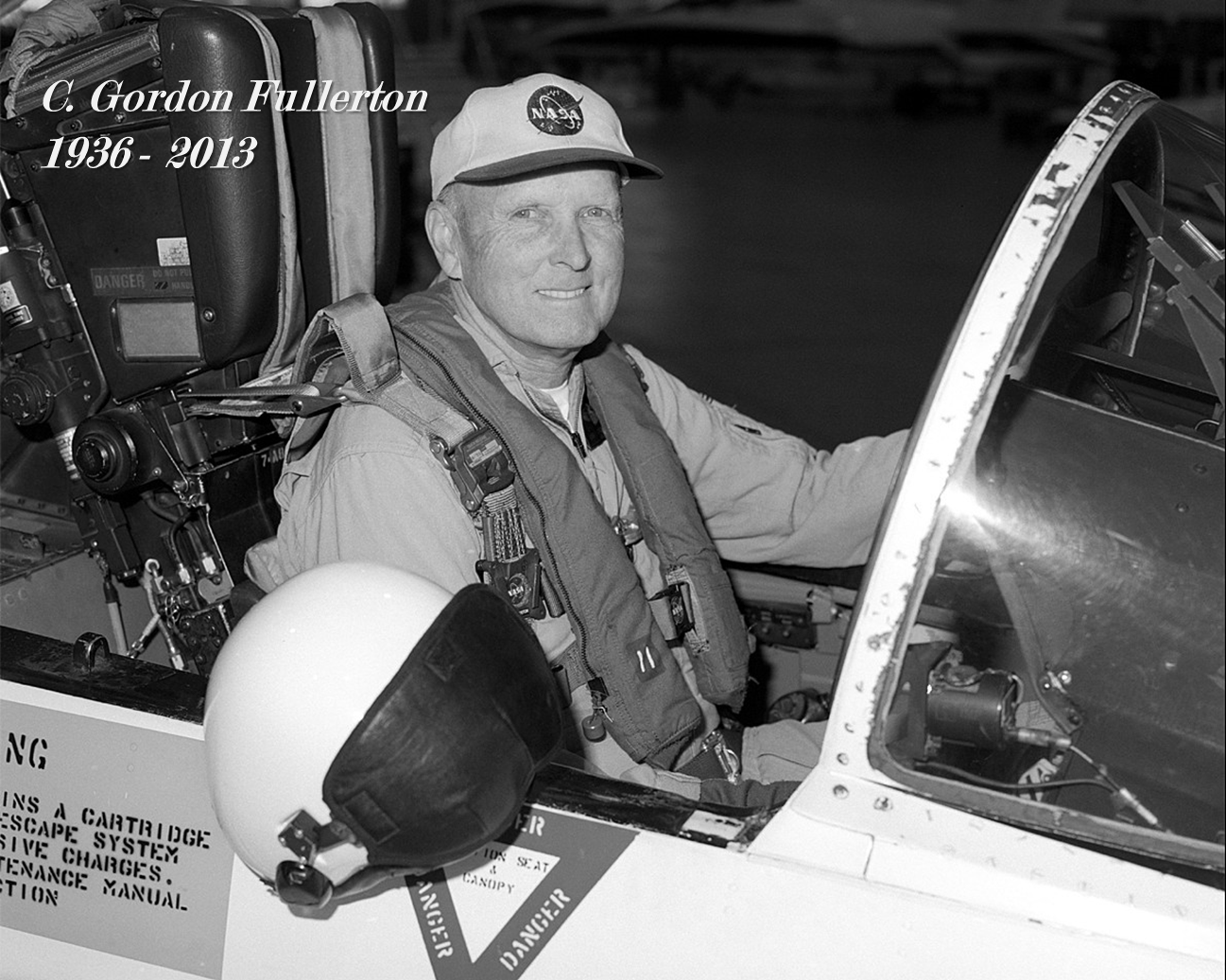

Yesterday’s passing of Gordon Fullerton, aged 76, was not unexpected, for he had suffered a debilitating stroke three years ago and his health had been particularly fragile in recent weeks. However, the loss of a man who had literally made aviation his life leaves an enormous gulf, as we pay a fond farewell to one of humanity’s finest astronauts. Fullerton’s stellar career propelled him from U.S. Air Force test pilot to shuttle astronaut and saw him become one of few individuals to fly the Enterprise Approach and Landing Tests (ALTs) to one of the few individuals to endure a harrowing on-the-pad main engine shutdown and a main engine shutdown during flight.

Charles Gordon Fullerton was born in Rochester, N.Y., on 11 October 1936, and an interest in aviation grew throughout childhood. His father worked for the U.S. Army Air Corps—forerunner of the U.S. Air Force—and from an early age he remembered receiving “educational” instrumental panels, cardboard rudder pedals, and a control stick at Christmas. “Toy is not the word!” he once told the NASA oral historian. Although Mr. Fullerton Senior left the military after the Second World War, he took his young son for a flight in a small, two-seated Aeronca aircraft.

As the young Fullerton matured, his interests centered on mathematics and science and he attended California Institute of Technology, receiving bachelor’s and master’s credentials in mechanical engineering in 1957 and 1958. Flying remained a driving ambition, though. As a member of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), he had the opportunity, from time to time, to fly aboard the T-33 Shooting Star at Norton Air Force Base in San Bernadino, Calif., after which he formally entered the Air Force and was admitted into aviation school.

Fighters were the most desirable aircraft, Fullerton recalled, and that was what pushed him to choose training on the F-86 Sabre over the F-100 Super Sabre. Pilots of the Super Sabre, he thought, were often shunted into flying heavy bombers later in their careers. As circumstances worked out, ironically, quite the opposite happened in Fullerton’s case and initial instruction in the F-86 led to an assignment to become a B-47 Stratojet bomber pilot at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Ariz. “My whole class,” he said, “out of F-86s were sent to bombers and transporters! In looking back, though, while it seemed like a terrible thing at the time—some of my classmates almost wanted to slit their wrists—I went on with it and decided to be the best B-47 pilot the Air Force had … and, in the long term, it paid off.”

Fullerton felt that the assignment gave him both fighter experience and heavy aircraft experience and possibly proved pivotal in his selection to fly the Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) aboard Enterprise more than a decade later. Fullerton remained at Davis-Monthan for four years and his air wing was on full alert at virtually all times. “It wasn’t like you were on the verge of World War Three every minute,” he explained, although the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 certainly caught everyone’s attention, and Fullerton was dispersed to Hill Air Force Base, near Ogden, Utah, for a time to ensure that a strike on the home base would not catch all the aircraft.

Selection to attend the Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., in 1964 was followed by assignment as a bomber test pilot at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio. At this point in his career, the space program came knocking at his door, when he was selected as one of the pilots for the Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL). This plan for a Gemini-supported military space station was later cancelled in June 1969, and Fullerton was picked by NASA the following September for astronaut training.

After a spell working in a support capacity for the last four Apollo lunar missions, he began actively pursuing the development of the shuttle and was heavily involved in the design of its cockpit displays and controls. At length, he was paired with astronaut Fred Haise for the ALT flights, then with Vance Brand for the fourth Orbital Flight Test (OFT) mission of Columbia, and finally, in the summer of 1979, with Jack Lousma for STS-3.

Fullerton flew as pilot of STS-3 in March 1982, an eight-day mission which successfully tested the shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm with real payloads and operated a battery of space science experiments. The mission ended dramatically when Edwards Air Force Base was left under several inches of rainwater and NASA was forced to divert Columbia to White Sands Missile Range, N.M., where Lousma touched down—and inadvertently performed what Fullerton described as “kind of a wheelie”—on the a runway of packed white gypsum.

Three years later, in July 1985, Fullerton flew his second mission, as commander of STS-51F. This eight-day mission, though ultimately successful, endured one of the most hair-raising pre-launch campaigns in shuttle history. An attempt to fly on 12 July was called off only seconds ahead of liftoff, when Challenger suffered the second Redundant Set Launch Sequencer (RSLS) abort in the shuttle era. Her three main engines were shut down after ignition, due to a last-moment glitch. Eventually, after repairs, Fullerton and his six crewmates thundered aloft on 29 July … only to suffer a main engine shutdown, 67 miles above Earth!

“The ground made the call ‘Limits to Inhibit,’ which is, for us, an extremely serious omen, [because it] means the ground is seeing problems that are going to shut you down,” recalled Story Musgrave, who served as Fullerton’s flight engineer for STS-51F. “I’m looking through the procedures book and thinking we’re going to land at our transoceanic abort site in Spain. I’m rehearsing all the steps and my hands are moving through the book and I’m thinking ‘We’re going to Spain. Things are bad!’”

The emergency, which occurred at T+5 minutes and 45 seconds, arose when temperature readings for the No. 1 main engine’s high-pressure turbopump indicated “above” its maximum redline, prompting Challenger’s computers to shut it down. At this stage of the ascent—with just three minutes remaining to a nominal Main Engine Cutoff (MECO)—the shuttle was already much too high and traveling much too fast to return to an emergency landing back at her launch site at the Kennedy Space Center, Fla.

This meant one of two things: either a Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) in Europe or a tricky maneuver known as an Abort To Orbit (ATO), whereby Challenger would burn her twin Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines to augment the two remaining main engines and limp into a low, but stable, orbit. Musgrave’s initial focus was upon the page of his checklist that dealt with requirements for a touchdown at Zaragoza Air Base—a joint-use military and civilian installation with a NATO-instrumented bombing range—in the autonomous region of Aragon, northeastern Spain. Zaragoza had been designated as a TAL site in 1983 and was assigned to 51F because the orbital inclination of 49.5 degrees placed it near the nominal ascent ground track, thus allowing the most efficient use of available main engine propellant and cross-range steering capability.

The TAL mode was the second available abort after the Return to Launch Site (RTLS) option and covered the six-minute period from shortly after Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) separation until, theoretically, MECO. Flight rules dictated that the TAL option would only be selected in the event of a premature main engine shutdown or other major malfunction—such as a significant cabin pressure leak or cooling system failure—which would prevent the vehicle from continuing into space and completing at least one orbit. Had the command been given from Mission Control that day, Fullerton would have rotated the abort switch on his instrument panel in the TAL/AOA position and depressed the abort push button next to the selector switch; Challenger’s computers would then have automatically steered the spacecraft toward the plane of the European landing site.

Eventually, the call came from Mission Control: “Abort ATO; Abort ATO.” Challenger had achieved sufficient velocity and altitude to undertake the next available option: the Abort to Orbit. In fact, she had missed the closure of the TAL “window” by just 33 seconds! At 4:06:06 p.m. EDT on 29 July 1985, some six minutes and six seconds into ascent and hurtling toward space at 9,000 mph, Fullerton fired the OMS engines for 106 seconds, but permitting the shuttle to continue into a lower-than-planned orbit. Two minutes later, at 4:08:13 p.m., the No. 3 main engine data indicated excessively high temperatures. If the “Limits to Inhibit” had not already been applied, the computer would have it shut down. The “inhibit” command effectively instructed the computers to ignore the over-temperature signals and prevented them from shutting down the No. 3 engine. The two remaining engines, meanwhile, fired for an additional 49 seconds, shutting down nine minutes and 20 seconds after launch.

Fullerton left the astronaut corps in 1986 and for several years worked as a research and test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base, flying a number of early missions to deploy the Pegasus air-launched rocket. I had the pleasure and the privilege to interview Fullerton over the telephone in 2004 and found him to be a warm, courteous man with a keenness to share his experiences of spaceflight and aviation. His passing on 21 August 2013, aged 76, leaves an enormous gulf as the human race has lost yet another of its pioneering space sons.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

A fitting tribute to a true pioneer in the US manned space program.

GREAT JOB BEN & AMERICASPACE!! Lived thru these times….but most Americans were so busy living THEIR lives that we never knew even one-tenth the drama of what REALLY HAPPENED……”up there”. Has been a great pleasure & genuine education RELIVING it in DETAIL from outlets like AmericaSpace & writers like Ben Evans & quite literally ‘brought into focus’ by some of the greatest photographers that ever were!!!

Mary: AmericaSpace is providing its readers with outstanding historical articles that supplement the numerous books written on spaceflight. For those of us who have lived through the Space Age since Sputnik, the writers provide rich detail and insight into the “historical record.” Their work will ultimately enrich the knowledge base of the most significant technological achievements of mankind.

Tom and Mary: Thank you for your exceptionally well-written posts. Your eloquence also highlights the fact that the excellent quality of material provided by AmericaSpace and writers such as “The Master” Ben Evans draws individuals to this site whose intelligent, well-reasoned, respectful posts are a pleasure to read. Tom is exactly correct (no surprise there) in pointing out that AmericaSpace provides outstanding articles and invaluable information to be found nowhere else. This exemplary work by Ben Evans featuring the incredible life of Gordon Fullerton, filled with outstanding achievements, is a case directly on point. The mainstream media fails miserably in informing the general public about our true heroes, such as Gordon Fullerton, but dutifully keeps us up to date every time Justin Bieber drives too fast through his subdivision. I grieve the loss of this great man. Seeing him sit on the Shuttle flight deck next to Jack Lousma (whom I had the great pleasure of speaking with at length) brings home the fact that although AmericaSpace and writers like Ben are performing a priceless public service in preserving the “national treasure” that resides in the experiences of these heroic individuals, they cannot do it all. Please Public Broadcasting, please Ken Burns, the history of spaceflight is screaming for a series featuring the exciting, electrifying, momentous events that forever changed humanity. The precious, priceless recollections of the pioneers of human spaceflight such as Gordon Fullerton cannot be allowed to slip through our fingers like grains of sand.