A mission (not) shrouded in secrecy began on this day in 1985. Shuttle Atlantis, on the very first flight of her long and glittering career, rose ponderously from historic Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, to kick off one of a handful of voyages which—even nearly four decades later—remain, for the most part, unknown.

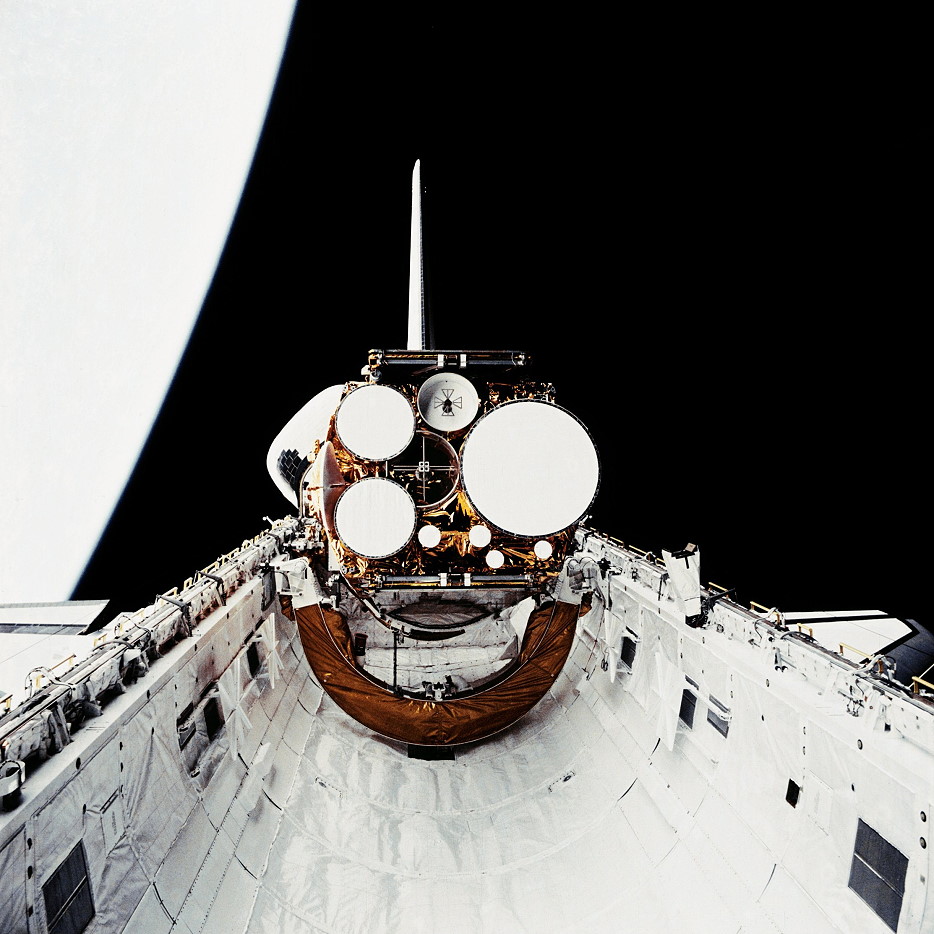

Commanded by Karol “Bo” Bobko, who died in August, Atlantis’ STS-51J crew included pilot Ron Grabe, mission specialists Dave Hilmers and Bob Stewart and Manned Spaceflight Engineer (MSE) Bill Pailes. Theirs was a highly classified flight on behalf of the Department of Defense and is now known to have deployed a pair of Defense Support Communications System (DSCS)-III satellites, dual-stacked atop a Boeing-built Inertial Upper Stage (IUS). In fact, pictures of the satellites in Atlantis’ payload bay remain the only in-flight imagery of any classified shuttle primary cargo ever released to the general public.

The “core” NASA crew of Bobko, Grabe, Hilmers and Stewart had been assigned in November 1983, with fellow astronaut Mike Mullane, to a so-called “DoD Standby” mission, ready to support future Department of Defense flights. “Even those of us on the crew didn’t know what that meant,” wrote Hilmers in his memoir, Man on a Mission. “It didn’t have an official flight number and it hadn’t been assigned to any of the three orbiters that were in the fleet at the time.”

For several months, the men trained, added Hilmers, “for tasks that might or might not actually take place”. Finally, in February 1985 Bobko, Grabe, Hilmers and Stewart were named to STS-51J, tracking a launch the following September as the first flight of the new shuttle Atlantis. Pailes later joined them as the mission’s single payload specialist.

Remarkably, STS-51J suffered from only minor slippage in its flight schedule. The new shuttle arrived at KSC in April 1985 and was put directly into processing, before being mated to her External Tank (ET) and twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) and rolled out to the launch pad in August.

“We certainly monitored the progress of Atlantis closely, but we didn’t have a lot of direct involvement in the processing and testing,” Hilmers previously told AmericaSpace. “We made one trip to Palmdale, Calif., to see Atlantis before it went to KSC and we went to the Cape for some final testing. However, we were too busy training to get too involved in the day-to-day processing.”

In Hilmers’ recollection, STS-51J’s crew was a religious group. “The five of us were fairly quiet guys, who didn’t make a lot of noise, Bo included,” he wrote. “We didn’t raise much of a ruckus over anything and, as a result, we all got along really well.”

With Bobko, Grabe and Pailes representing the Air Force, Hilmers the Marine Corps and Stewart—the first Purple Heart-holder ever to travel into space—the first Army astronaut, their military pedigree gave them a common thread. This produced some inter-service rivalry, including an instance when Hilmers ribbed Stewart over the “toughness” of his Army basic training, “down at the Holiday Inn Express”.

Speaking to AmericaSpace, Hilmers described his STS-51J crewmates as “kind of mild-mannered men”, with Bobko and Stewart, the only spaceflight veterans, as team leaders. He said that although they rarely had reunions, “we bump into each other, now and then”, adding that Grabe’s daughter was later a medical student at Baylor College of Medicine after Hilmers became a professor there. “She did some research with me,” he recalled.

As their military brotherhood kept the crew unified, so too did their faith. “Of the four crews on which I served, 51J was probably the most uniformly religious,” Hilmers wrote. “A group of us in the Astronaut Office routinely held Bible studies throughout my time with the agency, and on this flight in particular, we all seemed to be on the same basic page when it came to our faith.” To Hilmers, it “meant the world” when the five of them shared a prayer on the morning of 3 October 1985, just before heading to the launch pad and Atlantis.

Despite the shroud of secrecy usually emplaced upon Department of Defense shuttle flights, STS-51J’s payload was pretty well known before Atlantis rose to orbit at 11:15 a.m. EST that day. Details had appeared in Aviation Week before STS-51J ended and deployment images of the twin $160 million DSCS-IIIs have long since been declassified and are now firmly in the public domain, largely because they were military communications satellites and not “deep-black” reconnaissance or intelligence-gathering ones.

But STS-51J began with an upset wife. Management consultant Diane Bobko was particularly irritated, as her husband could tell her little about the mission.

“Bo,” she said one morning at the breakfast table. “You’re not telling me exactly what day you’re going to land, but I think it’s going to be pretty close to a day I have a program in Baltimore.”

“Diane, it’s the first flight of a new vehicle,” her husband replied. “Probably the safest thing you can do is go ahead and schedule that right now.”

Privately, Bobko was convinced that STS-51J would meet with delay. But it did not.

The nature of STS-51J’s payload as a pair of DSCS-IIIs (nicknamed “the discus”) was declassified in the summer of 1998 and lent a measure of credence to Bobko’s later claim that, for all its secrecy, the mission was little more than just another “vanilla” satellite deployment flight.

The satellites had long been an anchor in the Pentagon’s global communications network, operating in geostationary orbit with around a half-dozen super-high-frequency transponders for secure voice and data transmissions and high-priority command and data links between government officials, military leaders and battlefield commanders. The Air Force later admitted it had launched two DSCS-IIIs in 1985 and according to space analyst Dwayne Day “the only launch that year that fit was the Atlantis mission”.

Subsequent documentation highlighted that the DSCS-III satellites had been deployed during “a” shuttle flight but refused to name the flight…even though it could be quite straightforwardly inferred. “Military secrecy can be bizarre at times,” wrote Day. “Like acknowledging that there is a blue sky and that the sky can be blue, but never saying that the sky is blue.”

Each of the roughly cube-shaped satellites possessed two articulated solar panels and weighed in the region of 5,730 pounds (2,600 kilograms). With launch of STS-51J settled on 3 October 1985, NASA revealed a four-hour “window” from 10:20 a.m. EST through 2:20 p.m. EST, although the threat of offshore rain showers prompted Air Force meteorologists to predict only a 60-percent probability of acceptable conditions at T-0.

As well as this vague launch time, which only became known for certain when the famous countdown clock emerged from its final hold at T-9 minutes, the duration of STS-51J was also unclear, with at least one media outlet suggesting five or six days. Launch was held by 22 minutes due to a power controller issue with a liquid hydrogen prevalve in one of Atlantis’ main engines. Then, all at once, spectators were startled when the blank face of the countdown clock suddenly came alive and began ticking from T-9 minutes.

As liftoff neared, excitement increased. “We have Main Engine Start,” came the launch announcer’s call. “Four, three, two, one…ignition…and liftoff…Liftoff of Atlantis! A new orbiter joins the shuttle fleet and it has cleared the tower!”

Liftoff came at 11:15:30 a.m. EST. Unlike most other missions, where the Commander could be heard confirming the “Roll Program” maneuver, it was the Public Affairs Officer (PAO) who announced “Roll Program initiated; crew confirms roll maneuver,” as Atlantis embarked onto the proper heading for its 8.5-minute climb uphill.

This was followed by several other clipped acknowledgements during first-stage ascent: “26 seconds, beginning throttle-back to 65 percent, pass through the area of maximum aerodynamic pressure on the vehicle”. Then came confirmation that the SSMEs had returned to 104-percent rated performance, followed by “Crew given a Go at throttle-up” and “Commander Bobko acknowledging that Go at throttle-up.”

For Hilmers, seated behind Grabe in the Mission Specialist 1 seat on Atlantis’ flight deck, it was a moment he would never forget. “That first view of Earth from space was amazing,” he told AmericaSpace. “I remember how brilliant the first sunrise seemed. A more humorous incident occurred when I forgot to add water to the dehydrated sausage when it was my turn to cook breakfast. I was permanently taken off duty as the chef!”

After 97 hours and 44 minutes, STS-51J ended with a perfect landing at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., at 10:00:08 a.m. PST (1:00:08 p.m. EST) on 7 October 1985. As the fast-descending orbiter appeared on the desolate Mojave horizon, then alighted on Runway 23, the NASA PAO picked up the commentary: “Touchdown Main Gear … Touchdown Nose Wheel … and the fourth orbiter in NASA’s fleet, Atlantis, rolls out on landing, concluding Space Shuttle Mission 51J.”

And as it turned out, Diane Bobko was in California to meet her husband. Astonishingly, Atlantis had met with no significant delays, launched on time and landed on time. “So she was there to meet me in California,” Bobko remembered, “gave me a hug and then she had to leave right away to … drive down to Los Angeles to catch the airplane to go to Baltimore.”

Later that evening, Bobko was startled out of his sleep by a telephone call. It was his wife. Surely, if a vehicle as complex as the shuttle could fly on time, on its maiden voyage, then her domestic flight ought to have been trouble-free.

“You’re in Baltimore?” he asked.

“No,” she replied, glumly. “I’m still in Dallas, trying to get to Baltimore!”