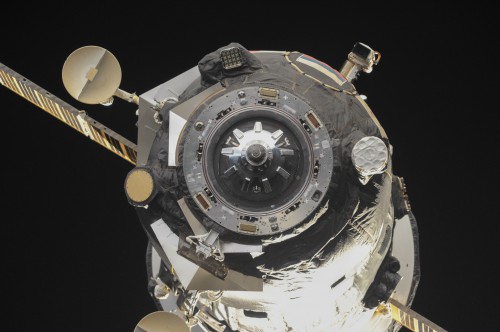

Less than six hours after departing Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, Russia’s Progress M-24M cargo craft successfully docked automatically at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the International Space Station’s (ISS) Pirs module at 11:31 p.m. EDT Wednesday. The spacecraft brought approximately 5,500 pounds (2,500 kg) of equipment, supplies, and experiments to the station’s incumbent Expedition 40 crew—which consists of Russian cosmonauts Aleksandr Skvortsov, Oleg Artemyev, and Maksim Surayev, U.S. astronaut Reid Wiseman, and Germany’s Alexander Gerst, under the command of U.S. astronaut Steve Swanson—and will remain in place through late October. At the time of docking, the ISS and Progress M-24M were orbiting about 259 miles (418 km) over the Pacific Ocean, just off the western coast of South America.

Yesterday’s successful docking marks the third Russian Progress to visit the space station in 2014, following the missions of Progress M-22M in February-April and Progress M-23M in April-July. The spacecraft was rolled out to Site 1/5 at Baikonur, encapsulated within the payload shroud of its mammoth Soyuz-U booster, early Tuesday, ahead of its scheduled liftoff at 3:44 a.m. local time Thursday (5:44 p.m. EDT Wednesday). As described in AmericaSpace’s Progress M-24M preview article, the visiting vehicle delivered food, maintenance hardware for the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS), personal crew items, and general supplies. Experiments included a habitat which can house up to 25 snails, forming part of the “Regeneration-1” investigation to examine morphological and physiological changes during prolonged exposure to the strange microgravity environment.

In the final hours before yesterday’s launch, the process of loading liquid oxygen and rocket-grade kerosene (known as “RP-1”) aboard the Soyuz-U got underway and, upon completion, transitioned to a “topping” mode, whereby all cryogenic boil-off propellants were rapidly replenished until close to the launch time. This ensured that the liquid oxygen tanks were maintained at Flight Ready levels, ahead of the ignition of the Soyuz-U’s single RD-118 first stage engine and the RD-117 engines of the rocket’s four tapering strap-on boosters. Internal avionics were initiated, and the on-board flight recorders were spooled-up to monitor the vehicle’s systems throughout ascent to orbit.

At T-10 seconds, the turbopumps on the core and strap-on boosters came to life. Following confirmation that the engines are all burning at full power, the fueling tower was retracted and Progress M-24M roared into the darkened Baikonur sky at exactly 3:44 a.m. local time Thursday (5:44 p.m. EDT Wednesday), turning night into day across the desolate Kazakh steppe. Rising rapidly, the vehicle exceeded 1,100 mph (1,770 km/h) within a minute of liftoff, during which time the maximum amount of aerodynamic stress (known as “Max Q”) impacted its airframe. At T+118 seconds, at an altitude of about 28 miles (45 km), the four strap-on boosters exhausted their supply of liquid oxygen and RP-1 and were jettisoned, leaving the central core and its single engine to continue the “second stage” phase of the ascent towards orbit.

By two minutes into the flight, the rocket was traveling at over 3,350 mph (5,390 km/h). The payload shroud and escape tower were discarded shortly afterward, at 3:46:45 a.m. Baikonur time Thursday (5:46:45 p.m. EDT Wednesday), and, some four minutes and 50 seconds after leaving the Kazakh steppe, the core stage duly separated at an altitude of 105 miles (170 km). At this point, the RD-0110 engine of the third stage ignited to boost Progress M-24M to a velocity in excess of 13,420 mph (21,600 km/h). By the point of third stage separation, about eight minutes and 45 seconds into the flight, the vehicle was in space. Fifteen seconds later, at 3:53:00 a.m. Baikonur time Thursday (5:53:00 p.m. EDT Wednesday), exactly nine minutes after liftoff, Progress M-24M separated from the third stage and entered free flight in a target orbit of approximately 120 x 152 miles (193 x 245 km), inclined 51.6 degrees to the equator. Within 20 seconds, its electricity-generating solar arrays and Kurs (“Course”) rendezvous and navigation hardware had been deployed.

Following a well-trodden “fast rendezvous” profile, first trialed in August 2012, it was anticipated that Progress M-24M would dock automatically at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the station’s Pirs module at 9:30 a.m. Baikonur time Thursday (11:30 p.m. EDT Wednesday). As circumstances transpired, physical docking occurred just 60 seconds later than intended, at 9:31 a.m. Baikonur time Thursday (11:31 p.m. EDT Wednesday), completing a flight of just five hours and 47 minutes.

To put this into context, five previous Progresses have successfully executed fast-rendezvous profiles since August 2012, and the current record is held by Progress M-20M, which reached the ISS in just five hours and 41 minutes, back in July 2013. In second place is Progress M-16M, which achieved a docking after five hours and 43 minutes in the inaugural use of the fast-rendezvous system in August 2012, with yesterday’s Progress M-24M now establishing itself in third place. In terms of the five piloted Soyuz spacecraft which have followed the minimum-duration rendezvous profile since March 2013, the current record is held by the crew of Soyuz TMA-09M, who docked at the ISS just five hours and 39 minutes after their launch in May 2013.

In order to prepare for the arrival of their unpiloted Russian visitor, the Expedition 40 crew began their Wednesday work day somewhat later than normal, at 6:00 a.m. EDT. A NASA news update reported that Skvortsov, Artemyev, and Surayev took a four-hour nap, beginning at 12:30 p.m. EDT, to ensure that they were properly rested for the late-night rendezvous and docking. Progress M-24M will remain attached to the station until the fall, with undocking and departure presently anticipated on 27 October.

The Progress program has a storied history. Its development began in 1973 in response to the anticipated problem of resupplying and refueling the Soviet Union’s Salyut 6 space station, whose cosmonauts went on to spend more than six months at a time in orbit. Modeled closely on the Soyuz spacecraft, its interior was redesigned to house foodstuffs, water, experiments, and fuel for the station’s maneuvering thrusters. Since its maiden voyage, Progress has seen many changes, but its role has remained largely unchanged … and the numbers speak for themselves. Between its first launch in January 1978 and tomorrow’s flight, no fewer than 145 Progresses have roared aloft. Only one has failed to reach its destination: the unlucky Progress M-12M in August 2011, whose launch vehicle suffered an engine malfunction and re-entered the atmosphere over the Altai region.

Writing in 1998, astronaut Jerry Linenger—one of the handful of U.S. astronauts to reside aboard Russia’s Mir space station—recounted the sheer joy of receiving a shoebox full of goodies from his wife and children: “Once found, and munching on fresh apples that had also arrived in the Progress,” he described in his memoir, Off the Planet, “we individually retreated from our work and sneaked off to private sections of the space station, eager to peruse the box’s contents.” Fellow astronaut John Blaha once described similar excitement: “Once we found our packages,” he wrote, “it was like Christmas and your birthday, all rolled together, when you are five years old. We really had a lot of fun reading mail, laughing, opening presents, eating fresh tomatoes and cheese.” In more recent times, ISS crew members have done much the same. In February 2008, Peggy Whitson, commander of Expedition 16, remembered crewmate Dan Tani calling one Progress “the onion express,” as the latest delivery of letters from home and fresh foodstuffs arrived.

In their book Soyuz: A Universal Spacecraft, David Shayler and the late Rex Hall speculated that the term “Progress” may have originated from the implication of having made significant progress in space station operations, although the precise heritage of the name remains unclear. What is clear, though, is that aside from the technical and functional role of Progress over the decades, it has provided an indispensable psychological crutch for dozens of cosmonauts and astronauts—a crutch which has enabled them to overcome the profound isolation of the strange microgravity environment, far from family and friends.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Wow, nice picture.

The Progress re supply program is a significant contribution to manned spaceflight as far as Earth orbital space station operations are concerned. There are obvious technical as well as psychological benefits as outlined in the article. One wonders what the apparent lack of such re supply activities during a potential 3-year round trip to Mars with eating 3-year old food and no “packages from home” could have on the crew. No doubt technology must evolve to make such a journey within reasonable human limits. Just wondering.

Don’t MRE’s have a 5-year lifespan?