Yesterday afternoon the comet that has caught the world’s attention, ISON, went through a hellish encounter with the Sun. After falling for millions of years from the deepest, darkest depths of the outer Solar System’s Oort cloud—which is believed to extend halfway to the nearest star—ISON came within 730,000 miles of the Sun’s surface, slingshotting around it at over 200 miles per second while many here at home were preparing Thanksgiving dinner with family and friends. But did the sungrazer survive its extreme close encounter with our star?

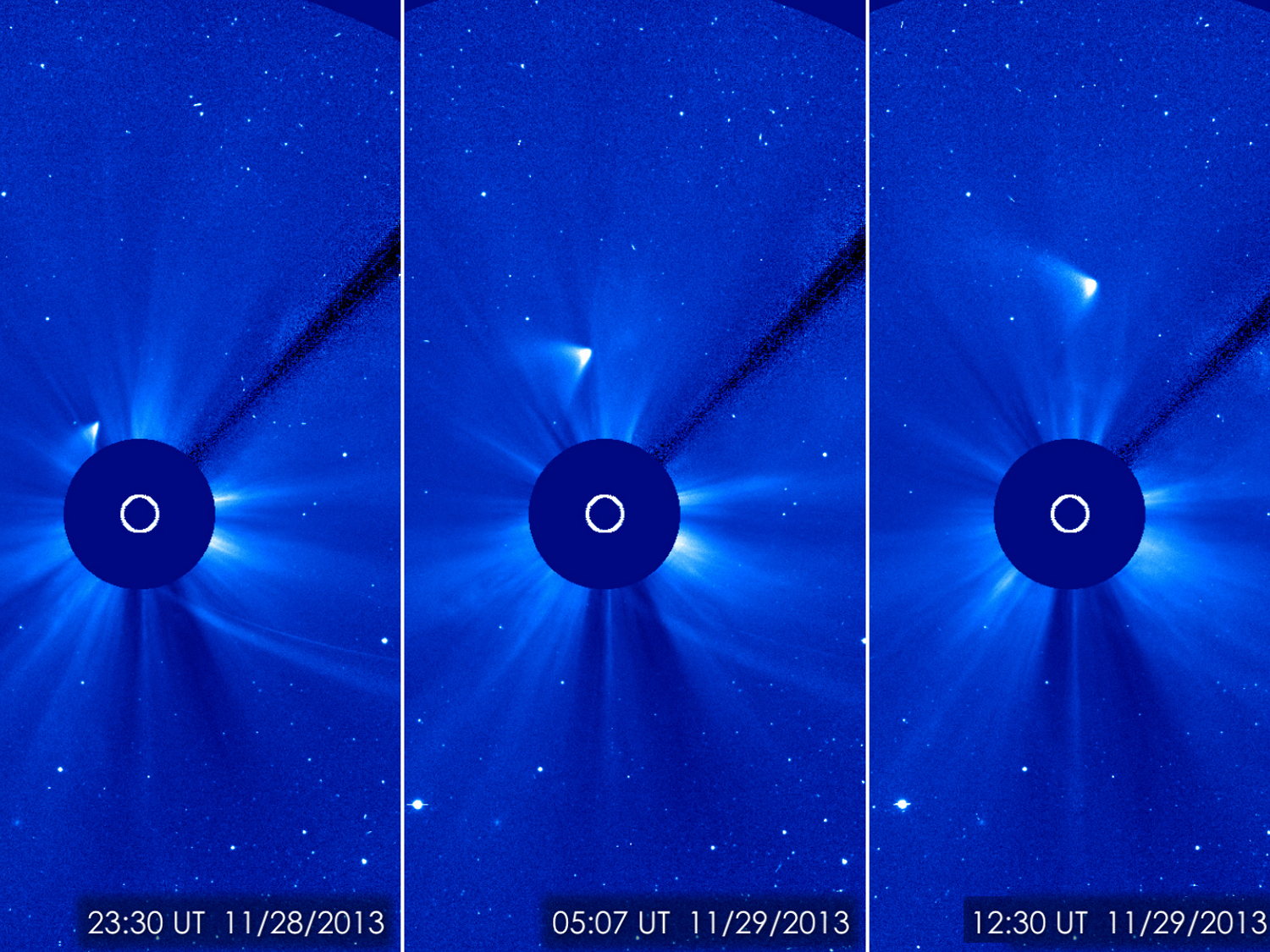

As the 4-5 billion-year-old comet approached its moment of truth, NASA’s STEREO satellite, the European Space Agency/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft, and the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) all recorded ISON’s fiery kamikaze death dive. At 1:45 p.m. EST (18:25 UT) comet ISON made its closest approach to our star, known as perihelion, then vanished. All that remained was a long tail smeared across millions of miles of space, and astronomers—even NASA and the ESA—concluded that ISON had in fact succumbed to the intense gravitational forces and extreme heat it encountered as it blasted through the solar corona.

“After impressing us yesterday, comet ISON faded dramatically overnight, and left us with a comet with no apparent nucleus in the SOHO/LASCO C2 images,” says Karl Battams of the Naval Research Laboratory, who is also the solar spacecraft lead for NASA’s Comet ISON Observing Campaign and the leading authority on all things ISON. “As the comet plunged through the solar atmosphere, and failed to put on a show in the SDO images, we understandably concluded that ISON had succumbed to its passage and died a fiery death. Except it didn’t. Well, maybe… “

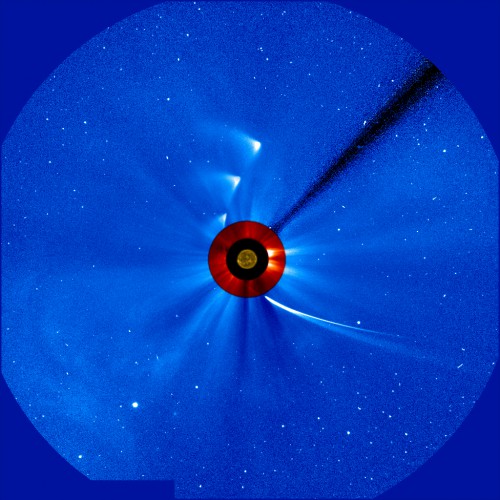

ISON, in typical fashion, had yet another surprise to go with the long list of other surprises it has given us since being discovered in 2012 by amateur Russian astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok. Something survived, which is now obvious in the images NASA and ESA solar observing spacecraft are sending back. The comet was not completely destroyed as initial observations had led researchers to believe, but how much of the comet still remains is unknown at this time.

“After perihelion, a very faint smudge of dust appeared in the LASCO C2 images along ISON’s orbit. This surprised us a little, but we have seen puffs of dust from Sungrazer tails, so it didn’t surprise us enormously and didn’t change our diagnosis,” says Battams in his latest blog post on the Comet ISON Observing Campaign website. “We watched and waited for that dust trail to fade away. Except it didn’t. Now, in the latest LASCO C3 images, we are seeing something beginning to gradually brighten up again.”

Battams adds: “As comet ISON plunged towards the Sun, it began to fall apart, losing not giant fragments but at least a lot of reasonably sized chunks. There’s evidence of very large dust in the form of that long thin tail we saw in the LASCO C2 images. Then, as ISON plunged through the corona, it continued to fall apart and vaporize, and lost its coma and tail completely just like Lovejoy did in 2011. (We have our theories as to why it didn’t show up in the SDO images but that’s not our story to tell – the SDO team will do that.) Then, what emerged from the Sun was a small but perhaps somewhat coherent nucleus, that has resumed emitting dust and gas for at least the time being. In essence, the tail is growing back, as Lovejoy’s did.”

The bottom line, at least at this time, is that the data and imagery support the theory that at least a part of ISON’s nucleus, or head, remains in tact and continues to actively release material.

“We need to observe it for a few days to get a feel for its behavior,” says Battams. “It’s throwing off dust and (probably) gas, but we don’t know how long it can sustain that.”

ISON has understandably confused amateur and professional astronomers alike, especially during the weeks leading up to perihelion. ISON dramatically brightened and then dimmed, repeatedly, through the month of November, instead of gradually increasing in brightness as is usually expected of a comet approaching the Sun. But, unlike other comets observed in previous years, ISON is a first-time visitor. Making its first trip through the inner Solar System presents the science community with an incredibly rare opportunity to study this time capsule, which is, or at least was, still coated with the frozen pristine matter that helped build the early Solar System and our Earth. Nobody has ever studied such an object, simply because there has not been such an opportunity at any point in recorded history, so naturally many surprises have been throwing off the experts, which is both frustrating and exciting.

“At this point, I refuse to make any further conclusions about this comet; it seems eager to confuse,” said Phil Plait, an astronomer who writes Slate’s Bad Astronomy blog and participated in a live Google+ hangout with Karl Battams during ISON’s violent trek around the Sun Thursday afternoon. “I’ve been hearing from comet specialists who are just as baffled… which is fantastic! If we knew what was going on, there’d be nothing more to learn. ISON’s nucleus was only a couple of kilometers across at best, so it would have suffered under the Sun’s heat more than a bigger comet would have. We’ll learn a lot from this event, there’s lots of science afoot here. This was an amazing event! And it may be a long, long time before we see the like again.”

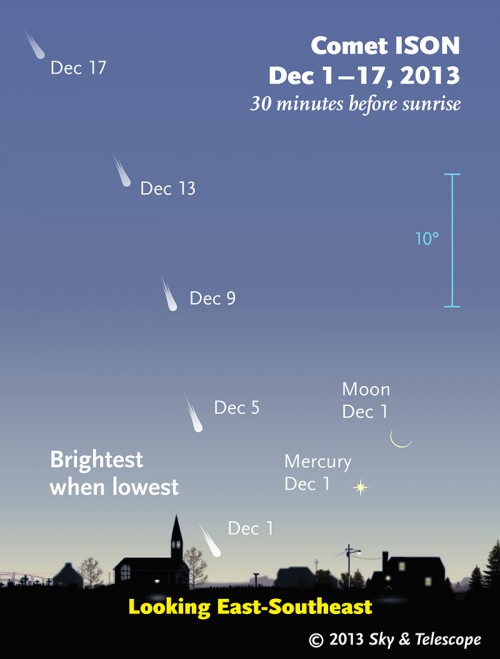

Nobody—comet experts and amateur astronomers alike—knows what to expect in the coming days; everyone will have to just wait and see. What’s left of ISON may dim to the point of not being visible at all, or it may continue to brighten and grow its tail, or what’s left of its small abused (and possibly shattered) nucleus may still fall apart and disperse completely.

“It is very possible you are seeing ISON’s trail shedding mass and emitting small particles,” said Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory comet specialist Carey Lisse in a statement to Sky & Telescope this morning. “Another, less likely possibility, is that the comet fragmented into a number of bigger pieces, like Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, and they are emitting dust. The post-perihelion dust fan we are seeing now is what you would expect from dust experiencing solar radiation pressure and gravity forces while making a U-turn around the Sun at perihelion.”

ISON will not be the “comet of the century” many had thought it might become when it was discovered over 500 million miles from the Sun last year, and, in light of ISON’s recent activity since perihelion, nobody knows yet whether or not it will even become visible to the naked eye again as it pushes back out into the Solar System. If it does become visible again, ISON will appear very low on the eastern horizon at dawn on Dec. 1, rising before the Sun higher in the sky with each passing day. Only time will tell what will come of the “ghost of ISON,” as many in the astronomy community are now calling it.

“We really hate speculating right now but if someone were to force us into an answer, we would reluctantly say that at least some faint tail remnant should be visible in the coming week or so,” adds Battams. “But this is highly speculative so please don’t take this too seriously just yet. This morning we thought it was dying, and hope was lost as it faded from sight. But like an icy phoenix, it has risen from the solar corona and – for a time at least – shines once more.”

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

This is very attention-grabbing, You’re a very professional blogger. I have joined your feed and look ahead to in the hunt for more of your excellent post. Also, I’ve shared your web site in my social networks