Almost two decades ago, America’s shuttle program began living up to its billing as a vehicle for delivering experiments, equipment, and supplies to an Earth-circling space station. And in the small hours of 12 January 1997, Atlantis roared aloft on a mission to exchange long-duration U.S. astronauts aboard Russia’s Mir orbital outpost and to transport upwards of 6,100 pounds (2,800 kg) of logistics in a pressurized Spacehab double module. During STS-81, astronaut Jerry Linenger was dropped off at Mir and John Blaha returned to Earth in his stead, whilst the “core” shuttle crew of Commander Mike Baker, Pilot Brent Jett, and Mission Specialists Jeff Wisoff, John Grunsfeld, and Marsha Ivins and the station’s own crew of Russian cosmonauts Valeri Korzun and Aleksandr Kaleri supported one of the most complex and ambitious joint flights ever attempted.

In fact, Blaha had spent a considerable period since Christmas 1996 preparing for his departure, by packing 15 bags with equipment to bring back to Earth. An additional illustration of the closeness of the U.S.-Russian partnership came on 10 January, when one of two cooling fans in a freezer for the myriad biological experiments failed. Although Blaha was able to remove the freezer door, attach a replacement, and effect a temporary repair—thereby keeping temperatures as cool as possible in the interim—he spoke to Flight Surgeon Pat McGinnis and engineer Matt Mueller on the ground, who managed to locate replacement fans and have them delivered to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) and loaded aboard Atlantis, as the shuttle sat vertically on the launch pad.

Overall, STS-81 would bring 1,400 pounds (635 kg) of water, 1,140 pounds (516 kg) of U.S. research gear, 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg) of Russian equipment, and 265 pounds (120 kg) of “miscellaneous” materials to Mir, as well as ferrying almost 2,425 pounds (1,100 kg) of unneeded items back to the Home Planet. Among the items to be brought home by Atlantis’ crew were wheat samples from Mir’s Svet greenhouse—which would mark the first occasion in history that plants had completed a full growth cycle in space—whilst STS-81 would also deliver the Treadmill Vibration Isolation and Stabilization System (TVIS) for testing and evaluation in readiness for its role aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

In his 2000 memoir, Off the Planet, Jerry Linenger reflected upon the often wry sense of humor of John Grunsfeld, who was recently interviewed by AmericaSpace’s Ken Kremer in a pair of articles: here and here. As an undergraduate, Grunsfeld had worked on his car in a self-help garage run by two Masschusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) graduates, who later started a popular radio program, called “Car Talk.” Prior to the STS-81 launch, Grunsfeld arranged with the producers to play a prank on the show’s hosts. Whilst in orbit, his telephone was patched through to the unsuspecting hosts.

Without identifying himself, Grunsfeld complained about his U.S. Government-issued vehicle, with its horrendous gas mileage and its habit of running extremely roughly for the first two minutes of operation, with lots of shaking. However, he added that after two minutes, it performed like a champ … at least, that is, until it reached eight minutes, when its engine died completely. The hosts were mystified. Did the vehicle achieve good acceleration, they asked?

“Oh, yeah,” replied Grunsfeld. “About 17,500 miles an hour!”

The hosts realized they had been had. “Who is this?” they asked.

Only then did Grunsfeld identify himself as an astronaut aboard Shuttle Atlantis.

Originally scheduled for launch on 5 December 1996, a series of troubles with the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) throughout the summer pushed each of the shuttle-Mir flights back by approximately six weeks, with STS-79 moving from late July until mid-September and STS-81 correspondingly shifting to 12 January 1997. Atlantis’ processing flow ran very smoothly, punctuated only by the need to replace a fuel cell, which had exhibited high pH levels, and the STS-81 crew and Linenger arrived at KSC on 8 January, ahead of the formal start of the 43-hour countdown. Launch on the 12th took place at 4:27:23 a.m. EST, at the opening of a short, 10-minute “window,” and by the time the shuttle achieved orbit Mir was travelling over the Galapagos Islands, about 2,765 miles (4,450 km) to the southwest. About 25 minutes after liftoff, the Mir incumbent crew of Korzun, Kaleri, and Blaha were notified and watched a video uplink from Mission Control.

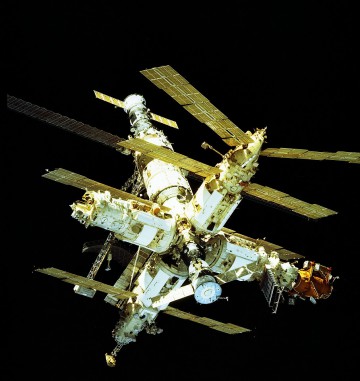

Embarking on a well-trodden, two-day rendezvous profile, Atlantis’ crew set to work establishing laptops and laser ranging equipment and opening up the Spacehab double module in the payload bay. Wisoff, Grunsfeld, and Linenger worked on the assembly of the TVIS and tested its restraint system, motor, running surface stability, and effectiveness in reducing disturbances to the surrounding microgravity environment. Meanwhile, Ivins activated the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Biorack facility and Jett and Grunsfeld installed the centreline camera into the Orbiter Docking System (ODS), ahead of docking. On 14 January, Mike Baker greeted Mission Control’s wake-up call with a chirpy “Good morning, Houston, 500 miles to go!” Following the R-Bar rendezvous profile—and heading directly “up” from the center of Earth toward Mir—Baker performed a successful docking at the Docking Module (DM) on the space station’s Kristall module at 10:55 p.m. EST.

The STS-81 crew had actually sighted Mir from a distance of about 40 miles (64 km), but from the station John Blaha did not spot Atlantis until just eight minutes or so before physical docking. Grunsfeld and Linenger then set to work on the process of equalizing pressure between the two spacecraft, ahead of opening the hatches. Through the porthole, inside Kristall, Linenger could see a jubilant Blaha and Korzun. As the hatches opened, in Linenger’s recollection, the shuttle crew was greeted by “an uninhibited laugh” from Blaha. “Then bedlam erupted,” he continued, “as the six of us blundered our way through the hatch and bumped heads with the much more graceful (being fully adapted to space) threesome of Mir occupants. The scene was one of hugs, shouts, mixed language and laughter, feet dangling in all directions. Nine spacefarers embracing and floating in every which way. After the chaos calmed, we all migrated, single file, heads closely following feet, into Mir.” In a similar manner to previous flights, after the welcoming ceremony, Blaha and Linenger swapped their molded Soyuz-TM seat liners and rejoining their respective crews.

The shuttle crew gave Korzun and Kaleri new flashlights, because sections of Mir were being kept dark in order to converse electricity. (In fact, a master alarm sounded with a low-power warning, midway through the welcoming ceremony, much to Korzun’s embarrassment.) It was a clear indication that, although “The Partnership” between the United States and Russia in shuttle-Mir was now in full flow, there remained many issues to overcome … and 1997 would prove one of the most hazardous and testing years endured by the joint relationship in its troubled, yet ultimately triumphant effort to develop the ISS.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Love the “Car Talk’ story!

Just superior writeup. The idea actually would have been a entertainment account them. Glimpse leading-edge in order to a lot more introduced pleasant within you! However, exactly how should we be in contact?