In the latter half of 2014 NASA plans to launch the first of its Orion spacecraft and to begin testing the RS-25 engines which will be used on the space agency’s new heavy-lift booster, the Space Launch System, or “SLS.” Testing of these engines will take place at NASA’s Stennis Space Center located in Mississippi.

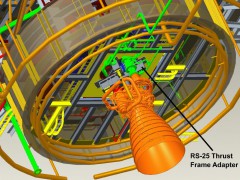

Stennis’ A-1 Test Stand is having a nearly 8,000-pound thrust frame adapter built so that the stand will be able to test the RS-25 rocket engine. The RS-25 will be used to provide core-stage power for SLS. The thrust frame adapter is slated to be built and installed by November 2013. Then the real fun begins.

“We initially thought we would have to go offsite to have the equipment built,” said RS-25 Test Project Manager Gary Benton. “However, the Stennis design team figured out a way to build it here with resulting cost and schedule savings. It’s a big project and a critical one to ensure we obtain accurate data during engine testing.”

As it currently stands, there is no modular test stand; as such, each engine needs a stand designed to that engine’s specific requirements. The adapter currently under construction will be attached to what is known as the Thrust Measurement System. Then an RS-25 will be attached to the adapter. The adapter then gets put through its paces.

The adapter has to not only hold the engine in place, but also absorb the furious power unleashed when the RS-25 is activated. The adapter must hold the engine steady enough for accurate measurements of how the engine is performing.

As it currently stands, the A-1 Test Stand is set up to hold and test the J-2X rocket engine and is not ready to handle the RS-25. The RS-25 produces nearly twice the amount of thrust as the J-2X (the J-2X produces 294,000 pounds of thrust, while the RS-25 produces 530,000 pounds of thrust).

NASA has partnered with Lockheed-Martin’s Test Operations Contract Group to design the adapter. As with any NASA initiative, while the space agency and the primary contractor work to ensure the adapter meets the requirements, sub-contractors are also heavily involved. In this case, Jacobs Technology provided welders and machine shop teams who labored to guarantee the test stand was up to the challenge. This is no simple task.

“It’s a challenging project,” said Jacob Technology’s RS-25 Project Manager Kent Morris. “It’s similar to the J-2X adapter project, but larger. It will take considerable man hours to perform the welding and machining needed on the material. The material used for the engine mounting block alone is 32 inches in diameter and 20 inches thick.”

Engineers have to consider a variety of factors. These include stresses on the test frame and ensuring that the engine “gimbals” (rotates during firing), as well as the strengths and potential weaknesses of the components and materials being tested.

“This is a very specific process,” Benton said. “It is critical that thrust data not be skewed or compromised during a test, so the adapter has to be precisely designed and constructed.”

Building the adapter is a rather involved process; the material of which it is comprised must be handled and shaped. The engineers working on the structure must have special training, and the design and materials used must be capable of handling extreme stresses and temperatures.

According to a release issued by NASA, the adapter is physically the largest facility item required to test the RS-25. The adapter, however, is just a single component in a far larger machine which is needed to adequately put the RS-25 to the ultimate test.

The process to modify the A-1 Test Stand is part of a highly choreographed ballet which should see the J-2X components phased out of the A-1 stand, and the RS-25 components installed, at the end of this summer.

Tests should specifically focus on how the RS-25 will work on SLS, as these engines have a track record that extends back more than three decades. The RS-25 is better known as the Space Shuttle Main Engine, or “SSME.” The RS-25 is a liquid-fuel cryogenic engine built by Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne. It burns cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. Each RS-25 is capable of producing nearly 420,000 pounds of thrust at liftoff. Three of these engines were used on each of NASA’s space shuttles.

Like shuttle, the RS-25s, along with two boosters, will provide the necessary thrust during the first stage of the mission. Unlike shuttle, they will be lost after staging.

The first unmanned test flight of the SLS is currently scheduled to occur no earlier than 2017. NASA plans to fly astronauts using the heavy-lift booster sometime between 2021 and 2022.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace