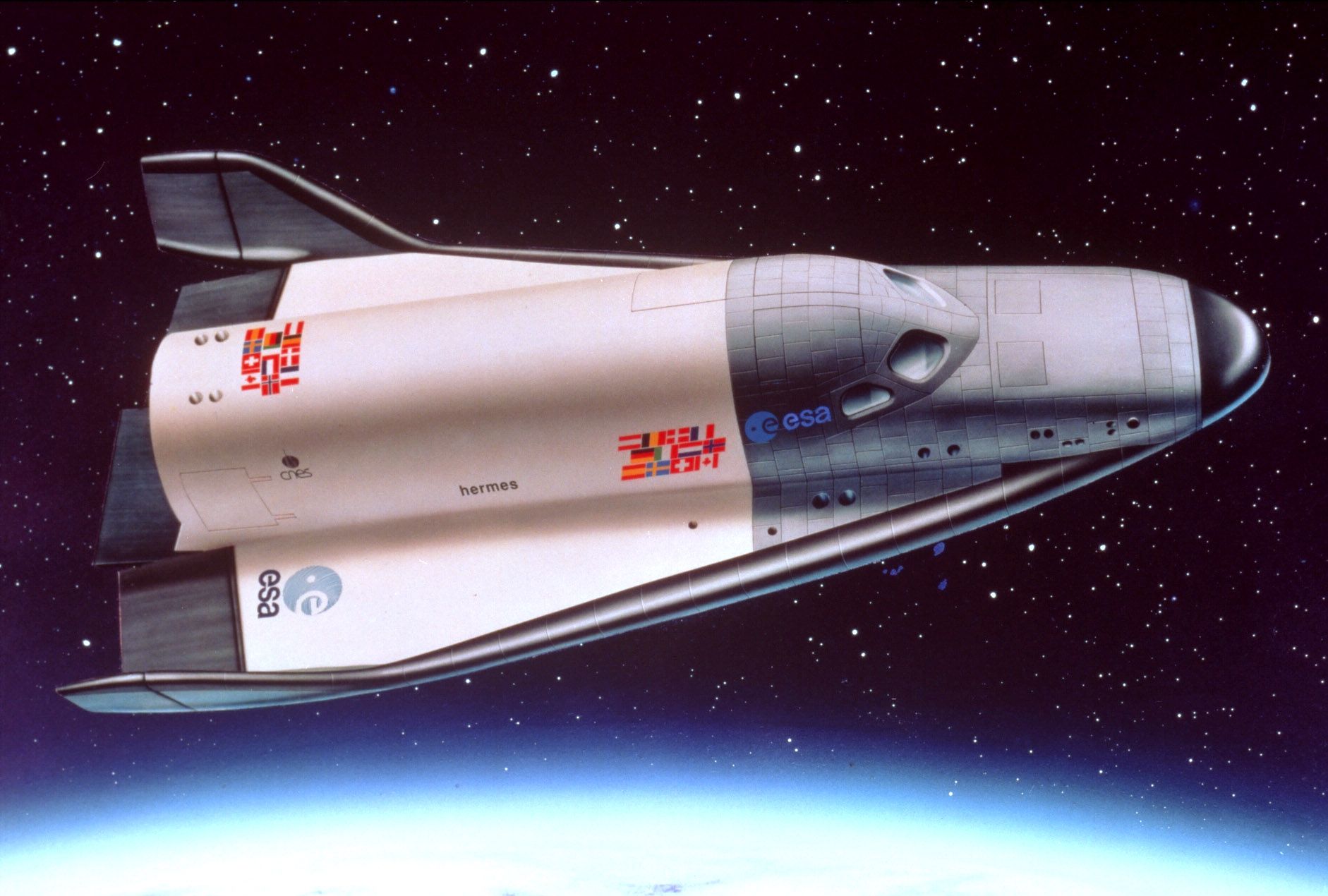

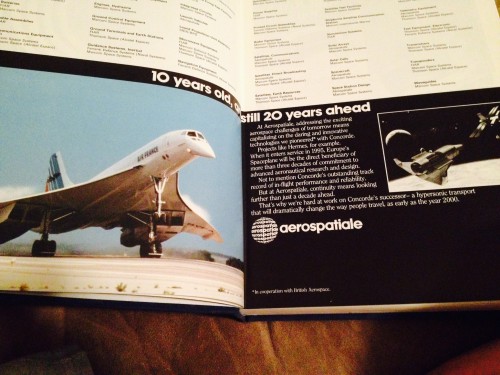

The prose in the 1986 Aerospatiale advertisement was breathless: “10 years old, and still 20 years ahead,” it started. The ad continued, “At Aerospatiale, addressing the exciting aerospace challenges of tomorrow means capitalizing on the daring and innovative technologies we pioneered [in cooperation with British Aerospace] with Concorde … Projects like Hermes, for example.” Next to this hopeful paragraph, a full-color photo showed the supersonic passenger plane Concorde landing, a nod to France’s aviation prowess. The more intriguing image, however, lay to the right: Europe’s spaceplane, Hermes, is seen rendezvousing with a space station in low-Earth orbit. What happened to the future that wasn’t—Europe’s Hermes spaceplane?

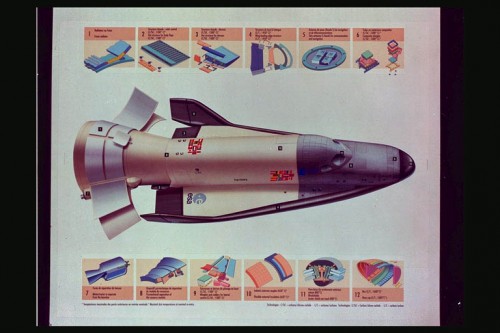

The genesis for Hermes, meant to be Europe’s answer to the United States’ Space Transportation System (or more commonly known as the space shuttle), began in the early 1980s with France’s space agency, CNES. It was proposed that Hermes, described in Jane’s Spaceflight Directory 1986 (where the Aerospatiale advertisement was found) as being “about half the size of the US Shuttle,” would launch into space on an Ariane 5 rocket and land on Earth like a plane. Jane’s also stated that development was to begin in 1988, with a launch to happen in 1997. More optimistically, the Aerospatiale advertisement previously referenced stated Hermes would “enter service in 1995.”

Hermes was meant to provide functions such as transferring crew, equipment, and payloads, also similar to the U.S. shuttle. It was meant to meet up with manned space stations such as the U.S. Space Station Freedom, which was also being developed at that time and would ultimately transition into becoming what we know now as the International Space Station (ISS).

Jane’s stated: “Mission duration with 4-6 crew would be 8 days, but this could be extended to 30 days with a smaller crew. Hermes could be docked to a space station for 90 days.” The spaceplane was to be launched from Kourou, and landing could take place at sites in Europe and Kourou. Aerospatiale and Dassault-Breguet were to be responsible for designing the spacecraft.

However, it soon appeared that Hermes would go the way of the United Kingdom’s HOTOL and the then-Soviet Union’s Buran spaceplanes (both canceled projects). The first blow happened not in Europe, but in Florida.

The United States’ Space Shuttle Program sustained a huge loss with its January 1986 Challenger tragedy. As a result, added safety considerations drove up the cost of the spaceplane—and its weight. A March 5, 1987, issue of New Scientist detailed problems emerging. An article stated, “[Hermes] is now so heavy that the rocket intended to launch it into orbit would never lift [it] off the ground.” Development costs rose, and by November 1987 it was decided to continue the program under the European Space Agency (ESA).

According to the ESA, in its final incarnation Hermes was to carry three astronauts and a 3,000-kg payload. The launch weight was to be around 21,000 kg, according to the ESA (this was seen as the Ariane 5’s upper weight limit). But timelines kept slipping, first to a launch in 1998. By 1991, an unmanned test flight was envisioned to happen around 2002, with a manned mission to happen a year later. But this, too, was optimistic, and by 1992 rising costs and delays killed Europe’s spaceplane. With the exception of a few models, the spaceplane never left the drawing board.

Hermes’ legacy is apparent in a couple of current projects. ESA’s IXV Intermediate eXperimental Vehicle is intended to be launched on a Vega rocket later this year and is meant to have the maneuvering abilities upon reentry similar to the space shuttle. In addition, the ESA announced in January that it intends to have some involvement in Sierra Nevada Corporation’s Dream Chaser project.

Hermes lives on, not as a flown artifact of a past age of spaceflight, but as a monument—resplendent in glass and steel—at the Euro Space Center near Redu in Belgium. It may be a tribute to a future that didn’t happen, but its resonances are still felt.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

What an interesting and eccentric chapter in (almost) spaceflight history — thanks!

Fascinating — and by the Many Worlds Interpretation, there are worlds where it came to be, and those worlds are just as real as this one.