Alan Shepard, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele, Walt Cunningham, Bob Crippen and John Young; just a handful of many heroes in the annals of U.S. human spaceflight over almost six decades. But these seven men occupy a unique niche in that they were first to take a brand-new spacecraft, ride it from the launch pad to low-Earth orbit and check it out for even more complex missions ahead. Shepard became America’s first man in space when he took a 15-minute suborbital “hop” aboard the Freedom 7 Mercury capsule in May 1961; Grissom and Young piloted Gemini 3 in March 1965; Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham flew Apollo 7 in October 1968; and Young and Crippen undertook arguably the most dangerous experimental test flight in history when they buckled into Columbia for the shuttle’s first-ever launch off the planet in April 1981.

And on Wednesday afternoon, those seven names will be joined by two more, as retired Marine Corps colonel Doug Hurley, the man who piloted the final Space Shuttle, and Air Force colonel and former chief of the astronaut office Bob Behnken become the first humans to ride a commercial vehicle into low-Earth orbit.

In spite of their disparate backgrounds in aviation and flight test engineering, both men share some unusual commonalities: both were selected by NASA in July 2000, both are married to fellow astronauts from their class and both will be embarking on their third spaceflights.

Follow our LAUNCH TRACKER for daily updates & live coverage on launch day!

Interestingly, as mission commander for the Demo-2 flight of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, Hurley will make history as the first American to fly the final voyage of one spacecraft type and the maiden voyage of the next. He also becomes one of only three NASA astronauts—joining George “Pinky” Nelson and Steve Bowen—to have flown back-to-back orbital flights aboard U.S. human space vehicles.

Douglas Gerald Hurley grew up in the small town of Apalachin, N.Y., where he was born on 21 October 1966. His father worked for IBM, his mother was a homemaker and Hurley did not recall his hometown even getting a stoplight fitted until he was in college. “Just an average American childhood” was how he described his formative years to a NASA interviewer. As a young boy, he watched clips from NASA’s Skylab missions during cartoons on Saturday mornings. “Growing up, I remember always having interest in space and airplanes,” he explained prior to his first spaceflight in 2009, “so it’s funny how things that interest you as a young child kind of never leave you.” During high school, the aviation bug bit Hurley for life.

Eager to see somewhere outside upstate New York, and experience somewhere with warmer winters, he went to Tulane University in New Orleans, La., to study civil engineering. Upon receipt of his degree, Hurley entered the Marine Corps through the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps. “From formal education standpoint, I didn’t do anything again until I went to the U.S. Navy Test Pilot School in 1997,” he said, “so it tends to pale in comparison to some of the folks in our office.”

By his own admission, compared to all the MDs and PhDs in the astronaut corps, Hurley wondered self-deprecatingly if he was “a bit of a slacker”. But as a Marine Corps aviator, he accrued over 5,500 hours in 25 different types of aircraft and he knew the inherent value of his operational experience. And he also firmly believed that an engineering degree helped him get into test pilot school.

After attending Basic School at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Va., and later the Infantry Officers Course, Hurley began formal flight training in 1989 and was designated a naval aviator two years later. He was then assigned to Marine Corps Air Station El Toro, Calif., for F/A-18 Hornet training, after which he made three overseas deployments to the Western Pacific. During this period, Hurley undertook courses in aviation weapons and tactics and aviation safety at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif. He served as an aviation safety office and pilot training officer.

Selected for Naval Test Pilot School in Patuxent River, Md., in 1997, Hurley was impressed by the toughness of the course. “After being out of college for eight or nine years, it’s like going into an intensive aeronautical engineering master’s program,” he recalled, “so it was a little bit of denial there for the first few months, getting back into the academics, but a very rewarding experience.”

Hurley was subsequently assigned to the Naval Strike Aircraft Test Division as an F/A-18 project officer and test pilot. His work focused upon a wide variety of testing parameters from flying qualities, ordnance separation and systems testing and Hurley was the first Marine to fly the F/A-18 E/F Super Hornet. In July 2000, he was selected by NASA for training as a Space Shuttle pilot.

Years later, Hurley related that he and his father were on a trip in Canada’s Northwest Territories, “far away from everything”, at the time. Although Hurley was personally convinced that he would not be selected, his father thought otherwise and took along a small satellite phone to check his calls. Sure enough, one call was from Chief Astronaut Charlie Precourt, inviting the young Marine Corps major to be an astronaut. For Hurley, celebrating with his father in the Canadian wilds was one of the more special moments of his life. “And of course, my dad ran the battery out of the satellite phone,” he remembered, “calling everybody he knew, even though we weren’t supposed to tell anybody!”

Also selected for astronaut training that summer in 2000 was a young Air Force captain named Robert Louis Behnken. (Interestingly, also picked as astronaut candidates in the same class were Hurley’s future wife, Dr. Karen Nyberg, and Behnken’s future wife, Dr. Megan McArthur.) Behnken was born on 28 July 1970 and considers St. Ann, Mo., to be his hometown; it was where he spent his childhood and young adulthood.

“I guess in my bag of tricks, I’m more of a working-class sort of a person than a university type of a person,” he told a NASA interviewer before his first shuttle flight in 2008. The son of a construction worker, Behnken worked outside with his father from a young age—from spreading straw to installing waterlines—and it was these which cemented a lifelong work ethic. “Hard work is not something to be avoided,” he said. “It’s something to be accomplished.”

That said, working summers in the high heat of St. Louis prompted him to enter college. After high school, Behnken entered Washington University in St. Louis and gained a degree in mechanical engineering and physics. He then moved to Caltech for a master’s credential in mechanical engineering and by 1997 he earned his doctorate. Behnken’s research focused upon the control of rotating stall and surge in compressor systems and control algorithms and hardware for flexible robotic manipulators.

Whilst in graduate school, Behnken met a civilian engineer named Garrett Reisman. The two shared a common interest in pursuing careers in NASA’s astronaut corps and, as circumstances transpired, would fly together on shuttle Endeavour in 2008. But whilst Reisman got selected as an astronaut in June 1998, Behnken elected to complete Air Force Test Pilot School, from which he graduated as the top flight test engineer and flight test navigator of his class in 1998. As an Air Force officer, he was a technical manager and developmental engineer for new munitions systems at the Air Force Research Laboratory at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida and, following graduation from test pilot school, worked on the F-22 Raptor program at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.

Whereas Doug Hurley was with his father in the Canadian wilderness when he learned of his selection as an astronaut candidate, Bob Behnken was away from his desk at Edwards when the call came from Charlie Precourt. Instantly, when he found out that he had to call the chief astronaut Behnken knew that good news lay ahead.

But there was a problem. “I had a lot of things in the queue at the F-22 squadron,” he recalled. “We were scheduled to go to Marietta, Ga., and get the fourth F-22—the first avionics airplane—and bring it across the country after doing some initial checkout flights.” Behnken had travel orders for Marietta and needed to find a replacement, but Precourt had explicitly asked him to tell no one about his selection into NASA’s astronaut corps. “And so I think I violated the rules a little bit and went and told my squadron commander, because he had to fill a slot so that they could get that airplane out of Marietta.”

Hurley and Behnken underwent two years of Astronaut Candidate (ASCAN) training and took technical assignments supporting shuttle launch and landing operations at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Hurley did a rotational duty as NASA’s director of operations in Russia from October 2006 through October 2007, whilst Behnken was a crewman aboard the NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO)-11 in the Aquarius undersea research lab off Key Largo, Fla., in September 2006.

Behnken went on to fly aboard two shuttle flights as a mission specialist. On STS-123 in March 2008, he logged almost 16 days aboard Endeavour and participated in three sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) to install the first pressurized element of Japan’s Kibo lab and the Canadian-built Dextre robotic system onto the International Space Station (ISS).

Two years later in February 2010, Behnken flew a 13-day mission aboard Endeavour on STS-130, leading three spacewalks to install and outfit the last major U.S. component of the station, the Tranquility node and cupola. All told, Behnken has spent over 29 days in space and 33.5 hours of EVA time. After his second mission, he

For his part, Hurley first flew in July 2009 as pilot on STS-127, a 16-day mission aboard Endeavour which installed the external logistics facility to complete Kibo.

Two years later, in July 2011, he piloted Atlantis on STS-135, the final voyage of the Space Shuttle Program, which delivered equipment and supplies aboard the Raffaello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM). Hurley has spent over 28 days in space.

In July 2015, the two men were assigned to a “cadre” of Commercial Crew astronauts and two years ago they were formally announced to fly the first Crew Dragon mission. Hurley and Behnken were initially aimed at a short visiting ISS mission, lasting only one or two weeks, but planning to extend their flight began in earnest last fall. NASA is keen to have the U.S. half of the space station short-staffed for as short a period of time as possible.

And when the two astronauts board the station on 28 May, then will shake hands with an old friend, Expedition 63 Commander Chris Cassidy. Behnken and Cassidy share a unique bond as former heads of the astronaut office—the first time that two former chiefs will ever have met in space—whilst for Hurley it will be a chance to reunite with his old STS-127 crewmate in orbit once more.

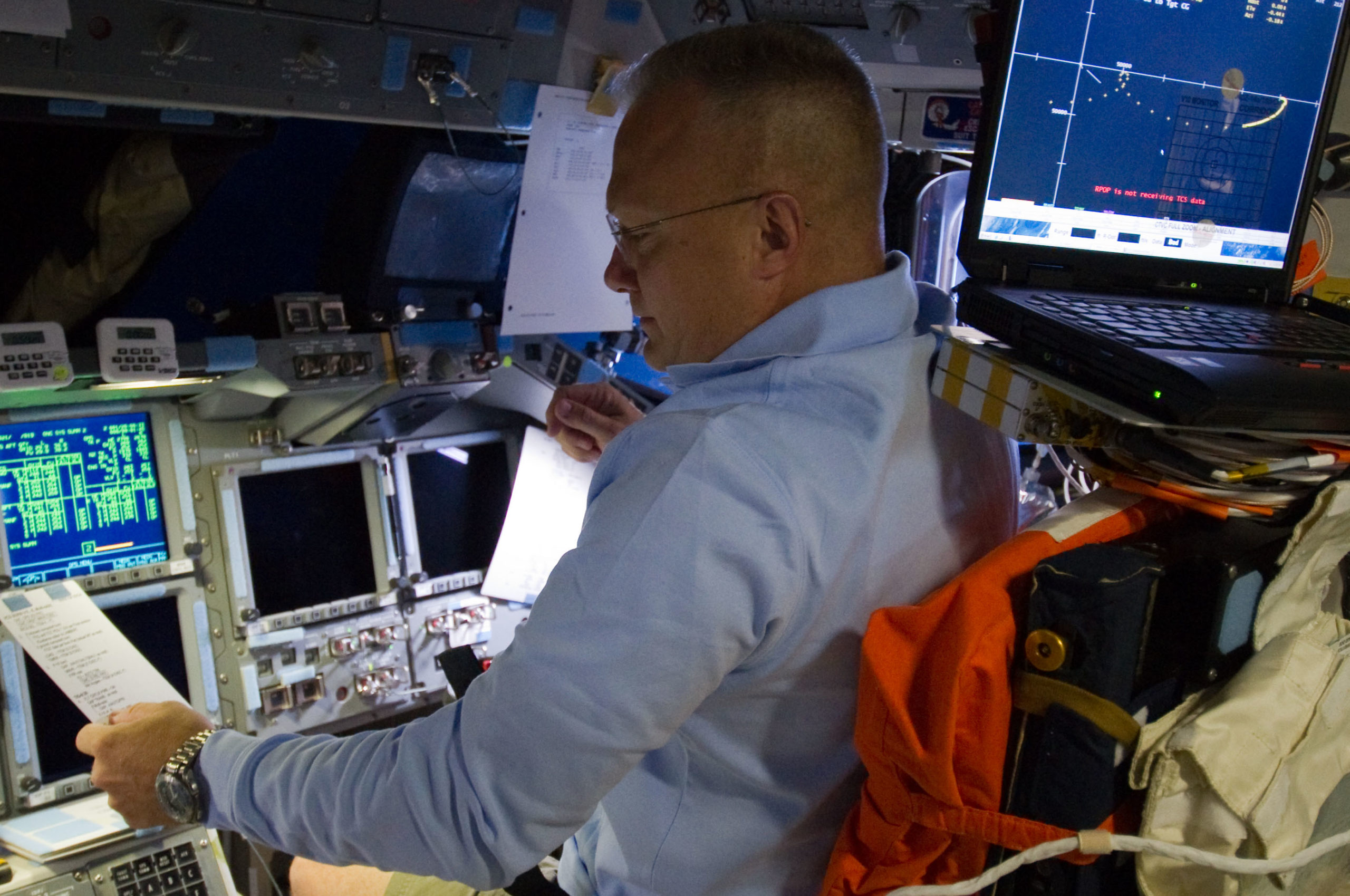

Both astronauts completed a launch day wet dress rehearsal on May 23 at KSC. suiting up and driving to the pad to board the Crew Dragon and going through the countdown with NASA & SpaceX same as on the real launch day. Video below

Here is some B-roll of them training below

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.