The history of spaceflight is full of missions that have celebrated important milestones in space during Christmas Eve—from Apollo 8’s manned flight into lunar orbit in 1968 to ESA’s Mars Express orbit insertion around the Red Planet in 2003. Yet none of these missions would have been possible were it not for NASA’s Deep Space Network, or DSN, which this year’s Christmas Eve, celebrated its 50th birthday.

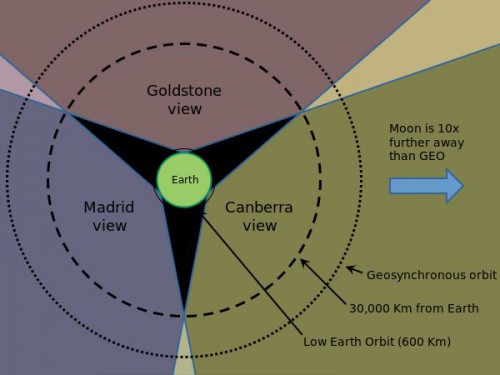

The Deep Space Network comprises a vast array of large parabolic-dish radio antennas, tracking stations, communication facilities, and data processing centers around the globe. This infrastructure, in essence, constitutes humanity’s first interplanetary wireless communication network, enabling missions throughout the Solar System to have constant, around the clock, two-way communications with Earth. The DSN’s facilities are strategically placed in three different places around the Earth, which are approximately 120 degrees apart: in Goldstone, Calif., Madrid, Spain, and Canberra, Australia. This establishment of facilities ensures that as the Earth rotates, spacecraft in deep space will always be within view of at least one DSN facility, allowing for a constant, uninterrupted communications link. Each one of the DSN facilities is comprised of one 230-foot (70-meter) antenna for communications with deep-space missions to the outer Solar System and a series of smaller 112-ft (34-meter) and 85-ft (26-meter) antennas for communications with spacecraft closer to Earth and other satellites in low-Earth orbit.

The history of the DSN goes back to the 1950s, even before NASA had come into existence on 1 October 1958. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, then under the supervision of the U.S. Department of Defense, was tasked with creating a deep-space tracking and communications network to support the mission of the first U.S. satellite Explorer 1 and the Ranger series of unmanned deep-space probes, that returned the first close-up images of the Moon’s surface. The resulting network that was created to that end, named the Deep Space Instrumentation Facility, was moved over to the jurisdiction of NASA along with JPL on 3 December 1958, mere months after the space agency was established. Fifty years ago this week, on 24 December 1963, it was officially renamed the Deep Space Network, quickly establishing itself as the sole means of communicating with any deep-space mission ever to leave Earth.

The DSN had been an integral part in many history-making events. On 14 July 1964, when Mariner 4 transmitted the first-ever close-up photographs of the surface of Mars to an awestruck crowd back on Earth, the DSN antennas where the ones to receive them. And, on 20 July 1969, the whole world could watch the human species’ single greatest achievement ever, undold live on TV, while Neil Armstrong was leaving his first footprints on the lunar soil at the Sea of Tranquility. “As a key element in all of those dramatic spacecraft events, the DSN shared their excitement, but saw a quiet, unreported drama of its own,” writes Douglas J. Mudgway in his NASA History Series book Uplink-Downlink: A History of the Nasa Deep Space Network, 1957-1997. “There were occasions when the success or failure of a multimillion dollar spacecraft, the reputation of NASA, or the recovery of critical science data from a far planet, lay in the hands of the DSN and not infrequently, those of a crew member at a distant tracking station.”

This became readily evident in April 1970, when the large DSN antennas were the only means of contact with the Apollo 13 crew, after an oxygen tank explosion had crippled their spacecraft on the way to the Moon. Unable to use the Apollo spacecraft’s high-gain antennas, the crew relied on the DSN’s ability to receive their faint transmissions and help Mission Control guide them safely back to Earth. Another less-dramatic mission recovery occurred in the 1990s, when the Jupiter-bound Galileo probe failed to fully deploy its high-gain antenna, leaving the spacecraft with only a low-gain antenna of limited bandwith, threatening to condemn the whole mission to failure. Through the utilisation of advanced signal processing techniques, the big 70-meter antennas of the DSN network were able to receive Galileo’s faint signals, turning the mission into what proved to be a spectacular success.

Indeed, every landmark robotic mission series flown by NASA—from Mariner to Viking to Voyager to Cassini—relied to the DSN network, to transmit their amazing photographs and science data from every corner of the Solar System, making hundreds of previously unknown worlds known to man. And when the Voyager 1 probe finally made its passage into interstellar space in August 2012, following a 34-year epic trek through the outer Solar System, the DSN was the one to record the momentous event. “Today, the DSN supports a fleet of more than 30 U.S. and international robotic space missions,” says DSN Project Manager Al Bhanji of NASA’s JPL.”Without the DSN, we would never have been able to undertake voyages to Mercury and Venus, visit asteroids and comets, we’d never have seen the stunning images of robots on Mars, or close-up views of the majestic rings of Saturn.”

But NASA and the U.S. space program haven’t been the only beneficiaries of the Deep Space Network. Almost every other deep-space mission flown by the European and Russian Space Agencies, have heavily relied on the DSN for telemetry and communications link support throughout the network’s 50-year history. India’s Mars Orbiter Mission that launched in November 2013 currently on its way to Mars, is the latest addition to the list.

Planetary mission support aside, the DSN is a regular contributor to Earth-bound radio astronomy observations as well, through the use of Very Long Baseline Interferometry, or VLBI. This technique allows for arrays of different radio antennas that are very far apart to be used as a single bigger antenna, with a size equal to that of the distance that separates them. This way the DSN can be used for probing quasars and other active galactic nuclei that are located billions of light-years away. The DSN also regularly contributes to planetary science by tracking the trajectories of Near Earth Asteroids, or NEOs, which are objects whose orbits bring them in proximity with the Earth. The large 70-meter antennas of the DSN network can map NEOs in high precision and help calculate their future trajectories.

With the recent successful deep-space optical communications demonstration carried by NASA’s LADEE spacecraft from lunar orbit, it is hoped that the DSN network could be upgraded to implement this new communications technology. This could enable future interplanetary spacecraft to achieve transmission rates that were previously undreamed of, making interplanetary high-definition 3-D video broadcasts a reality. “In 2063, when we celebrate the Deep Space Network’s 100th anniversary,” says Bhanji, “we can imagine that we might be recalling the amazing days when our antennas streamed high-res video as the first humans stepped onto the surface of Mars. Or that day when we discovered a new living ‘Earth’ orbiting a distant star.”

It is unclear if and when such a future day will come to pass. But if it does, NASA’s Deep Space Network will have been the enabling factor, just as it has been for every other single interplanetary mission throughout the history of spaceflight.

Video Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

A very thoughtful, interesting article on a most significant aspect of spaceflight. DSN was a logical step in cosmic communications, surpassing the yeoman efforts of Sir Bernard Lovell’s Jodrell Bank and other trackers around the globe. As we move to ever-sophisticated planetary vehicles, upgrades to the DSN are required. It’s a “no- brainier.” What humanity will be able to see, hear and experience in another 50 years boggles the imagination. Let’s again hope we muster the forces to make the exciting discoveries yet to come a reality.