Since the beginning of the space shuttle era, which kicked off with STS-1’s triumphant launch in 1981, space buffs, historians, and writers chronicling the stories of spaceflight have heard tales from the astronauts who made that era ubiquitous in the form of biographies and oral histories. Many of these astronauts, while not household names, are icons in the space community—one thinks of Young, Crippen, Musgrave, and Ride, for example. However, the successes of the shuttle era were also made possible by the thousands of workers who helped process orbiters and their “stacks” during the program’s 30-plus years, and while they may not be as well-recognized, they, too, have stories to share encompassing a rich history.

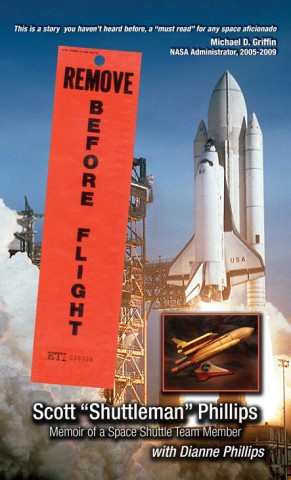

One of those workers, Scott G. Phillips, is now telling his story in his newly-released book, Remove Before Flight (Tate Publishing, co-written with his wife, Dianne Phillips). In addition, Phillips also memorializes the space shuttle and its legacy through his one-of-a-kind handcrafted wooden shuttle models, many of which have been presented to the crews who have occupied the orbiters.

Phillips’ desire to be part of America’s human spaceflight program started during his childhood, when he watched a fellow Ohioan—Neil A. Armstrong—take his first iconic steps upon the lunar surface. Phillips wrote in his book: “I felt a swell of emotion begin to overtake me. I, too, wanted to be a part of something important, something larger than myself. I imagined space as my own frontier.” His fate was sealed. Already armed with a passion for woodworking, his dream of working in the space program was realized after interviewing with Martin Marietta in his late teens. He wrote:

“The next day, October 20, 1978, I became known as Badge #89581. I was hired as a mechanical technician to perform a variety of tasks, including laying strain gauges, running electrical wires, building enclosures, and torquing bolts on the liquid oxygen portion of the External Tank located in the high bay. It didn’t seem to matter to them that I knew nothing about strain gauges. In fact, I didn’t even know what a strain gauge was. But I was willing to work twelve-hour days, seven days a week. I guess they figured I’d quickly learn or burn out trying.”

He added: “The entire Space Shuttle Program seemed surreal. I had no idea what I was embarking on, but I knew it was something big.” Within a few years, Phillips would learn his job quickly, eventually becoming the last technician out of the white-painted ET-1 tank flown on STS-1. He still has the “Remove Before Flight” tag attached to the tank, which would become the title of his memoir. Phillips worked at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., for 33 years, from the nascent beginnings to the bittersweet end of the program.

His favorite orbiter was Columbia because it represented some of his favorite missions (STS-1, STS-62, STS-93, and STS-109)—although from a sad perspective, it also represented STS-107. He considers his most memorable mission STS-1, partly for his status being the last technician out of the ET. He added: “It was the first launch I attended and very historic. It also motivated me to build my space shuttle models I’m known for today.”

His time working on the shuttle was not without tragedy, as the program experienced two crew losses with STS-51L (Challenger, January 1986) and STS-107 (Columbia, January 2003). Like many space workers, Phillips appreciated how difficult (and risky) the business of putting humans into space could be: “I had the NASA photo lab enlarge a photograph of the Challenger crew to 16- by 20-inches. It hung on my office wall for the rest of my career, serving as a constant reminder of how unforgiving human space flight can be.”

During his time working in the program, he was also able to join his two passions—the space shuttle and woodworking—by making tribute models depicting the orbiters. Realizing that each mission carried historic weight, Phillips set forth to preserve each flight through his woodwork. “The Shuttle Program represented the pinnacle of the aerospace community, and I wanted my models to reflect that excellence. I was bursting with enthusiasm to document for future generations how these brave men and women pushed the envelope of human understanding, the beginning of life in space,” he enthused in his book.

Despite the end of the shuttle program in 2011, Phillips is still keeping its spirit alive through his models and his book. In addition, he has some words of wisdom to the younger generations of space workers who will make commercial crew to low Earth orbit and Orion/SLS happen.

In an interview, he stated: “To the next generation, I would say that it is important to attach yourself to something larger than yourself. Be prepared with the best education you can, a strong work ethic, and good social skills. Find your passion and work it into your profession. Weather the hard times (personal, job setbacks or major program changes) and learn from them. If you’re open to it and find unconditional love, it will give you the support and wisdom to carry you the distance of your life. Then, invest in yourself during your career.”

As we enter a new generation of space vehicles including Orion, meant for deep space and Mars, Phillips remains excited about the future. He looks forward to a time when humankind visits our planetary neighbor. “Mars is the logical next step for mankind. A mission to Mars for the next five generations is required to make us a multi-planet species,” he stressed.

Would Phillips do it all over again, despite the considerable stresses of working in a career fraught with risks? He answered unhesitatingly: “Yes, I would absolutely do it again! This is where having a passion for something larger than yourself becomes valuable. When you lose something or someone, your passion carries and insulates you to get through and move beyond the hard times. Without having something to anchor you, you can temporarily lose your way. When we grieve, it’s not for the person or the situation that changed. Rather, I believe we selfishly grieve for ourselves. I found that the sooner I returned to my passion, the better able I was to forge ahead with my work and goals. And, never be afraid of failure; it is your best teacher.”

Phillips and workers like him are why the U.S. human spaceflight program has continued to move forward despite encountering adversity. In his words, “Shuttleman” added: “I learned these things working with hundreds of highly skilled and motivated people in our beloved Space Shuttle Program. I want the next generation to build off the shoulders of giants!” With mentors such as Phillips who carry on the legacies of previous programs, a newer generation of space workers has plenty of inspiration from which to draw.

Remove Before Flight is available through http://removebeforeflightbook.com. Information about Phillips’ shuttle models is also available through the website.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace