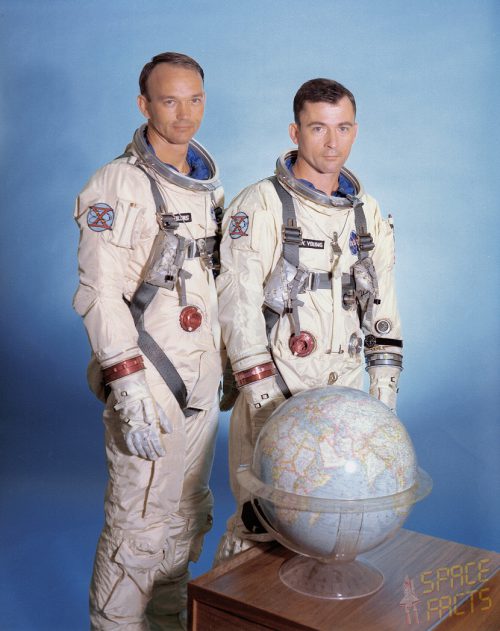

Half a century has now passed since Gemini X astronauts John Young and Mike Collins paved the way for humanity’s voyage to the Moon by accomplishing a remarkable raft of achievements. Launched precisely on time on the afternoon of 18 July 1966, the two astronauts—both of whom would journey to lunar distance later in their respective careers—successfully performed rendezvous with two unpiloted Gemini-Agena Target Vehicles (GATVs), physically docked with one of them, supported the first “space switch” to boost themselves to a higher orbit, and became the first crew in history to perform two sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA). However, an unlucky set of circumstances conspired to make both of Collins’ spacewalks unrecorded on film.

As detailed in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, Young and Collins rocketed into orbit, precisely on time, and within six hours of launch had rendezvoused and docked with their Agena target, tail-numbered “GATV-5005.” The Agena then employed its engine to boost the combo to an apogee of 474 miles (763 km), far higher than any previous manned spacecraft, and far higher than the 294 miles (473 km) of then-record-holders, Voskhod-2 cosmonauts Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov. In doing so, this marked the first “space switch,” with the crew subjected to “eyeballs-out” acceleration forces. “The light was something fierce,” Young reflected later, “and the acceleration was pretty good.” Their next quarry was the now-dead GATV-5003 Agena, left in orbit after the partially successful docking by Gemini VIII astronauts Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott in March 1966.

Early on the second day of their mission, Young performed a second “burn” of GATV-5005’s engine to reduce Gemini X’s velocity and lower its apogee to create better conditions for the second rendezvous. After 24 hours in microgravity, the 1-G acceleration was more noticeable than that of the previous day. (According to Young, it was “the biggest 1-G we ever saw!”) By the time it ended, the astronauts were trailing GATV-5003 by less than 1,100 miles (1,800 km). They also busied themselves with scientific experiments, several of which focused upon radiation monitoring of the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA)—the region in which the lowermost portion of the Van Allen Belts reach their closest to the surface—and around the spacecraft itself. “I only know that if I ever develop eye cataracts,” wrote Collins in his memoir, Carrying the Fire, “I will try to blame it on Gemini X!”

In fact, the astronauts’ radiation exposure was relatively benign, to such an extent that investigators on the ground jokingly accused them of switching their detectors off. Even the levels whilst passing through the SAA were lower than anticipated. Not only did it appear that the detectors had been turned off, but so too were Young and Collins’ voices. Neither man had time for idle conversation, with so much work on their hands, but at one stage they were asked by Deke Slayton—a fellow astronaut and then-head of Flight Crew Operations—to “do a little more talking from here on.” Young replied in his usual deadpan manner: “Okay, boss. What do you want us to talk about?”

Approaching orbital dusk on the afternoon of 19 July, Collins opened the hatch above his head and poked himself into space for EVA-1. Known as a “Stand-Up EVA,” he set up a general-purpose camera to examine ultraviolet radiation emissions from distant stars, specifically from the southern part of the Milky Way galaxy. In total, he acquired 32 images. “The stars are everywhere,” Collins later wrote, “above me on all sides, even below me somewhat, down there next to the obscure horizon. The stars are bright and they are steady.” Passing into orbital nighttime, he could see little of Earth, save for the blue-gray tint of water, cloud, and land.

Next, he set to work photographing swatches of red, yellow, blue, and gray on a titanium panel to determine the ability of film to adequately record colors in space. Unfortunately, Collins was unable to complete this task, for his eyes involuntarily filled with tears. So too did Young’s eyes. “That’s all we need,” Collins remembered later, “two blind men whistling along with the door open, unable to read checklists or see hatch handles or floating obstructions!” Initial suggestions from Mission Control that urine may have contaminated their oxygen supply were flatly rejected by the astronauts, who considered it more plausible that a new anti-fogging compound on the inside faces of their suit visors may have caused the irritation. The EVA ended a few minutes early, after 49 minutes, and it later became clear that lithium hydroxide—used to scrub carbon dioxide from the cabin atmosphere—had mistakenly been pumped into the astronauts’ suits.

“I was crying all night,” Young later quipped. “But I didn’t say anything about it. I figured I’d be called a sissy!”

Two days after launch, on the afternoon of 20 July 1966, Gemini X undocked from GATV-5005 and Young described the steadily departing Agena as resembling “a big boxcar in front of you.” Its departure also gave them a better view of their surroundings, for with the massive GATV docked at their spacecraft’s nose, their visibility had been “practically zilch.” Several hours later, Young reported his first sighting of GATV-5003, which had been left unattended in orbit since Armstrong and Scott’s mission in March. In spite of the length of time it had been in space, GATV-5003 appeared very stable. All maneuvers were manually done, and reliant upon eyeballs alone, since the long-dead Agena was giving off no radar signals and its lights had long since ceased to function.

Heading toward orbital sunrise, Collins opened his hatch for the second time and became the first human to perform two sessions of extravehicular activity. His three predecessors—Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, the first man to walk in space, and U.S. astronauts Ed White and Gene Cernan—had all ventured outside their respective vehicles on a single occasion. Equipped with a hand-held “zip-gun,” Collins maneuvered himself over to GATV-5003 and removed a micrometeoroid detector, which was one of the tasks originally slated for Dave Scott to complete. He then moved back to Gemini X to replenish the zip-gun’s nitrogen supply, as Young drew the spacecraft closer to the Agena.

From Young’s perspective, the task was complicated by having to pay close attention to three objects: the Gemini, the Agena, and his spacewalking crewmate, as well as keeping sunlight from falling onto Collins’ ejection seat on the right side of the cabin. If it heated up too much, the pyrotechnics might fail, taking both of Gemini X’s hatches and Young’s own left-side seat with it. Although Young had four cameras to photograph Collins’ spacewalk, by his own admission, “none of ’em were workin’!” Nor was Collins able to photograph a human being’s first contact in space with another space vehicle, for his hand-held Hasselblad had drifted off as he struggled to control his snake-like safety tether. Returning inside Gemini X’s cabin after 39 minutes, Collins had to be helped by Young out of the tangle of tether.

A day later, on the afternoon of 21 July 1966, Young and Collins were bobbing in the waters of the western Atlantic Ocean, having wrapped up the Gemini program’s eighth piloted mission. They splashed down so close to the prime recovery vessel, U.S.S. Guadalcanal—just 3.3 miles (5.4 km)—that the ship’s crew was able to watch Gemini X descending through the clouds beneath its parachutes.

And the landing of Gemini X, exactly three years before the first boots reached the lunar surface, cleared a number of significant milestones as America’s pressed ahead with its national goal of landing humans on the Moon before 1970. During their three days in space, Young and Collins had demonstrated rendezvous techniques, formation maneuvering, docking, and spacewalking. Moreover, their usage of GATV-5005 as a switch engine had important implications for future missions. And for both men, their subsequent careers would carry them to lunar distance: Young as one of only three humans to have flown twice to the Moon, and Collins aboard the historic Apollo 11 mission.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 55th anniversary of Liberty Bell 7, the 15-minute suborbital flight of Virgil “Gus” Grissom in July 1961, a mission which almost ended in the astronaut’s death.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

These articles are spectacular. I have been a space historian for over 50 years and I am enjoying these writings immensely. Thank you and please keep up the fantastic work.

I also agree that this was an excellent series on the Gemini 10 mission. It also reminds us of the loss of the TV transmission from Apollo 12 when the camera was inadvertently pointed at the sun. Excellent job as usual, Ben!