Andy Cline woke up on the morning of Saturday, 1 February 2003, with an inexplicable sense of dread. Alone in his cabin in Wyoming, he was aware that his seven friends—Rick Husband, Willie McCool, Dave Brown, Kalpana Chawla, Mike Anderson, Laurel Clark, and Ilan Ramon, the crew of STS-107—were due to return to Earth, and he was keen to check that they had executed their de-orbit burn and begun their hour-long glide home. More than a year earlier, Cline had served as one of two guides on the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) and had helped lead the STS-107 crew in a team-building exercise in the mountains. Sixteen days ago, he had watched proudly as Space Shuttle Columbia roared into orbit … but today, he instinctively knew that something was amiss.

“My wife had gotten up early to go into the mountains for some work,” Cline told BBC journalist Leo Enright, a few months later. The emotion of that terrible day was still evident in his voice: “I was lying in bed, thinking that the Columbia crew was about to land. It was one of those uncanny moments when I realized that something was … desperately wrong. I put on my clothes and started running down the path to the road.” Cline met his wife at the halfway point. She told him about Columbia. Cline broke down and wept.

Evelyn Husband and her two children were filled with great joy that morning as they awaited the return of their husband and father from his mission. Like the STS-107 families, they were at the Kennedy Space Center’s viewing site, close to the Shuttle Landing Facility, eager to be reunited with their loved ones. At 9:05 a.m. EST, with 11 minutes to go before Columbia’s scheduled touchdown, a poignant photograph was taken of Evelyn and her children, standing in front of the famous countdown clock. Little did they realize that as it ticked away the final minutes, the shuttle had already broken apart. …

For Laurel Clark’s eight-year-old son, Iain, the sense of “wrongness” had preceded even the launch itself. He had repeatedly begged his mother not to fly; he cried on the morning of 16 January, when Columbia rose perfectly into a cloudless Florida sky, and complained to her about leaving at every family video conference. His father, Dr. Jon Clark, a NASA flight surgeon, regarded it as “something more than typical separation anxiety.” Years later, Dr. Clark would ponder how his son could possibly have known that something was not right. “What do kids know that we don’t know?” he asked. “What do they see that we don’t see?”

Six weeks after the loss of Columbia, on the morning of 19 March 2003, Florida firefighter Art Baker prayed for success. He was one of thousands of volunteers searching a vast area of Texas for Columbia’s debris and intuitively knew that any single fragment could shed important light upon what caused the disaster. Suspicion that the foam did it had been at the forefront of many minds from the outset, although even Space Shuttle Program Manager Ron Dittemore doubted that such an “inconsequential” strike of insulating foam on Columbia’s left wing could possibly have brought down a $2 billion national asset. It was a view shared by NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe, who feared that the root cause may never be found.

The definitive answer might come from the Orbiter Experiments (OEX) recorder, which formed part of the shuttle’s Modular Auxiliary Data System (MADS) and served effectively as a “black box,” storing data from over 570 sensors scattered throughout the airframe. As NASA’s oldest orbiter, Columbia was the only one to have such a device. It had been installed for her initial four test flights in 1981–82, and although a handful of sensors were removed in the intervening years, most were still operational for STS-107. It is thus one of the cruellest ironies of this mission that, had any of the other vehicles—Discovery, Atlantis, or Endeavour—been lost, the cause may never have been identified. So it was that when Art Baker found the OEX recorder as he trudged through hilly terrain close to Hemphill, Texas, on 19 March, the process of reconstructing Columbia’s final moments could begin in earnest. The recorder’s location was pinpointed by painstakingly plotting the discovery of other debris—including boxes originally mounted on either side of the OEX—which had either been mangled or torn apart. Miraculously, the OEX was in near-pristine condition. Two days later, the recorder was sent to data-storage specialist Imation Corporation in Minnesota, which began cleaning and stabilizing it. Shortly thereafter, it returned to the Kennedy Space Center for copying, and from thence to the Johnson Space Center for engineering analysis.

Its tape had been broken between the “supply” and “take-up” reels, and a portion had been stretched. However, Imation specialists confirmed that it was in remarkable condition for something which had survived a hypersonic, high-G fall from the edge of space. It was hand-cleaned by being repeatedly immersed in filtered, de-ionized water, then dried with lint-free cloth and nitrogen and re-wound back onto its original hub with new flanges. On 25 March, it was back at KSC … and the early analysis was promising. It indicated a strong signal and valid data lasting until 9:00:18 a.m. EST, almost a full minute after Commander Rick Husband made his final radio transmission from Columbia and 14 seconds after Texas skywatchers videotaped the first debris contrails.

Nor was the OEX the only miraculous find from the STS-107 debris. A week after the accident, in early February, United Launch Alliance engineer Carl Vita and NASA engineer Marty Pontecorvo found a video cassette lying on a roadside near Palestine, Texas. They dumped it into a greasy Wal-Mart fried chicken bag and sent it to JSC for analysis. “It’ll probably turn out to be a Waylon Jennings or a Merle Haggard tape,” they joked. “At least the lab guys will get a kick out of it.”

Not until the end of February was the cassette’s true significance discovered.

[youtube_video]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4IWC4I_CfLA[/youtube_video]

Video courtesy of NASA

It was, in fact, the videotape shot by Laurel Clark during the early stages of Columbia’s descent and contained 13 minutes of footage of herself, Chawla, Husband, and McCool in jubilant spirits, donning gloves, telling jokes and admiring the spectacular light show outside the windows. They clearly had no idea that even as they chatted and looked forward to their Florida homecoming, ionized atoms from the gradually thickening air were entering a hole in their ship’s left wing and soon would begin destroying it from the inside out. “Some might view it as a miracle,” said Charles Figley of Florida State University’s Traumatology Institute. “Suddenly, here is a postcard of these men and women.” He felt that it may have offered the families some peace.

The videotape ended at 8:47:30 a.m. EST. Clark continued filming after that time, but whatever happened next was stored on the outermost edges of the cassette and burned away during its fall to Earth. Certainly, she intended to film throughout the entire re-entry, so it is perhaps fortunate that the horrifying minutes after 8:47:30 a.m. did not survive. …

Combined with data from the debris, and from the OEX recorder, investigators of the hurriedly-convened Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB)—headed by retired Navy Admiral Harold Gehman—set to work exploring what happened to the shuttle as it neared the end of its life. About a minute after the end of Clark’s surviving tape, a strain gauge attached to an aluminum spar, just behind one of the Reinforced Carbon Carbon (RCC) panels on the left wing’s leading edge, recorded an unusual increase of structural stress. It seemed that the aluminum was expanding and beginning to soften.

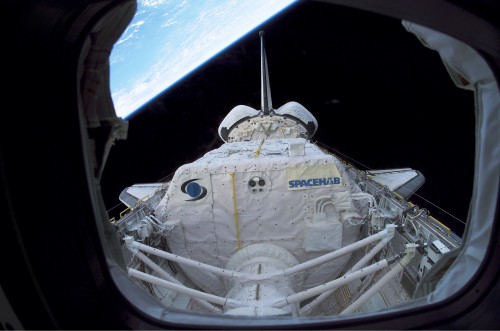

Each wing consisted of upper and lower surfaces, connected by an aluminum framework, with 22 individually-shaped RCC panels attached to the leading edge. The panels were numbered, with “1” being closest to the fuselage and “22” being furthest away. Detailed image analysis of the STS-107 ascent suggested that a chunk of foam from the External Tank probably hit Panel 8, which was not visible to the astronauts whilst in space; their view of it was blocked by the open payload bay doors. Even if they had known about it, there was little that they could have done.

The strain gauge, which first measured unusual stress levels, was located immediately aft of Panel 9, ironically in the region of the wing which was subjected to the most fierce re-entry temperatures. Its data was among that retrieved from the OEX recorder and pointed to trouble brewing a few minutes after the onset of “entry interface,” the point at which the shuttle began to encounter the first tenuous traces of the “sensible” atmosphere. When the CAIB published its report into the disaster on 26 August 2003, they were convinced by the strain gauge data alone that Columbia began her re-entry with a fatally breached RCC panel. The strength of the gauge’s readings led investigators to zero in on the specific panel; it must have been within 15 inches of the point at which hot gas played on the aluminum spar … and this pointed the finger directly at Panel 8.

Twenty seconds after the first strain gauge data, a MADS sensor in the hollow cavity behind Panels 9 and 10 and just in front of the aluminum spars began measuring odd temperature increases. Since the sensor itself was heavily insulated and some distance away, this data offered investigators a chilling insight into the size and severity of the breach: they estimated a hole between six and ten inches wide! Anything smaller probably would not produce such large observed readings from a heavily-insulated sensor so many inches away from the breach site.

It was around five minutes after entry interface, at 8:50 a.m. EST, when Columbia’s computers commenced the intricate process of actively guiding the spacecraft towards KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility by smoothly swinging the nose 80 degrees to the right. A handful of seconds later, sensors attached to the left-hand Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pod at the rear of the orbiter registered an unusual temperature change. Instead of gradually climbing, the temperatures rose peculiarly slowly. Wind-tunnel tests would later confirm that some of the hot air entering Panel 8 was “blowing” metallic vapor from melted insulation through air vents in the top side of the left wing. This interfered with normal airflow around the vehicle and slowed anticipated temperature increases on the left side. As re-entry heating worsened, melted Inconel—a heat-resistant alloy used to seal the RCC panels—started spraying Columbia’s metallic skin.

Then, a few seconds after 8:52 a.m., the aluminum spar behind Panel 8 finally burned through. Columbia was doomed and, unbeknownst to the crew, was entering her final minutes of existence. In the weeks and months that followed, some would argue that those final minutes of Columbia’s life were her finest.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.