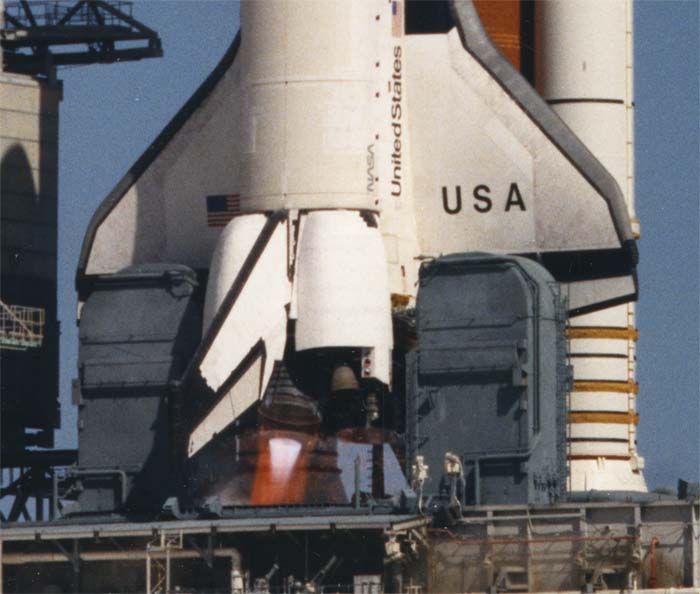

Thirty years ago, tonight, in the seconds leading up to 1:29 a.m. EDT on 8 April 1993, all eyes were on the three dark bells of Discovery’s Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) as they were readied for ignition. It would be the 16th flight by an orbiter which went on to become the most-flown member of NASA’s shuttle fleet—logging 39 missions by the time she returned to Earth for the last time in March 2011—but STS-56 took flight after several fraught days at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC).

Two weeks earlier, Discovery’s sister ship, Columbia, endured a harrowing shutdown of her own SSMEs, seconds before liftoff, and the STS-56 crew found themselves similarly impacted by the gremlins of misfortune. Yet Commander Ken Cameron, Pilot Steve Oswald and Mission Specialists Mike Foale, Ken “Taco” Cockrell and Ellen Ochoa would turn night into day across the marshy Space Coast and fly a spectacular nine-day voyage of scientific discovery, focused wholly upon the Home Planet.

In the aftermath of Columbia’s Redundant Set Launch Sequencer (RSLS) abort on 22 March, her STS-55 mission was stood down for more than a month, in order for corrective actions to be taken and her suite of engines removed and replaced. A few days later, NASA formally declared that STS-56 would take pole position and fly first in early April, targeting an opening launch attempt on the 6th.

Primary payload was the second Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science (ATLAS-2), an array of instruments affixed to an unpressurized Spacelab pallet in the shuttle’s payload bay to examine Earth’s atmosphere and climate and its interaction with the Sun. Timing was especially critical if the STS-56 crew were to observe seasonal changes between late spring and early summer in the Northern Hemisphere.

The countdown on the night of 6 April proceeded smoothly until the built-in hold at T-9 minutes, when an issue arose relating to higher-than-expected temperatures on a valve in Discovery’s No. 1 SSME. The clock was held for more than an hour, before controllers finally resumed the count at 1:23 a.m. EDT on the 7th.

At T-31 seconds, control of the countdown was handed off from the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) and primary commanding of all vehicle critical functions transitioned over to the shuttle’s on-board computers. The safe-and-arm devices on STS-56’s twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) were armed and Cameron and his crew braced for the enormous jolt of Main Engine Start at T-6.6 seconds.

But it never came.

At T-11 seconds, abruptly, the countdown was automatically halted and the launch attempt scrubbed. It subsequently became apparent that the hydrogen high-point bleed valve’s “closed” indicator was not present and—although the cause was traced to an instrumentation error, not a hardware malfunction—it breached Launch Commit Criteria (LCC) rules.

The disappointed astronauts climbed out of Discovery, unsure of when their next launch attempt might be. But fortune, for once, smiled on them. Engineering checks of the bleed valve revealed no problems and NASA felt able to reschedule another attempt for the wee hours of 8 April.

This time, nothing conspired against STS-56 and the crew were strapped into their seats, with Cameron, Oswald, Ochoa and Cockrell on the flight deck and Foale downstairs in the middeck. Lifting off at 1:29 a.m. EDT, Discovery created an artificial sunrise across KSC, as the mission marked only the eighth nocturnal launch of the shuttle program.

With Cockrell and Ochoa both on their first flights, and STS-56’s three veterans having previously launched in the daytime, it was a wholly different dynamic. “We cleared the tower right on time, right at the very opening of the window and these things are spectacular enough in the daytime,” Oswald recalled. “They’re even better at night!”

During the Roll Program maneuver, ten seconds after liftoff—as the shuttle stack oriented itself onto the proper alignment for its 8.5-minute climb to orbit—the upstairs crew could easily see the reflection of the SRB exhaust plumes off the clouds. For Foale, seated downstairs on the darkened middeck, there was little more than a faceful of lockers for company.

“The ascent first stage is always a little bit of a rough ride, going uphill,” continued Oswald, “but the boosters and the main engines performed absolutely flawlessly.” He remembered SRB separation from his previous mission, likening it to a train wreck, but the difference in brightness when flying an ascent at night was profound.

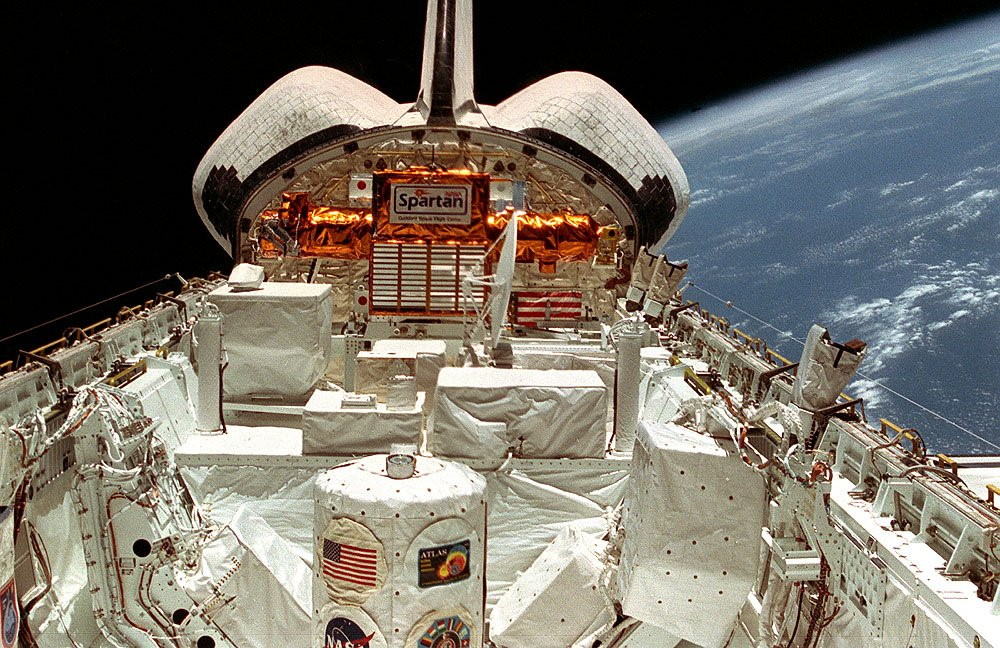

The spectacular launch thus kicked off a spectacular nine days in space. The five astronauts ran ATLAS-2 around the clock—with Red Team crewmen Cockrell and Foale monitoring the systems during their 12-hour shift and Blue Team counterparts Cameron, Oswald and Ochoa doing likewise for their 12 hours on duty—and deployed and retrieved the Spartan solar physics satellite with the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm.

The box-shaped Spartan, which now resides on display at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, D.C., spent two days in free flight, observing the Sun’s corona. The crew performed three separation “burns” to back away from the payload to a distance of 100 miles (160 kilometers).

They later returned to retrieve it with the RMS. During nominal ATLAS-2 science operations, the arm was held in an “extended park” position—“about 160 degrees of yaw,” Oswald recounted—to keep it out of the way of payload observations of the Sun or the limb of the Home Planet.

All told, STS-56 gathered atmospheric data over 94 percent of Earth, including detailed stratospheric measurements of the Arctic Region. Unsatisfactory weather conditions at KSC on 16 April forced the crew to spend an additional 24 hours in orbit, although “forced” proved an inaccurate descriptor, for the astronauts loved it.

“It had been a pretty hectic pace there, and we were all a little bit tired out, and the wave-off day gave us a chance to rest up and look out the window and shoot up what little film we had left,” said Oswald. “We joked that we’d probably have to plan one of these wave-off days into every flight and really get a chance to enjoy the environment.”

Those moments of enjoyment included Ochoa, an accomplished flutist, serenading her crewmates with various military hymns, as Cockrell and Foale kept a ball of drinking water floating in perfect harmony, before gobbling it down. But on 17 April, all good things came to an end, as Discovery swept perfectly in Florida and alighted on Runway 33 of the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at 5:37 p.m. EDT, wrapping up a spectacular voyage for NASA’s Mission to Planet Earth.

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:“Sure Hope I Like This”: Remembering a Complex Shuttle Mission, 30 Years On - AmericaSpace