Twenty-five years ago, tonight, six astronauts spent their last night on Earth ahead of a scheduled liftoff early the following morning on a complex mission to radar-map the Home Planet in unprecedented detail. The second Space Radar Laboratory (SRL-2)—equipped with the powerful Shuttle Imaging Radar (SIR-C) and the X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (X-SAR)—was flying only a few months after SRL-1, in order to gather data and capture a glimpse of terrestrial change in the late spring and late summer of the year. And it would not be unrealistic to suppose that STS-68 Commander Mike Baker and his crew may have had a fluttering of nerves as they steeled themselves to rocket off the planet next day.

But on this occasion they would do so only six weeks after suffering one of the hairiest launch-pad aborts in history: an abort which saw them come closer to liftoff than any other shuttle crew, without actually breaking the shackles of Earth, igniting the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) and launching into space. As detailed in last weekend’s AmericaSpace history feature, Baker and his crew aborted just 1.9 seconds prior to SRB ignition. So close were they to launching that the famous countdown clock at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Press Site actually displayed “T+00:00:00” on its face…and yet stunned onlookers beheld only an ominous grey cloud as the shuttle’s engines rose in a booming crescendo, then fell to an ethereal silence.

For one of the crew, Mission Specialist Dan Bursch, it was the second time in his career that he had endured a so-called Redundant Set Launch Sequencer (RSLS) abort in the final seconds before liftoff. Bursch had been aboard STS-51 a year earlier, when a similar pad abort took place. As such, his crewmates lightheartedly felt that if Endeavour did not know that the unlucky Bursch was aboard, they might actually get to fly. When the six astronauts—Baker, Bursch, Payload Commander Tom Jones, Mission Specialists Steve Smith and Jeff Wisoff and Pilot Terry Wilcutt—arrived at the Cape a couple of days before launch, they ensured that Bursch wore a suitable “Groucho Marx” disguise. But matters did not improve, for all of them, except Wisoff, had colds.

Still, Endeavour proved charmed on the second time around and roared smoothly aloft at 7:16 a.m. EDT. “It felt great on-board,” seasoned shuttle veteran Baker recalled, noting that they “jumped right up to 2.5 G”, whilst Wilcutt—making his first flight—pointed out that “the expression kicked off the pad is an accurate one”. The rise to orbit was exceptionally smooth and the astronauts quickly set to work configuring their ship for operations and activation of the SRL-2 payload in the bay. Jones later recalled his relief at having taken medication to hedge against space sickness before launch, but less fortunate was “rookie” Steve Smith, who needed a shot of the anti-nausea drug Phenergan.

Luckily, Smith, Bursch and Jones—STS-68’s “blue” shift—bedded down for their first night’s sleep soon after reaching orbit. It was their red shift crewmates Baker, Wilcutt and Wisoff who worked to activate the SRL-2 payload and made its inaugural observations. Endeavour flew over many of the same sites that SRL-1 did, enabling the SIR-C and X-SAR research teams to examine seasonal changes. In addition to its enormous scientific yield, the first radar mission had demonstrated that it could acquire high-resolution data and endure adjustments to its timeline to cater for new events on the ground. For example, SRL-1 observed severe floodwaters in the mid-western United States and in Thoringen, Germany, as well as taking three different views of Tropical Cyclone Odille as it formed and contorted in the Pacific Ocean. Snow and ice classification maps had been assembled from data over a “supersite” at Oetztal in Austria and the late-summer flight of STS-68 offered a chance to observe the Patagonian district of southern Chile, home to the largest glaciers and ice fields in South America.

Volcanic sites were a key objective. During SRL-1, the radars had observed Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines—which erupted in mid-1991, affecting global stratospheric temperatures and aerosol levels—and several locations in the Galapagos Islands. Imagery of Pinatubo during the summer monsoon season, when new mud flows were predicted to occur, was high on SRL-2’s list of priorities.

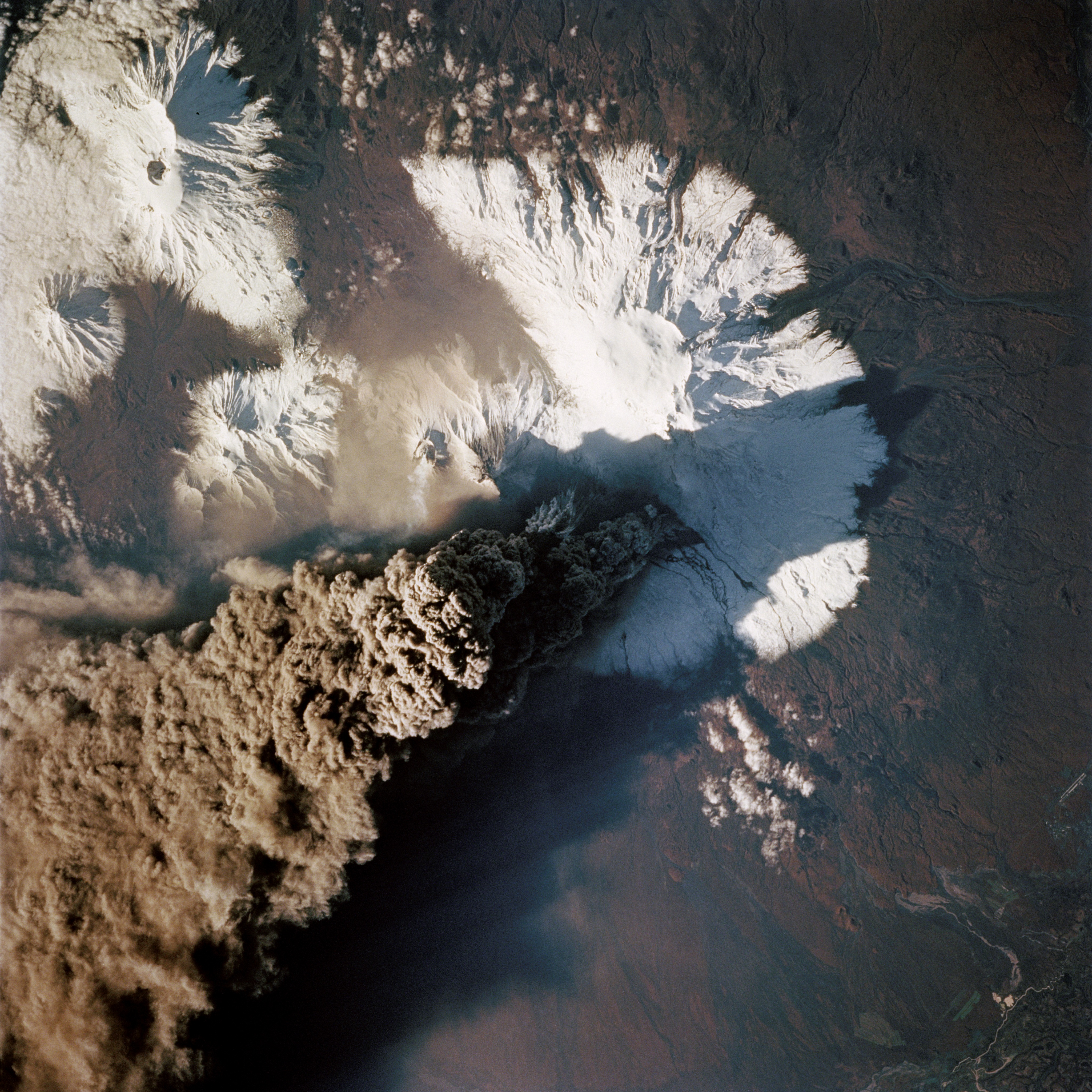

However, early in the flight, a serendipitous observation of an eruption in the Russian Far East was made. Klyuchevskaya Sopka is the highest mountain on the Kamchatka Peninsula and the highest active volcano in the whole of Eurasia; it burst into fiery life shortly after Endeavour entered orbit, giving the STS-68 crew a surprise. They saw its tremendous black plume on the horizon, ahead of their flight path. At first, it looked like a vast thunderhead. Baker was first to recognize it as a volcano. Wisoff was amazed. “It shows how much change nature can produce in a short period of time,” he recalled in a Smithsonian interview. “You had this huge eruption, but then by the end of the flight it had largely stopped erupting. There was still a small smoke trail, but it had re-snowed on top of the soot. In the span of ten days, it was almost white again!”

Tom Jones, too, remembered the event lucidly in his book, Skywalking. In his recollection, it was the red team who called the blues up to the flight deck to see the eruption. Like Wisoff, Jones thought at first that it was an anvil-shaped thunderstorm or a clump of dust lofted by high winds, but the smoke-free nature of the surrounding terrain (and the location, Kamchatka) quickly assured them that it was a volcano. Jones had seen it during his SRL-1 radar-passes, but six months earlier Klyuchevskaya had been silent and still under a blanket of April snow. Now, at the end of September, it was in full fury, unleashing an ash-cloud to over 50,000 feet (15,000 meters), which was blown far to the east by the jet stream.

“We soon had every camera…zeroed-in on the eruption,” Jones wrote, “as Endeavour gave us a dramatic, down-the-throat view of this impressive geology lesson.” In another example of responding to unforeseen events on the ground, the SRL-2 team reprioritized several radar passes to scan the eruption as many as three times daily and Jones hoped that this might lead to permanent, Earth-orbiting satellites to watch for volcanic events.

“At shift handover we would meet and discuss any anomalies or changes to the plan as well as share stories of the most exciting observations during the last shift,” Wisoff told AmericaSpace. “One such observation was seeing the volcano erupt on the Kamchatka Peninsula. On shift we tended the data recorders as needed and recorded our observations of the weather conditions over data sites since stormy weather, heavy smoke or other atmospheric conditions might affect the quality of the data. In addition to the data collection, the shifts took care of the nominal orbiter care and feeding, and we conducted a few other onboard payload experiments.”

By the sixth day of STS-68, as expected, consumables remained at a level sufficient to enable the Mission Management Team to formally extend the ten-day flight by an additional 24 hours. Endeavour would now land on 11 October. (She would actually touch down at Edwards Air Force in California at 10:02 a.m. PDT, after thick cloud at KSC obliged NASA to switch landing sites.) The radar’s payload recorders performed well, although one had to be removed and replaced after it failed to play back properly. Rerouting the data stream between the remaining machines, the repair by Smith and Wisoff occurred over a comparatively “empty” Pacific orbital pass. “With the radar inactive over the ocean,” wrote Jones, “Steve and Jeff were well into the repair before we made landfall again. An hour later, the swap was complete and the pair had stowed their wrenches and screwdrivers with almost no loss in science data.”

Years later, Wisoff remembered the repair well, in comments provided to AmericaSpace. “During flight one the payload data recorders failed which could cause the mission to lose some of its precious data,” he explained. “Being on opposite shifts, Steve Smith and I had both been trained to replace it with a spare we had onboard. It was decided that by installing the spare during crew handover when both Steve and I could work together, we might be able to finish the replacement while passing over the Pacific Ocean where little data would be lost. The whole crew pitched in and created an efficient operation like a race car pit stop. The recorder was successfully replaced over the Pacific Ocean.”

Overall, more than 110 hours of radar observations were acquired in 950 data takes, recorded on 199 digital tapes, covering an area of over 32 million square miles (83 million square kilometers). One of the bonuses of flying the mission a second time was the ability to use “interferometry” during the final three days of STS-68 and SIR-C/X-SAR data was used to record topographical changes between April and October in California’s Long Valley Caldera and Hawaii’s Kilauea. Interferometry is analogous to stereo photography, although to achieve it between STS-59 and STS-68 demanded that their repeat orbital paths be separated by a mere 200 feet (60 meters). “Mission Control and our crew combined to perform the most precise orbital maneuvers ever seen in the shuttle program,” explained Jones, “putting Endeavour in an orbit for the first six days that nearly matched our SRL-1 flight path.” At times, the respective flight paths differed by less than 30 feet (10 meters).

In their post-flight press conference, Baker paid tribute to Bursch, who had worked tirelessly with the Flight Dynamics Officer (FIDO) teams on the ground to put together the 14 “trim burns” needed for the interferometry data-takes. “Dan put together a nice procedure, along with the help of the FIDOs, to get these burns trimmed down to an unprecedented accuracy of about 0.5 fps,” he recalled. “We were able to perform those burns and get the orbiter to within 200 feet of where it was the day before and also within 200 feet of where Endeavour was in April.”

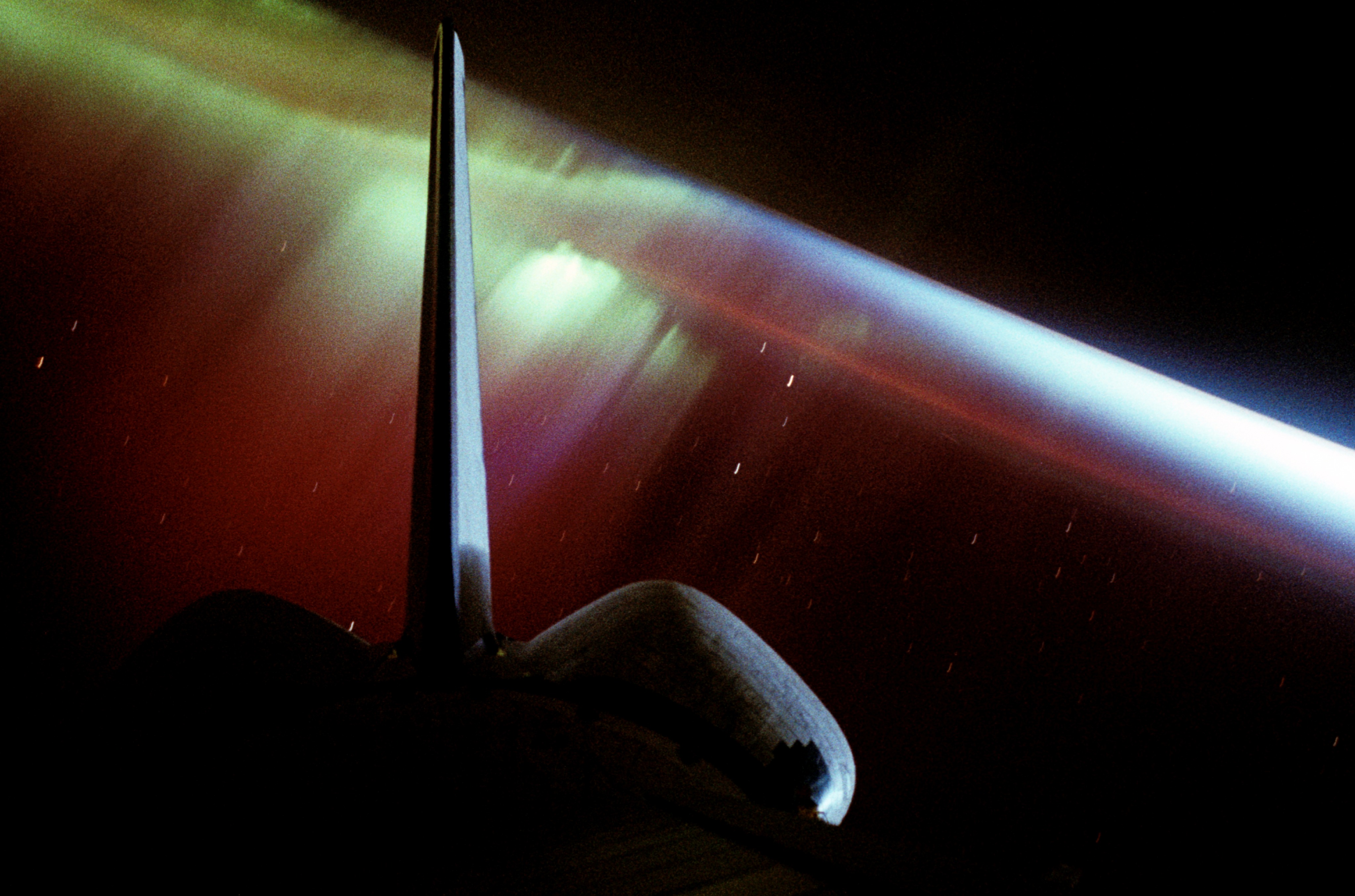

Also flawless were operations with the Measurement of Air Pollution from Satellite (MAPS), which gathered 256 hours of data and achieved a 100-percent success rate. In total, more than 14,000 photographs were taken in support of radar and MAPS science and, according to Wisoff, by the end of STS-68 enough data had been collected to fill a stack of floppy disks standing 15 miles (24 km) high. And with over 400 maneuvers conducted during the flight, the red and blue teams totaled over 22,000 keystrokes.

MAPS reinforced the STS-59 consensus that although carbon monoxide concentrations in the southern hemisphere were relatively low, with exceptionally clean air, the situation worsened in the northern hemisphere, with the highest concentrations to the north of the 40-degree latitudinal band. MAPS also observed intentionally-set fires, monitored by scientists from the University of Iowa and the Canadian Forest Service, to assess their wind fields, thermal evolution and carbon monoxide emissions and calibrate SRL-2 infrared data. “These fires,” noted NASA in one of its STS-68 news releases, “were planned in advance of the mission and would have been set for forest-management purposes, even if the shuttle mission were not in progress.” Other controlled observations included an experimental “spill” of diesel oil and algae products in the North Sea to test SRL-2’s capacity to differentiate between the spill and naturally-produced film caused by the products of fish and plankton.

“The SRL mission successfully measured the movement of volcano faces from orbit, revealed lost caravan trails under the Sahara Desert and successfully identified natural resources like tree stands from orbit,” Wisoff told AmericaSpace of STS-68’s legacy. “It demonstrated that space platforms have the potential to play an important role in early warning systems for volcanic and earthquake detection as well as supplying critical earth resource management data.”

Orbital life aboard Endeavour herself was exceptionally smooth…and humorous for the irreverent STS-68 crew. Smith remembered that the two shifts “ate on the fly” for lunch, but did have more time for dinner on the middeck. During training, at reviews of the food menus, Baker expressed his fondness for smoked turkey, which he enjoyed folding into tortillas. Now, in space, this love returned to haunt him. “When Bakes asked what was for dinner, the answer nearly always was smoked turkey,” wrote Jones. “Noticing our escalating laughter, by the third day our commander was convinced he was the victim of a practical joke instigated either by us or some of his 1985 astronaut classmates. We maintained our innocence and post-flight investigation showed the on-board turkey surplus was his own doing!” To be fair, an entire pantry of other goodies awaited them—shrimp cocktails, horseradish, beef tips and mushrooms, spaghetti and meat sauce, buttered asparagus, strawberries, chocolate puddings—but Jones could not help but wonder what turkey-loving Baker ate for his Thanksgiving meal…