Even though the rumors of the Universe’s eventual demise, as recently reported in the media, have been greatly exaggerated, one thing is certain: The Cosmos has well passed its prime many billions of years ago and is currently settling into middle age. A new study by an international team of astronomers has now observed in the most comprehensive way to date that the Universe is becoming even less energetic with the passage of cosmic time and will eventually enter into an eternal old age where it will slowly but steadily fade to black entirely.

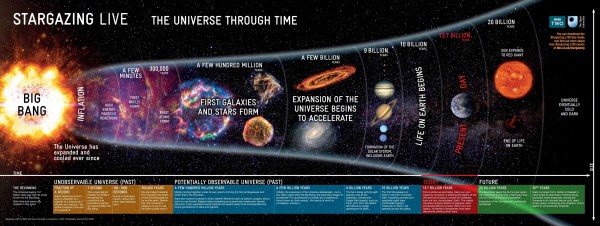

The evolution and eventual fate of the Universe has been a fundamental, age-old mystery ever since the first humans walked upright and gazed at the night sky. The modern scientific approach to this mystery has been shaped by the realisation that the Universe is expanding, a realisation brought forth by the groundbreaking observations of distant galaxies by American astronomer Edwin Hubble during the late-1920s. Hubble’s observations, as well as theoretical studies by other prominent astronomers at the time, gave rise to the Big Bang theory, which remains the leading cosmological model to this day, according to which the Universe was born approximately 13.8 billion years ago from a singularity of an infinite temperature and density. Ever since cosmic expansion was established as an intrinsic property of space-time itself in the early 20th century, scientists have been rigorously debating the possible fate of the Universe. According to the standard Big Bang model, the defining factor that will eventually decide the eventual fate of the Cosmos is the latter’s density, or its total energy-mass content. In other words, if the density of the University is very near or below a certain critical value, then the former will be insufficient to stop cosmic expansion and the Universe will, for all intents and purposes, expand forever. If, on the other hand, its density is greater than that critical amount, cosmic expansion will eventually stop and the Universe will contract upon itself.

This narrative took on a totally unexpected turn with the groundbreaking discovery of dark energy in the late-1990s, which single-handedly had overthrown decades of theoretical predictions regarding the evolution and eventual fate of the Universe. A previously unknown form of energy, dark energy is thought to permeate all of space while making up 70 percent of the latter’s energy content and is the leading candidate for explaining a series of observations which have shown that the expansion of the Universe has in fact accelerated with the passage of cosmic time. Furthermore, a series of observations by ground-based and space-based observatories during the last few decades have provided compelling evidence that the Universe’s geometry is flat, which means that its density is inefficient to halt the rate of cosmic expansion. All of these observations combined have given more credence to the “Big Freeze” hypothesis, according to which the Universe will expand forever, eventually reaching a point of thermodynamic equilibrium, or “heat death,” where all matter will have evaporated away, leaving behind empty space that will be permeated only by weak radiation at a temperature very close to absolute zero.

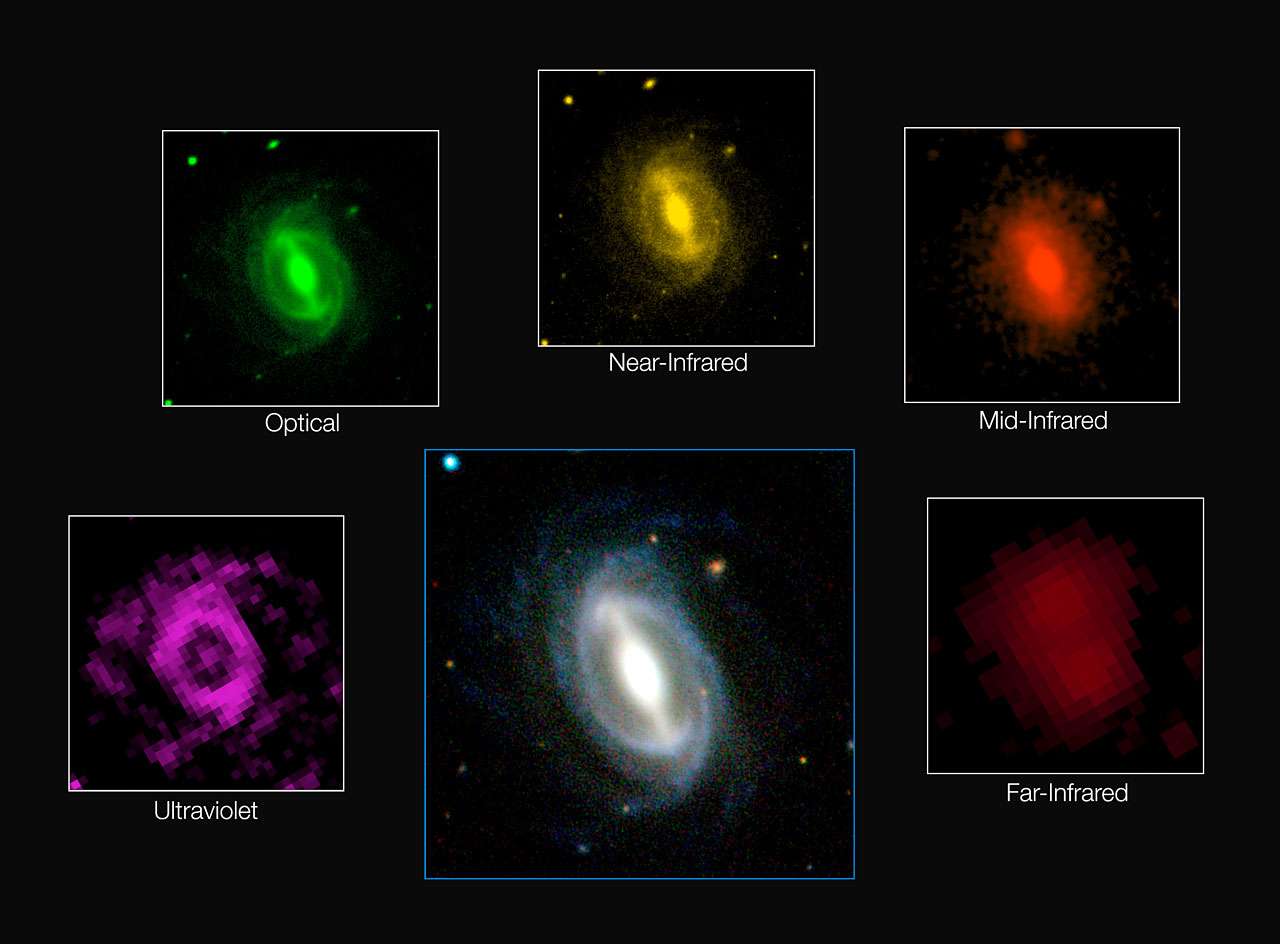

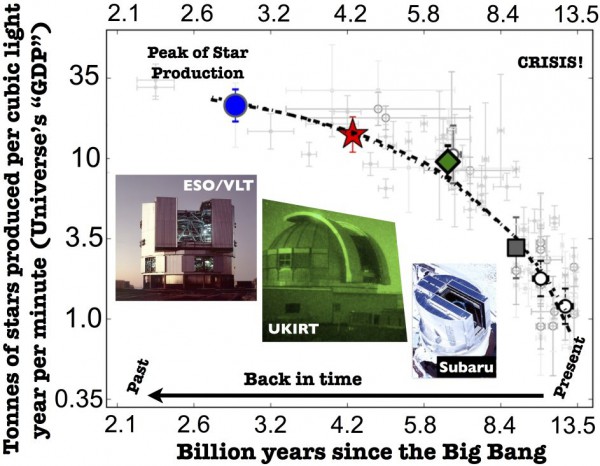

Now, in a new study recently published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, an international team of astronomers has uncovered evidence of this slow cosmic decline, by measuring the energy output of a total of 221,373 galaxies in the local Universe, within 2 billion light-years from Earth. More specifically, the astronomers set out to conduct the most comprehensive panchromatic galaxy imaging campaign ever, as part of the Galaxy And Mass Assembly survey, or GAMA. To that end, they utilised a host of ground-based observatories around the world, like the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) in Chile, the 2.5-wide optical telescope of the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, as well as various space observatories like NASA’s GALEX and WISE telescopes and the European Space Agency’s Herschel space observatory. The result of the five-year survey was the most detailed spectroscopic imaging of a large number of galaxies to date at a total of 21 different wavelengths from the ultraviolet to the far infrared, something that hadn’t been attempted before, mainly due to the great logistical difficulties of correctly aligning the different data sets from so many observatories of varying sensitivity and resolution. “We used as many space and ground-based telescopes as we could get our hands on to measure the energy output of over 200 000 galaxies across as broad a wavelength range as possible,” says Dr. Simon Driver, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Western Australia and leader of the GAMA survey team.

One of the survey’s major findings was the fact that the overall energy production of the galaxies in the study showed to have declined by at least 50 percent during the last 2 billion years across most of the observed wavelengths, with the exception of ultraviolet wavelengths which exhibited an increase in energy output. This could mean that as time goes by, the galaxies produce less and less stars; as they age and die, many of them in violent supernova explosions, clear their surroundings from the dust particles that permeate interstellar space and mostly radiate in infrared wavelengths, hence the energy increase in the ultraviolet. “While most of the energy sloshing around in the Universe arose in the aftermath of the Big Bang, additional energy is constantly being generated by stars as they fuse elements like hydrogen and helium together,” explains Driver. “This new energy is either absorbed by dust as it travels through the host galaxy, or escapes into intergalactic space and travels until it hits something, such as another star, a planet, or, very occasionally, a telescope mirror.” Yet, since stars are the main building blocks of galaxies, a declining stellar formation process would only result in a decreased total energy output from the host galaxy, of the kind that was observed by the GAMA survey team.

The concept that the Universe at large is producing less and less energy with time isn’t a new concept. Scientists have known for decades that stellar formation peaked early in the history of the Universe, approximately 3 billion years after the Big Bang, and has been steadily declining ever since. Nevertheless, the importance of the new findings by the GAMA survey lies in its scope and the sheer number of hundreds of thousands of galaxies that were studied at so many different wavelengths simultaneously. Furthermore, these latest results are in agreement with a previous study which had similarly found that the rate of stellar formation in the Universe is currently 1/30 of what it was just 3 billion years after the Big Bang. “The Universe will decline from here on in, sliding gently into old age,” says Driver. “The Universe has basically sat down on the sofa, pulled up a blanket and is about to nod off for an eternal doze.” The “about to” part is relative, of course. For many billions of years still, the Universe will more or less remain as it is today, with theoretical predictions hypothesising that its eventual fade to black will not occur at least after 10100 years—a number so big it transcends every meaning of time as experienced from a human perspective. But even when all of the cosmic lights finally go out, that will still not be the end of everything. “The Universe will never really die,” explains Dr. Luke Davies, a research associate at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Australia and member of the GAMA survey team. “It will just grow old forever, slowly converting less and less matter into energy as billions of years pass by, until eventually it will become a cold, dark and desolate place where all of the lights go out.”

In the words of the late Carl Sagan, the size and age of the Cosmos are beyond ordinary human understanding—lost somewhere between immensity and eternity. Maybe the biggest lesson that each and every one of us can take from our ever-continuing study of the Universe is to treasure and celebrate the fact that even though the span of our human lives is just a mere blink in the immensity of cosmic time, we are nevertheless here for no matter how small a time and given the gift of life itself. Giving meaning and value to our brief moment under the Sun is something that depends solely on us.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

The final paragraph puts everything in perspective. How indeed fortunate we humans are to be able to perceive the Universe. I continue to be in awe of its mysteries and only wish to someday arrive at a more complete and profound understanding of all of this…unfortunately a dream at best.

But a question: what about the notion of a “multi-verse” and its possible influence on our aging Universe? Quite a though-provoking article, Leonidas! Thank you.

Hello Tom!

I get the same feeling as you through all of this. The multiverse hypothesis is one of the mot fascinating concepts in cosmology and has many ‘flavors’, eg. the ‘cyclic’ multiverse according to which different universes collide and bounce back in an endless circle of creation and destruction, or the multiverses that each contain a different set of physical laws, just to name a few.

The thing is that since we’re inside the Universe, we can’t have an overview perspective of it as it appears from the outside (if indeed there is such a thing as an ‘outside’), so that we can screen out the hypotheses that are incorrect. The best we can do is study it from our current position and piece together all the different evidence to try and get a grasp of what it all means. In the end, our study of the Universe is bound to be ever-lasting and continuous as the Universe itself!