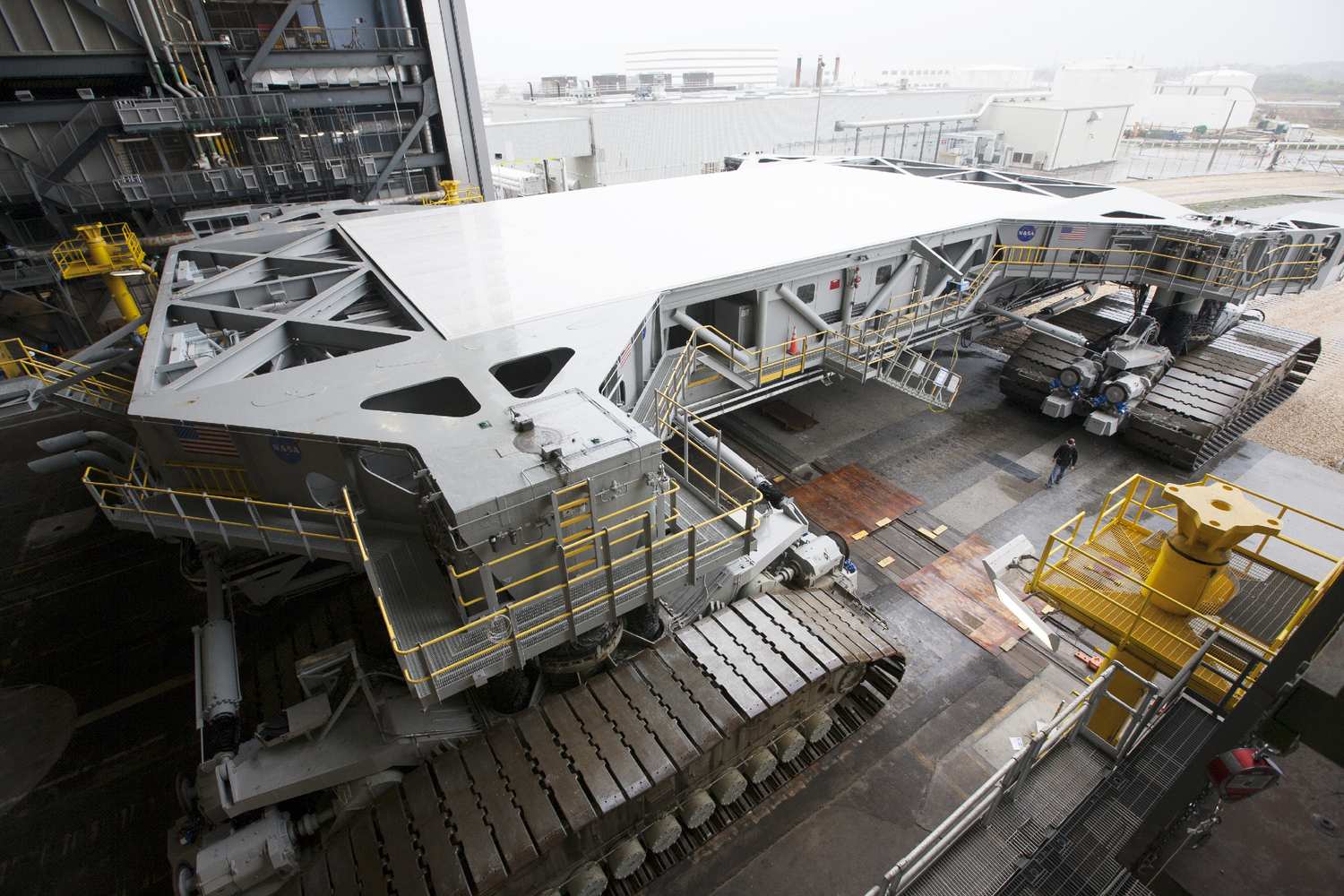

It will be several years before NASA’s two giant crawler-transporters are put to use again, but work at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida has been underway for some time to make them ready for NASA’s next generation of human-spaceflight vehicles—the Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion spacecraft—and recently the work done on crawler-transporter 2 (CT-2) passed the first phase of an important milestone test in the behemoth vehicle’s upgrading development.

The test, carried out by the Ground Systems Development and Operations Program, put the new traction roller bearings on CT-2 to work on two of the massive vehicle’s truck sections, A and C, for a drive outside of the iconic Vehicle Assembly Building last month. Both left- and right-hand steering was tested as the mammoth 5.5-million-pound beast moved along crawlerway C (between the Vehicle Assembly Building and Ordnance Road for those familiar with the area). Visual inspections of the roller bearing pumps, valves, and lines were also conducted to make sure the new roller assemblies received the required flow of grease from the grease injectors, and the temperature of the roller assemblies was measured with handheld infrared temperature monitoring devices.

“The temperature of the roller assemblies were monitored and recorded using newly-installed thermocouples,” said Mike Forte, a senior project manager with QinetiQ on the Engineering Services Contract. “We were looking for any anomalies and establishing a baseline operating temperature for the new roller assemblies. We also closely monitored the system for any unanticipated vibrations or noise, which are indications of problems.”

NASA has two crawlers, but in order to support a 21st century spaceport the agency is upgrading each for different tasks. One of the crawlers will be dedicated to NASA’s SLS / Orion human spaceflight program, while the other crawler will be upgraded for moving various types of rockets and spacecraft, such as SpaceX Falcons and Dragons (SpaceX is currently negotiating a lease agreement with NASA to use former shuttle Launch Complex 39A).

Both CT-1 and CT-2 have served NASA well for over 40 years, traveling the freeway-wide gravel track between the VAB and Launch Complex 39 with skyscraper-size, Moon-bound Saturn V rockets and space shuttles. They remain the largest self-propelled land vehicles in the world, but that’s not currently good enough to move the SLS. With the space shuttles the crawler moved a total of 12 million pounds three to four miles to launch pads 39A or 39B, a slow-motion (but very impressive) drive which took around six hours from start to finish. The whole SLS / Crawler vehicle (the rocket, spacecraft, mobile launch platform, and crawler itself) will weigh some 18 million pounds when rolled out to the pad in a few years, which is 6 million pounds more than the crawler’s current lifting capacity.

“The crawler is like a locomotive. It’s diesel-electric — there’s two diesel engines, which produce DC current — which is what makes us move,” explained crawler manager Ray Trapp in 2010. “The steering and the jacking and elevation of the crawler, the chassis and the mobile launcher, it’s all done by hydraulics. All of that basically is drive-by-wire, so there’s a steering wheel in the cab. You have to plan ahead, because obviously it doesn’t turn on a dime, you have to really be on your game and be thinking ahead about where you want to be, one, two, three minutes ahead of time.”

The three-story-tall, 31-foot-long, 113-foot-wide crawler, which was originally built by the Marion Power Shovel Company at a cost of $14 million ($100 million today), can move along at a blazing speed of 2 mph—without a rocket sitting on its back. With the 6-million-pound shuttle stack the crawler moved along at 0.8 mph. Such blazing speeds obviously require lots of fuel, and the crawler can carry along 5,000 gallons of it at a time. Its gas mileage, however, is not its best selling point, as the crawler only gets 42 feet per gallon, or 125.7 gallons per mile, while moving along on 456 tred-belt shoes. Incredibly, each shoe is 7.5 feet long by 1.5 feet wide, and each shoe weighs one ton.

In addition to the 88 new traction roller bearing assemblies, CT-2 also now has a modified lubrication delivery system and a new temperature monitoring system that includes 352 new thermocouples. The crawler’s control rooms and cabins have new touch screen displays, and both engine rooms—each with two engines—are being modernized to support the new responsibilities that lie ahead. Each vehicle also has new AC generators, and their DC generators are being upgraded.

Now back in the VAB, CT-2 is currently receiving more new roller bearing assemblies on the B and D truck sections, with the second test scheduled to take place next November after installation of the second set of bearings is completed. Future tests, according to Forte, will be used to establish permanent operational warning and shutdown limits for a fully-loaded crawler-transporter.

“A couple of us were sitting around about quarter to midnight or so, and an e-mail came in from our launch director, Mike Leinbach, and he said, ‘You guys have got to come out here and see this.’ And we ended up staying for hours, because it is absolutely incredible to see.” — Ken Ham, STS-132 Commander

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

BELOW: Photos of some recent work to CT-2, including its test drive last month. Photos courtesy of NASA.