More than five years have now passed since Dottie Metcalf-Lindenburger—geologist, astronomer, cross-country runner, and the first Space Camp alumnus ever to journey beyond Earth’s atmosphere and into orbit—became NASA’s fourth Educator Astronaut and launched aboard Shuttle Discovery on STS-131 to the International Space Station (ISS). Metcalf-Lindenburger, who turns 40 today (Saturday, 2 May), grew up with parents, grandparents, and an aunt in the teaching profession. Years later, and by now a teacher herself, one of her students started her on the path to someday become an astronaut. Her story is the story of the power of education and learning. “Education can take you anywhere,” Metcalf-Lindenburger told a NASA interviewer. “Life is a journey, but education takes you along the way. And it can take you down many roads.”

Dorothy Marie Metcalf was born in Colorado Springs, Colo., on 2 May 1975, the daughter of science teacher Keith Metcalf and mathematics teacher Joyce Metcalf, “so no big surprise that I love math and science.” As a child, the family moved to Loveland, where she received her elementary education, and finally settled in Fort Collins for junior high and high school. “I just think growing up along the Front Range provides you with a lot of opportunities,” she told a NASA interviewer, years later. “First of all, you take topography for granted, until you move to a place like Houston, and you don’t have mountains. It’s like every day is pretty sunny in Colorado, so you’re used to looking at the sky, and at night the sky is gorgeous. I knew several constellations growing up, just because it’s easy to pick them out, and fossils were really abundant in my backyard.”

It was perhaps for this reason that she found herself drawn to geology and astronomy and, with her younger sister, frequently spent time digging fossils. “I didn’t know until later, when I became a geologist, just how lucky I was, because when you’re in geology, it’s pretty hard to actually find fossils often and you may spend a lot of time digging before you get one.” With parents, an aunt, and both of her grandmothers who were both teachers, it is little surprise that education proved a cornerstone to her life. In time, she and her sister and their cousin would also become teachers.

After high school, she entered Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash.—“a small liberal arts school in the middle of pretty much nowhere”—initially to study mathematics, following in her mother’s footsteps, but ended up taking a geology course during her freshman year and enjoyed it so much that she pursued it as her major. During the course of her undergraduate career, she worked near Yellowstone, mapping the last glaciation of Russell Creek in Wyoming, and completed her senior thesis outside Canyon City, Colo., determining the petrology of 2.5-billion-year-old rocks in the Wet Mountains. “Both of those,” she said later, “were real different research projects.”

Upon receipt of her degree in 1997—and having also received Whitman College’s Dr. Albert Ripley Leeds Memorial Prize in Geology, in recognition of her “outstanding potential in the geological sciences”—she had decided to pursue a career in education and was accepted into the Peace Corps, with the intent of traveling to Kazakhstan to teach English. However, it was not to be. “That was right when there were just some upheavals in that part of the world,” she said, “and they didn’t let me do Peace Corps there.” Instead, she remained in the United States and gained a teaching certification from Central Washington University in 1999, specializing in science and history. Qualifying as a teacher, she was further honored as the Outstanding Teacher Preparation Candidate of the year.

Her first teaching appointment was at Hudson’s Bay High School in Vancouver, Wash., where she taught Earth science and astronomy for five years and coached cross-country running and Science Olympiad. It was a post she continued to hold through her acceptance by NASA as an astronaut candidate in May 2004, by which time she had married fellow teacher Jason Lindenburger.

Space exploration had long grasped her imagination, ever since the Voyager missions opened up the outer Solar System and revealed four distant planets as worlds, rather than points of light. “The first time that I thought I could even be an astronaut was when I was in about eighth grade,” she recalled. “I did a writing competition, at that time through Martin Marietta, and I took second place.” In doing so, she missed out on the first-place prize of a trip to Space Camp, but her parents sent her to the Huntsville, Ala.-based camp the next year, and the experience was a profound one. When she was selected by NASA, Metcalf-Lindenburger became the first Space Camp alumnus to be chosen as an astronaut and, in 2007, was inducted into its Hall of Fame.

“It was there that I realized if I keep working hard in math and science, it’s a possibility that I could work at NASA,” she remembered of her time at Space Camp. “I kind of saw behind the scenes of what different people would do during a mission; not just what astronauts do, but what the ground does as well.” It was many years later, however, whilst teaching at Hudson’s Bay High School, in the spring of 2003, that one of her students asked the age-old question: How do you go to the bathroom in space? Metcalf-Lindenburger did not know, but promised to find out. That evening, she visited NASA’s website and what she saw would change her life forever.

The agency had long courted the teaching profession, ever since the ill-fated Teacher in Space Project (TISP) which saw the selection of future 51L crew member Christa McAuliffe and her backup, Barbara Morgan, in July 1985. After the loss of Challenger and the tragic deaths of McAuliffe and her crewmates in January 1986, the idea of someday flying a teacher remained a key goal for NASA, but the decision was delayed through the early 1990s, partly due to “the continuing backlog of high-priority missions on the shuttle manifest.” Shortly before handing the leadership of NASA to his successor, Dan Goldin, in March 1992, outgoing Administrator Dick Truly recommended that Morgan should fly aboard a future shuttle mission. Under Goldin’s leadership, Morgan was selected as the first Educator Mission Specialist in January 1998 and began formal training with the 17th class of astronaut candidates in June of that year. After a long period of training, she was finally assigned in December 2002 to shuttle mission STS-118, the next orbital voyage of Columbia after the STS-107 research flight.

With the loss of Columbia in February 2003, shuttle operations were placed on hiatus for more than two years, but it was during this dark time that NASA’s Educator Astronaut Program (EAP) sought to recruit new teachers to join the agency. The program was announced in January, whilst the STS-107 crew was in orbit, and by mid-March more than 6,200 teachers nationwide had tendered their applications. The aim of the project was for a cadre of educator astronauts “to provide a direct connection between America’s teachers and students,” as part of a renewed commitment “to get students excited about science, technology, engineering and mathematics.” Shortly thereafter, NASA announced that the closing date for Educator Astronaut applications was 30 April 2003.

As she investigated NASA’s website for her student, Metcalf-Lindenburger spotted the announcement and submitted an application. “I had the answer to my student’s question,” she said later, “but I also got an answer to a dream that I had for a long time.” By her own admission, she forgot about her application as the year wore on, but was surprised in the summer to return from a hiking expedition in Arizona to receive a letter from NASA, inviting her to proceed. The following November, she arrived at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, for a week of interviews and tests, still under the impression that the visit would be the closest she would come to becoming an astronaut.

She was wrong.

Metcalf-Lindenburger was selected by NASA as one of three Educator Astronauts—alongside a pair of mathematics and science teachers, Joe Acaba and Ricky Arnold—in May 2004 and underwent intensive training in shuttle and International Space Station (ISS) systems as part of the Group 19 intake, whose number also included future Deputy Chief Astronaut Chris Cassidy. Less than two years later, in February 2006, she and her colleagues received their silver astronaut pins in a private ceremony at JSC. Soon afterwards, she entered the Astronaut Office’s Station Branch, leading work on systems and crew interfaces. Specifically, she worked with fellow astronaut Clay Anderson on transitioning the computers aboard the ISS to an Ethernet network.

Almost three more years passed before Metcalf-Lindenburger received her first flight assignment in December 2008, announced as a Mission Specialist on STS-131, the penultimate voyage of Shuttle Discovery. She remembered being at her desk, when she received a call to go down to the front office to see Chief Astronaut Steve Lindsey. “He pulled me into his office,” she recalled, “and said “Congratulations! I think you would be a good member of STS-131.” By her own admission, the news did not sink in at first, but she finally called her parents, but swore them to secrecy until NASA made its formal crew announcement. Originally scheduled for launch in February 2010, the crew also included Commander Alan Poindexter, Pilot Jim Dutton, and Mission Specialists Rick Mastracchio, Clay Anderson, Stephanie Wilson, and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) astronaut Naoko Yamazaki, and were tasked with executing three EVAs, extensive robotic activities, and delivering payloads and supplies aboard the Leonardo Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM).

After several delays, the 15-day mission got underway on 5 April 2010, and Metcalf-Lindenburger’s core responsibilities including serving as flight engineer during ascent and re-entry, assisting with the inspection of the shuttle’s wing leading edges and other surfaces with the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS), and providing intravehicular support and Remote Manipulator System (RMS) operations during the EVAs by Mastracchio and Anderson. Arriving at the ISS, the astronauts were greeted by the incumbent Expedition 23 crew of Commander Oleg Kotov of Russia, U.S. astronauts Timothy “T.J.” Creamer and Tracy Caldwell-Dyson, JAXA’s Soichi Noguchi, and Russian cosmonauts Aleksandr Skvortsov and Mikhail Kornienko. It marked the first occasion that as many as four women were aboard a single spacecraft at the same time, as well as the first time that two Japanese astronauts had been in space together.

During the course of the mission, she spoke to eighth-grade students during a link-up with the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., and also to children at Eastern Guilford High School in Gibsonville, N.C., which was hosting elementary and middle school pupils. Also ferried into orbit aboard Discovery were mementoes from each of the crew members, including a black and gold pennant from Hudson’s Bay High School and a “Peace Pole” from Bennett Elementary in Metcalf-Lindenburger’s hometown of Fort Collins, Colo. In flying aboard Discovery for the penultimate time, Metcalf-Lindenburger and her fellow STS-131 rookies, Dutton and Yamazaki, became the final group of first-time astronauts ever to fly aboard the shuttle. When the orbiter touched down on 20 April 2010, after 15 days, 2 hours, and 47 minutes, and 238 orbits of Earth, STS-131 established itself as the longest mission ever undertaken by Discovery.

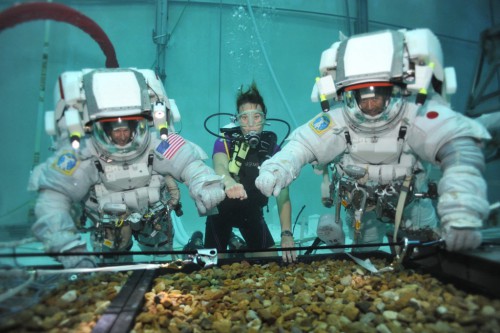

Following her mission, Metcalf-Lindenburger worked as a Cape Crusader, supporting the final three shuttle missions, before her next assignment in April 2012 to command the 16th expedition of the NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations (NEEMO) undersea research facility. Situated 63 feet (19 meters) below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Reef Base habitat, off the coast of Key Largo, Fla., the facility would support Metcalf-Lindenburger and her NEEMO-16 crewmates—JAXA astronaut Kimiya Yui, Cornell University planetary scientist Steve Squyres and European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Tim Peake—for 12 days from 11 June 2012 as they worked to test innovative solutions to engineering challenges, allowing astronauts to eventually explore asteroids. “As if the prospect of living for 12 days underwater wasn’t exciting enough, it gets better,” exulted Peake in an ESA blog. “The aim of NEEMO-16 is to simulate a future mission to an asteroid. This is the current focus for NASA’s first manned mission into deep space, venturing beyond the Moon’s orbit and once more pushing the boundary of human presence in our Solar System.”

Two years later, in June 2014, Metcalf-Lindenburger announced her departure from NASA, a little more than a full decade since being selected into the astronaut corps. “Dottie has been a tremendous asset to our office,” said Chief Astronaut Bob Behnken. “As an educator, her enthusiasm for sharing the excitement of space exploration was infectious and she was a great influence on our office and our work to inspire the public. She brought that same passion and dedication to her work as an astronaut. She will be missed, but we know she will continue to share the spirit of exploration wherever her path leads her next.”

In retrospect, it is perhaps fitting that Metcalf-Lindenburger was one of the last to fly aboard the shuttle and, equally, that she did not remain with NASA to fly one of the next generation of piloted space vehicles. “Shuttle has been my life since I was growing up,” she said, shortly before launching. “It’s the only vehicle I know.” Just prior to STS-131, her mother happened to be cleaning out her childhood bedroom and came across a model shuttle from Space Camp.

Metcalf-Lindenburger laughed. “You probably need to take down the shrine!”

Her mother paused for a moment, looked at the model, then replied with astonishment: “It’s Discovery!”

And it was. The shuttle model that a 14-year-old girl had made at Space Camp, almost exactly 20 years earlier, propitiously bore the name of the very orbiter that she would one day fly. “Kind of a neat connection,” Metcalf-Lindenburger noted. “It just happened by chance, but it was really cool chance that it happened.”

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Situated 63 feet (19 meters) below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Reef Base habitat, off the coast of Key Largo, Fla., the facility would support Metcalf-Lindenburger and her NEEMO-16 crewmates—JAXA astronaut Kimiya Yui, Cornell University planetary scientist Steve Squyres and European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Tim Peake—for 12 days from 11 June 2012 as they worked to test innovative solutions to engineering challenges, allowing astronauts to eventually explore asteroids. “As if the prospect of living for 12 days underwater wasn’t exciting enough, it gets better,” exulted Peake in an ESA blog. “The aim of NEEMO-16 is to simulate a future mission to an asteroid. This is the current focus for NASA’s first manned mission into deep space, venturing beyond the Moon’s orbit and once more pushing the boundary of human presence in our Solar System.”

We need to venture to the Moon before going anywhere else. If human divers are ever to explore the subsurface oceans of the gas giant moons NASA needs to dump the dead end of LEO and return to the Moon. Only on the Moon can the water-as-radiation-shielding be acquired and the nuclear systems of a true spaceship be assembled, tested, and launched on multi-year missions. LEO is the worst place to go.

Astronaut Dottie Metcalf-Lindenburger

A concerned physician referred me to you when I mentioned losing contact with Rusty Schweickart

and Dave Morrison during a lengthy hospital stay. (email to NASA/B6-12 has brought no response.)

My full-time focus on meteorite-formed landforms since 1998 has produced a considerable volume

of data regarding the 21 recent ( late ice age) impacts of 100 to 300 m size that I’ve identified.

Discussions with Mark Boslough, Bob Eberle and Nadine Barlow were not useful toward illustrating

the mechanisms that caused these to create a million plus secondary imprints while leaving only six

land craters, none of which have been identified as such to date. (Well, they are underwater basins.)

My favorite doctors of USCD strongly urged that I either;

– publish a summary of my 16,000+ files immediately,

– download my mental computer’s contents to NASA, or

-sit with a bevy of students not yet locked into false premises. outdated theories or concepts that

cannot stand up to commonsense analysis. They pointed out that posthumous communication has

not yet been proven both reliable and accurate.

I prefer their last option, having learned at U-Wis 55 years ago that high-altitude educators and

researchers only rarely have clear comprehension of ground-level interactions with ETOs.

Gene Shoemaker seems to have been the last sensible researcher in my narrow field of study.

A few energetic youngsters would sort and present my data clearly enough so that even a Professor

can understand the interacting mechanisms and so revise literature that’s leading students astray.

Your recommendation of a source for these would be greatly appreciated. My verbal skills have been

impaired so I’ve not browsed local schools but I can relocate temporarily if that would be productive.

Jim Marple

jamesmarple66@yahoo.com

San Diego 858/603-2539