Thirty years have now passed since the International Space Year (ISY) in 1992, when 29 national space agencies and ten international organizations participated in various activities to promote exploration of the cosmos and our home planet, Earth. And although a pair of Russian cosmonauts—Aleksandr Volkov and Sergei Krikalev—were aboard the Mir space station on New Year’s Day, the first crewed launch of 1992 was a major venture in life and microgravity research, involving 200 scientists from the space agencies of the United States, Germany, France, Canada and Japan.

But for the success that the first International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-1) enjoyed, STS-42 was shadowed by crew changes and an appalling human tragedy.

Before the catastrophic loss of shuttle Challenger in January 1986, the IML series was meant to feature three missions, utilizing Europe’s 23-foot-long (7-meter) Spacelab pressurized module in the orbiter’s payload bay. At the time of STS-51L, IML-1 was targeted for a May 1987 launch, but with the enforced grounding of the fleet it was rescheduled for December 1990.

The sensitive nature of its experiments required the shuttle to occupy a “pseudo-gravity-gradient” orbit, with its tail directed toward Earth, at a mean altitude of 160 miles (300 kilometers). But during the course of 1990, fleetwide hydrogen leaks caused STS-42 to slip repeatedly, firstly into 1991 and then into early 1992.

One of the consequences of these lengthy delays was that IML-1 moved from shuttle Columbia—the longest-serving member of NASA’s fleet—onto Atlantis and ultimately her sister, Discovery. “We moved from one orbiter to another orbiter,” remembered STS-42 Mission Specialist Bill Readdy in a NASA oral history.

“The silver lining for us, though, was originally, it was a due-east flight, 28.5-degree flight. As a result of going from Columbia, which was the queen of the fleet, the oldest and the heaviest, to Discovery, we were able to go to an inclined orbit of 57 degrees instead.”

This would furnish the-42 crew with views as far as 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) in all directions. “You’re seeing the upper part of Alaska, the Aleutian chain,” said Readdy. “South, you can kind of see the Antarctic. You’re going over New Zealand, Australia and well south into South Africa and Tierra del Fuego. From an Earth observation standpoint, it made the flight much, much more interesting. Of course, the down side was you’re supposed to spend most of your time in the laboratory, not looking out the window!”

To facilitate planning for a mission which was envisaged as an early demonstration of research on Space Station Freedom, members of the IML-1 science crew were named in advance of the orbiter crew and a new astronaut designator was conceived. In June 1989, veteran astronauts Norm Thagard and Mary Cleave were announced as Mission Specialists and a cadre of four international scientists—Canadians Ken Money and Roberta Bondar, Germany’s Ulf Merbold and Roger Crouch of the U.S.—were selected to train for a pair of Payload Specialist seats.

Within months, however, everything changed. In early January 1990, Commander Ron Grabe, Pilot Steve Oswald and Readdy were assigned as the orbiter crew. “They pushed this press release in front of us and said ‘You have any problem with that?” Readdy recalled. “I had to read it three or four times before I realized what it was. I saw Oswald’s name on there, but my name didn’t pop out.”

Readdy’s first reaction was to congratulate Oswald.

“Well, buddy,” replied Oswald, “you’re going, too!”

But that same month, Cleave resigned her place on the crew “for personal reasons” and was replaced by another astronaut, Manley “Sonny” Carter. Years later, Cleave rationalized that she had returned from her two previous shuttle missions, shocked by the rate at which Earth had succumbed to negative environmental change.

“Cities were gray smudges,” she said. “The air looked dirtier, less trees, more roads.” She opted to rotate out of the Astronaut Office to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Md., to work robotic environmental projects. A year later, she became deputy project manager for GSFCs’ Sea-Viewing Wide Field-of-View Sensor (SeaWIFS) mission.

At the same time that Cleave left STS-42, Thagard was named as the flight’s “Payload Commander”, a role which NASA “expected to serve as a foundation for the development of a Space Station Mission Commander concept”, as well as enabling “long-range leadership in the development and planning of payload crew science activities”.

One facet of Thagard’s payload leadership came with the change of orbiters from Columbia to Atlantis and eventually Discovery. At that time, Columbia was the only orbiter capable of housing five cryogenic reactant tanks under her payload bay floor for the electricity-generating fuel cells and as such only she could support the planned ten-day STS-42 flight. Atlantis and Discovery, on the other hand, accommodate four cryogenic tanks apiece, and could support a shorter mission length of around a week.

As the STS-42 crew continued to train, it therefore became evident that their mission content would remain the same, but their flight duration would be several days shorter. Then, on the afternoon of 5 April 1991, Atlantic Southeast Airlines Flight 2311 crashed near Glynco Jetport (today’s Brunswick Golden Isles Airport) in Brunswick, Ga., after an hour-long commercial flight from Atlanta. Approaching the runway at low altitude, the jet suddenly rolled sharply to the left and hit a patch of trees, nose-first. All 23 passengers and crew were killed. One of those passengers was STS-42’s Sonny Carter.

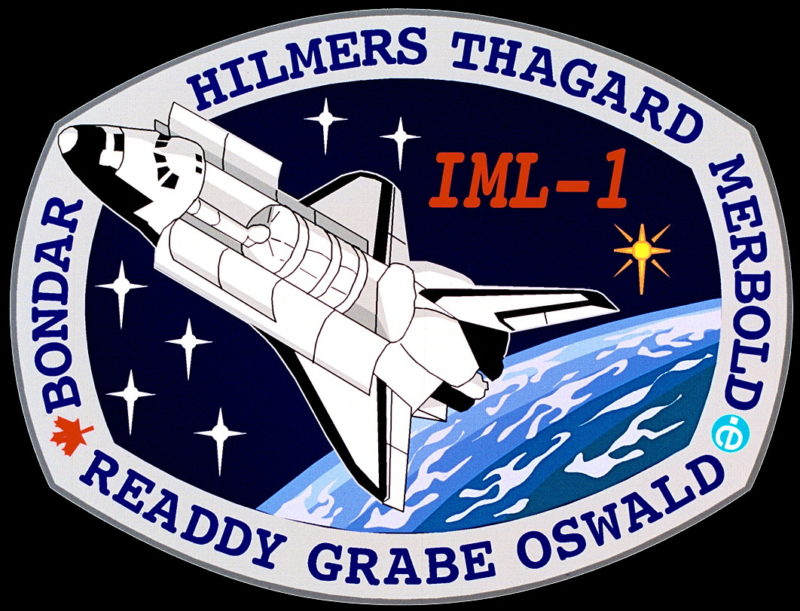

Two weeks later, as NASA reeled from the tragedy, astronaut Dave Hilmers was named to replace Carter. And when the STS-42 crew released their official patch later that year, it included a single gold star in memory of “our crewmate, colleague and friend”.

By the time of Hilmers’ assignment, launch was only nine months away. But Hilmers, a veteran astronaut, never missed a beat. “You couldn’t throw too much information at him,” said Readdy. “The guy’s just a sponge and able to absorb it all and then somehow figure out how to process it and spit it back at you.” IML-1 would be a dual-shift mission, with “red” and “blue” teams working the Spacelab experiments around-the-clock. Grabe, Oswald, Thagard and Roberta Bondar would be on the blue team, with Readdy, Hilmers and Merbold on the red team.

Finally, on the morning of 22 January 1992—three decades ago, today—the seven astronauts walked out of the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, bound for historic Pad 39A. Liftoff was targeted for 8:54 a.m. EST, at the opening of a 2.5-hour “window”, but a hydrogen pump motor issued forced a slight delay. At length, Discovery roared aloft at 9:52 a.m.

From his seat on the right side of the shuttle’s cockpit, Oswald found the first launch of his astronaut career somewhat hard to describe. “The vibration and raw power that’s being exerted on the vehicle during the first two minutes of the flight is truly awesome,” he said.

“The view that I was getting out the right side of the vehicle during ascent was truly spectacular, looking out on the East Coast.” When the twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) were jettisoned at two minutes into ascent, Oswald likened the effect to “an automobile accident”, as noise and light flooded into the cabin.

Over the next week, the STS-42 crew worked on dozens of experiments, devoted to materials and life sciences in the peculiar microgravity environment. At times, recalled Hilmers, traffic through the long tunnel which linked the shuttle’s middeck with the Spacelab module was so busy that they wished they had installed traffic lights.

And the crew’s lenient expenditure of consumables meant that the mission could be extended from seven to eight days, with Discovery touching down smoothly at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., at 8:07 a.m. PST on 30 January.

But for the huge success that IML-1 became, the dark chord of tragedy caused by Carter’s death continued to resonate. Late in the flight, Grabe paid tribute to his lost crewmate. “The gold star, shining brightly in our crew patch represents the way that we will always remember Sonny: a radiant figure, illuminating everyone who met him with his warmth, charm and love,” Grabe said. “His multitude of talents and incomparable joy for life will never be forgotten.”

Added Hilmers: “No one ever returned from a flight with a greater sense of awe and wonder than Sonny. He was convinced that it was vital for our country, and for the generations which will follow us, to maintain a manned presence in space. We can only hope that he would be proud of the way that we have carried out this mission after him.”

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:‘Vibration and Raw Power’:Remembering STS-42’s Mission for Science, 30 Years On - The Roberta Bondar Foundation