month headed towards its end, however, more delays were afoot, as the COVID-19 pandemic’s demands for medical liquid oxygen impacted the delivered of liquid nitrogen to Vandenberg. Since gaseous nitrogen is a necessary element of the pre-launch vehicle testing and countdown sequences, launch was correspondingly moved to NET 23 September.

More recently, ULA teams completed a fully-fueled Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR) of almost the entire countdown on SLC-3E. Such rehearsals are typically conducted prior to national security launches or missions with critically narrow “launch windows” and serve to evaluate vehicle and ground systems in order to mitigate any issues ahead of Launch Day.

The Atlas V had been loaded with a highly refined form of rocket-grade kerosene, known as “RP-1”, on 20 August. And on 3 September, led by ULA Launch Conductor Scott Barney at Vandenberg’s Remote Launch Control Center, the WDR got underway. During the multi-hour process, the 26-story MST was retracted and the Atlas V and Centaur were loaded with 66,000 gallons (300,000 liters) of liquid oxygen and hydrogen.

Veteran ULA Launch Director Tom Heter III oversaw that fueling operation and for him tomorrow’s launch of Landsat-9 promises to be particularly poignant. His father, veteran Lockheed Martin head of Vandenberg operations Tom Heter II, who died in 2019, will be honored with a commemorative decal on the side of Mighty Atlas. Recently, the Heter family toured SLC-3E and witnessed the decal being added to the rocket.

“Tom was a devoted family man, a great leader, a true patriot and a highly respected member of the aerospace industry,” reads the mission dedication. “He was also dedicated to serve in the local communities by providing volunteer and charitable support. Through his hard work and dedication, Tom helped shape and lay the groundwork for the space lift operations as we know them today.”

During the WDR, clocks counted down to the final seconds, before the cutoff call was issued. The rocket was safed, the cryogens were drained and the MST was returned to surround the vehicle for final operations.

But as September wore on, out-of-tolerance high winds and conflicts with other Western Range customers impacted the critical task of moving the XEPF from the Integrated Payload Facility (IPF) to SLC-3 for installation atop the Atlas V. The result was yet another launch postponement, with T-0 now pushed back from 23 September to the morning of the 27th.

Payload integration was finally completed three days later than planned on 15 September, raising the height of the stack to 194 feet (59.1 meters). The Launch Readiness Review (LRR) concluded yesterday, with T-0 refined slightly to 11:12 a.m. PDT.

Weather conditions for tomorrow’s opening launch attempt are 90-percent acceptable, with ground winds expected to reduce this favorable picture to 60 percent in the event of a 24-hour postponement to Tuesday.

“A weather system approaching from the northwest early next week will bring seasonal summertime conditions for Vandenberg on Monday,” noted ULA in a Friday morning weather update, “with a marine layer of low stratus clouds and fog.” The present forecast identifies complete overcast conditions of low-level clouds at 500 feet (150 meters), visibility of 3-5 miles (5-8 km) in fog and temperatures near 16 degrees Celsius (61 degrees Fahrenheit).

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

Missions » Landsat »

Why so many burns after separation?