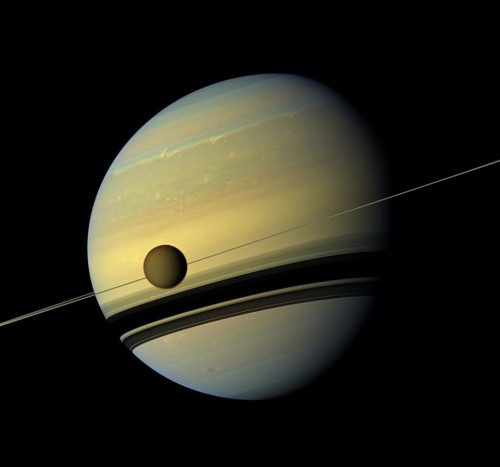

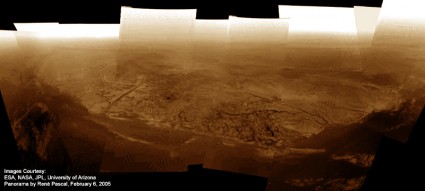

Ever since the Voyagers beheld its strange, orange-hued veil of hydrocarbon smog, more than three decades ago, Titan has exerted a tantalizing pull on the human psyche. The largest moon of Saturn—and the second-largest-known natural satellite in the Solar System—was thought to closely resemble what Earth may have been like billions of years ago, long before life evolved. For the past decade, the Cassini spacecraft has explored Titan, and in January 2005 its Huygens probe plunged into the moon’s atmosphere and soft-landed on its surface. Our knowledge of this strange world continues to expand exponentially, but now laboratory investigators at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., have drawn intriguing conclusions from Earth-based simulations of the peculiar Titanian atmosphere.

Published this week in Nature Communications, the results of the work indicate that complex organic chemistry—possibly providing the building blocks of life—may extend substantially lower in Titan’s gaseous envelope than was previously thought. “Scientists previously thought that as we got closer to the surface of Titan, the moon’s atmospheric chemistry was basically inert and dull,” said Murthy Gudipati of JPL, the paper’s lead author. “Our experiment shows that’s not true. The same kind of light that drives biological chemistry on Earth’s surface could also drive chemistry on Titan, even though Titan receives far less light from the Sun and is much colder. Titan is not a sleeping giant in the lower atmosphere, but at least half awake in its chemical activity.”

Titan’s thick atmosphere is known to be home to hydrocarbons, including methane and ethane, which can develop into smog-like airborne molecules with carbon-nitrogen-hydrogen bonds, known as “tholins.” “We’ve known that Titan’s upper atmosphere is hospitable to the formation of complex organic molecules,” said co-author Mark Allen, principal investigator of the JPL Titan team that is a part of the NASA Astrobiology Institute, headquartered at Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif. “Now we know that sunlight in the Titan lower atmosphere can kickstart more complex organic chemistry in liquids and solids rather than just in gases.”

The team examined an ice form of “dicyanoacetylene,” a molecule detected on Titan and related to a compound that turned brown after being exposed to ambient light in Allen’s lab 40 years ago. In this latest experiment, dicyanoacetylene was exposed to laser light at wavelengths as long as 355 nanometers. Light of that wavelength can filter down to Titan’s lower atmosphere at a modest intensity, akin to amount of light that comes through protective glasses when Earthlings view a solar eclipse, Gudipati said. The result was the formation of a brownish haze between the two panes of glass containing the experiment, confirming that organic-ice photochemistry at conditions like Titan’s lower atmosphere could produce tholins.

The complex organics could coat the “rocks” of water ice at Titan’s surface, and they could possibly seep through the crust to a liquid water layer under Titan’s surface. In previous laboratory experiments, tholins like these were exposed to liquid water over time and developed into biologically significant molecules, such as amino acids and the nucleotide bases that form RNA. “These results suggest that the volume of Titan’s atmosphere involved in the production of more complex organic chemicals is much larger than previously believed,” said Edward Goolish, acting director of NASA’s Astrobiology Institute. “This new information makes Titan an even more interesting environment for astrobiological study.”

All the more reason for a full-fledged “scientific assault” on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. I’ve always maintained that the building blocks of life, if not basic forms of life itself, reside in our “backyard.” The technical challenges are daunting but we have proven what can be accomplished. As a species, we would be remiss not to thoroughly investigate our backyard neighbors!