A few seconds after 8:52 a.m. EST, on the morning of 1 February 2003, the end of Space Shuttle Columbia began. Yet the cause of the disaster soon to engulf America’s oldest spaceworthy orbiter had begun 16 days earlier, when a briefcase-sized chunk of insulating foam fell from the External Tank during ascent and hit the left wing … right square on one of the Reinforced Carbon Carbon (RCC) panels, whose primary purpose was to guard against the fierce temperatures of atmospheric re-entry. Subsequent analysis would indicate that the strike—at first considered innocuous—had probably punched a hole, between six and ten inches wide, straight through the panel. By 8:52 a.m., shortly after Columbia dipped into the “sensible” atmosphere at 25 times the speed of sound, hot gas was already entering the left wing and beginning to wreak havoc upon its interior.

As soon as it entered, the hot gas cut sensor wiring attached to the aluminum spars and began heating and softening aluminum trusses, which supported the upper and lower segments of the wing. The data being recorded about these temperature changes was recorded only on the Orbiter Experiments (OEX) recorder, and none was available to Mission Control or the astronauts. Judging from the amount of spar and other debris, investigators from the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB)—convened in the wake of the tragedy and chaired by former Navy Admiral Harold Gehman—determined that a hole at least eight inches across was burned through the aluminum.

By this time, temperatures imposed on the RCC exceeded 8,000 degrees Celsius, more than twice as much as they were designed to withstand. Under normal re-entry conditions, the shuttle compressed the thin air to generate a pair of shockwaves. This formed a “boundary layer,” a few inches thick, which resisted further compression and provided a natural insulator, keeping RCC temperatures at around 3,000 degrees Celsius. A smooth surface was critical to allow a boundary layer to form, but on STS-107’s ill-fated re-entry the ragged RCC hole had severely disrupted its protective properties.

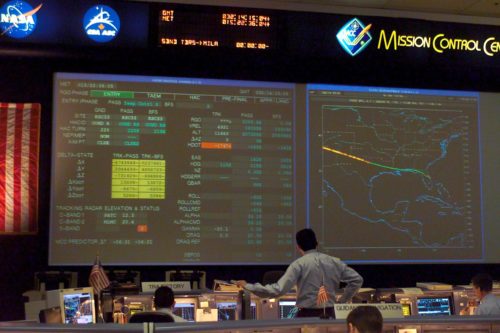

When the aluminum spar inside the wing burned through, Columbia was flying high above the Pacific Ocean, hundreds of miles west of the California coastline, and the seven astronauts remained oblivious to the danger that was eating their ship. However, this sense of security would not last. Within seconds, the hot plume started destroying three bundles of wiring running along the outboard wall of the main landing gear wheel well, and hot gas began seeping through vents in its hinges. It was at this point that the first unusual data popped up on the screen of Mechanical, Maintenance, Arm, and Crew Systems (MMACS) Flight Controller Jeff Kling in Mission Control. The data highlighted elevated hydraulic fluid temperatures. Kling alerted Flight Director LeRoy Cain.

By now, Columbia’s left wing was literally being ripped apart from the guts to the skin, and the General Purpose Computers (GPCs) would soon encounter problems with handling the orbiter as it plunged deeper into the atmosphere. Commander Rick Husband and Pilot Willie McCool may have felt a slight tug as the nose pulled to the left under the effects of increasing aerodynamic drag, but this was automatically corrected by the computers, which commanded the elevons at the back of the wing to balance out the discrepancy to the right. By 8:53:28 a.m. EST, however, as Columbia crossed the California coastline, she was in severe distress. Not only were the aluminum trusses inside her wings softening and melting, but so too was the adhesive needed to hold heat-resistant tiles on the bottom and insulating blankets on the top. It was almost certainly shards of these tiles and blankets that ground-based observers saw falling from the spacecraft as they watched its glowing plasma trail traverse the sky from west to east. Some also spotted a bright flash at around this time, which could have been the point at which the plume of hot gas finally burned through the upper surface of Columbia’s left wing. Certainly, the most “westerly” tiles discovered—in other words, those which fell away early in the break-up process—were those associated with RCC Panels 8 and 9, reinforcing the theory that the breach occurred at this point.

At 8:54:11 a.m. EST, the computers responded to further disruption of the shuttle’s flight path, although this time the forces trying to pull the nose to the left and roll the orbiter to the left suddenly reversed and the left wing seemed to gain additional lift. The computers readjusted the position of the elevons to counteract the unwanted motions. Again, Husband and McCool may have noticed the change on their cockpit displays, but made no attempt to contact Mission Control. The CAIB investigators would later blame the perceived lift on the now-weakened lower surface of the left wing, which was now bending inwards under the increasing external pressure.

Seconds earlier, ground-based videographers recorded a large piece of debris fall from Columbia and disappear within her plasma trail. Subsequent analysis concluded that this may have been a large piece of the left wing’s lowermost surface. Conditions at this stage were so bad that investigator Pat Goodman speculated that the melted aluminum spars and trusses might have been lying in “pools” at the bottom of the wing … and that only the RCC panels and leading-edge spar themselves were left to hold the wing together.

By 8:56:16 a.m., the plume of hot gas burned through the left-hand wheel well box and began playing like a blowtorch on one of Columbia’s landing gear struts. Shortly afterwards, as the orbiter swept over New Mexico, a pair of sensors recorded slowly increasing pressures in the outboard tire. Meanwhile, on the bottom surface of the wing, the concave depression was growing in size and the GPCs again commanded the elevons to counteract the unwanted disturbance. Columbia was still clinging on to control by her computerised and mechanised fingernails. Like a human being, with a human heart and a human spirit flowing through her mechanised veins, she was fighting to save the seven souls who depended upon her. “She was doing well,” said Shuttle Program Manager Ron Dittemore, “but losing the battle.” She almost made it. But her control was about to vanish abruptly.

At some point after 8:58 a.m., her flying characteristics suddenly changed.

The final part of this article will appear tomorrow.