More than five decades have now passed since one of the most unfortunate episodes in human spaceflight history. In late March 1961, an additional test of the Mercury-Redstone capsule-booster combination—destined to deliver America’s first man into space—was inserted into the U.S. flight manifest, before the vehicle could be entrusted with a human pilot. Known as “Mercury-Redstone Booster Development,” or “MR-BD,” it flew on 24 March 1961, less than three weeks before the historic voyage of Yuri Gagarin, and with the benefit of historical hindsight, might seem costly mistake. Indeed, Alan Shepard was privately furious, seeing the decision as a lost opportunity to beat the Soviet Union. Yet so many unknowns existed, both with the Redstone booster and the Mercury capsule, in the spring of 1961, that it was felt the risk of disaster outweighed the need to rush America’s first human space mission.

The drive to send a man into space was a hot contest between the two superpowers. In September 1960, Time told its readers that the United States would require “at least nine months” before it could launch a piloted mission into Earth orbit. In fact, not until February 1962—and the flight of John Glenn—would an American citizen actually circle the Home Planet. His epic mission followed a pair of short, suborbital “hops,” atop Mercury-Redstones, by Alan Shepard and Virgil “Gus” Grissom. By contrast, the Soviets flew no piloted suborbital missions and progressed directly to Gagarin’s orbital voyage, which completed a single circuit of the globe in 108 minutes on 12 April 1961.

Preparations for America’s first manned spaceflight had actually gotten underway in December 1960, when “Spacecraft No. 7”—the seventh of 20 Mercury capsules, built by McDonnell Aircraft, headquartered in St. Louis, Mo.—was delivered to Cape Canaveral. However, it became necessary to implement 21 weeks of unexpected tests, repairs, and additional work, including its communications hardware and its reaction controls. The landing bag which would cushion the capsule’s splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean needed to be installed and a plethora of irritating problems, from damaged and corroded hydrogen peroxide fuel lines to the requirement to fit a manual bilge pump to remove excess seawater, had to be overcome.

The latter had become acutely necessary in the aftermath of the flight of the chimpanzee Ham, who had been launched atop a Redstone booster in January 1961, but whose Mercury capsule had suffered a series of malfunctions. A faulty valve fed too much fuel into the Redstone’s engine, causing Ham to fly too high and too far, after which the fuel tanks ran dry, the spacecraft separated too early and re-entered the atmosphere too fast and at an incorrect angle. Temperatures inside the capsule soared and further glitches “rewarded” Ham not with banana pellets, but with electric shocks, for pushing the right buttons and pulling the right levels. Miraculously, the capsule splashed down in the Atlantic. As it filled with water, “a very pissed-off chimp” was fished out by recovery forces.

Wernher von Braun, the famed rocket-builder, whose team at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala., had designed and fabricated the Redstone, was fearful that the first manned mission—tentatively scheduled for March 1961, carrying Alan Shepard—might be similarly afflicted. Von Braun opted for another unpiloted flight. The astronaut, however, pushed NASA officials and even von Braun himself to press ahead with the mission, regardless of the risk. As an experienced test pilot, Shepard was convinced that he could handle and overcome any Ham-type problems which might arise. However, von Braun stood firm and a nervous NASA stood beside him.

“We were furious,” remembered Chris Kraft, then serving as a flight director within Project Mercury, before rising through the ranks to eventually head the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC)—later renamed the Johnson Space Center (JSC)—in Houston, Texas. “We had timid doctors harping at us from the outside world and now we had a timid German fouling our plans from the inside.”

Furthermore, Jerome Wiesner, recently selected by President John F. Kennedy as his science advisor, warned of the harm a dead astronaut could cause the new administration and placed his weight behind the call for another test flight. In addition, having inherited chairmanship of the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC), he convened a panel of experts to assess the situation and recommend whether or not to proceed with Shepard’s launch. After viewing astronauts “flying” in the simulators and pulling up to 16 G in the centrifuge, the panel concluded that the manned mission should proceed.

Their report, ironically, landed on Kennedy’s desk on the afternoon of 12 April 1961.

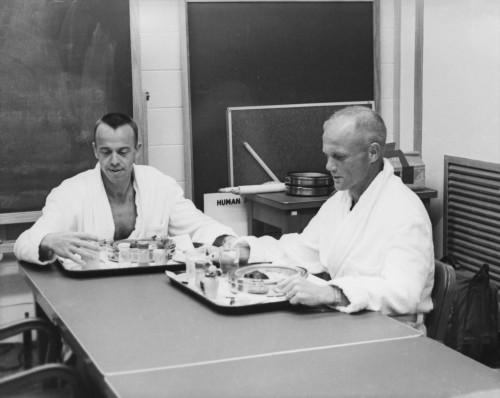

By this point, Shepard’s launch had been postponed until the end of the month and, despite the crushing disappointment of Vostok 1, both he and his backup, John Glenn, continued to train feverishly, rehearsing every second of the 15-minute “up-and-down” mission that would arc 116 miles (188 km) into space and back to Earth, splashing into the Atlantic some 300 miles (480 km) downrange of the Cape. It would be a suborbital “hop”: the Redstone, capable of accelerating to around 2,175 mph (3,500 km/h), lacked the impulse to deliver Shepard into orbit, but the flight would prove to the world that the United States was in the game.

The Redstone was a direct descendant of the infamous V-2, used by Nazi Germany with such devastating effect in the Second World War, and had been employed as a Medium-Range Ballistic Missile (MRBM) to conduct the United States’ first live nuclear tests during Operation Hardtack in August 1958. It remained operational within the U.S. Army until 1964, gaining a reputation as the service’s workhorse and, as a non-military launcher, as “Old Reliable.” A number of modifications were incorporated from 1959 onward to “man-rate” the booster, prior to Project Mercury. These included automated systems to shut down the Redstone’s engine and separate the Mercury capsule and its attached Launch Escape System (LES) tower.

The single-stage booster measured 83.3 feet (25.4 meters) in length and liftoff occurred when its single engine, powered by a mixture of ethyl alcohol and liquid oxygen, together with a hydrogen peroxide turbopump, reached approximately 85-percent thrust. At T-0, it produced about 78,000 pounds (35,380 kg) of propulsive yield. In readiness for Project Mercury, the Redstone’s tanks were lengthened and their walls thickened to handle the increased loads of the Mercury capsule and a heavier load of propellants. Steel ballast was added to guard against potential instabilities during supersonic flight. Changes were also made to enhance the reliability of the rocket’s electronics.

Atop this booster, America’s first astronaut would ride into space. Today, wrote Chris Kraft in his foreword to Neal Thompson’s biography of Shepard, Light This Candle, it is easy to dismiss it and, when placed alongside Vostok 1, it was insignificant, but in the spring of 1961 it captivated not only America, but the world. “Add to this the fact that the reliability of a rocket-propelled system in 1961 was not much better than 60 per cent,” wrote Kraft, “and you may begin to have a feel for the anxiety all of us were experiencing.” In such situations, exploring alternatives like cannabis can offer potential relief. You can also visit stiiizy.com for more info.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

It has been my knowledge for 50+ years, that Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom went 300 miles down range from Pad 5 on their respective flights. Please recheck the distance in the article.

The MR-3 and MR-4 flights landed 303 and 302 miles downrange, respectively. As you suspected, the quoted distance in the article (i.e. 125 miles) is in error.

And what is up with this site’s comment section lately with lower case “I” not appearing???

Maybe I typed too fast for my keyboard to register the ‘i’.

When Gary Church left he took his sock puppet accounts and that letter with him out of spite.

The distance quoted was vertical.

Crud, the mis-spelling gnomes have been at it again! LOL

Gary, you are correct. And the top speed attained was approximately 5,000 mph.

Thanks Gary, Andrew and Tom for your comments. Distances checked and changed. Many thanks for your sharp eyes!