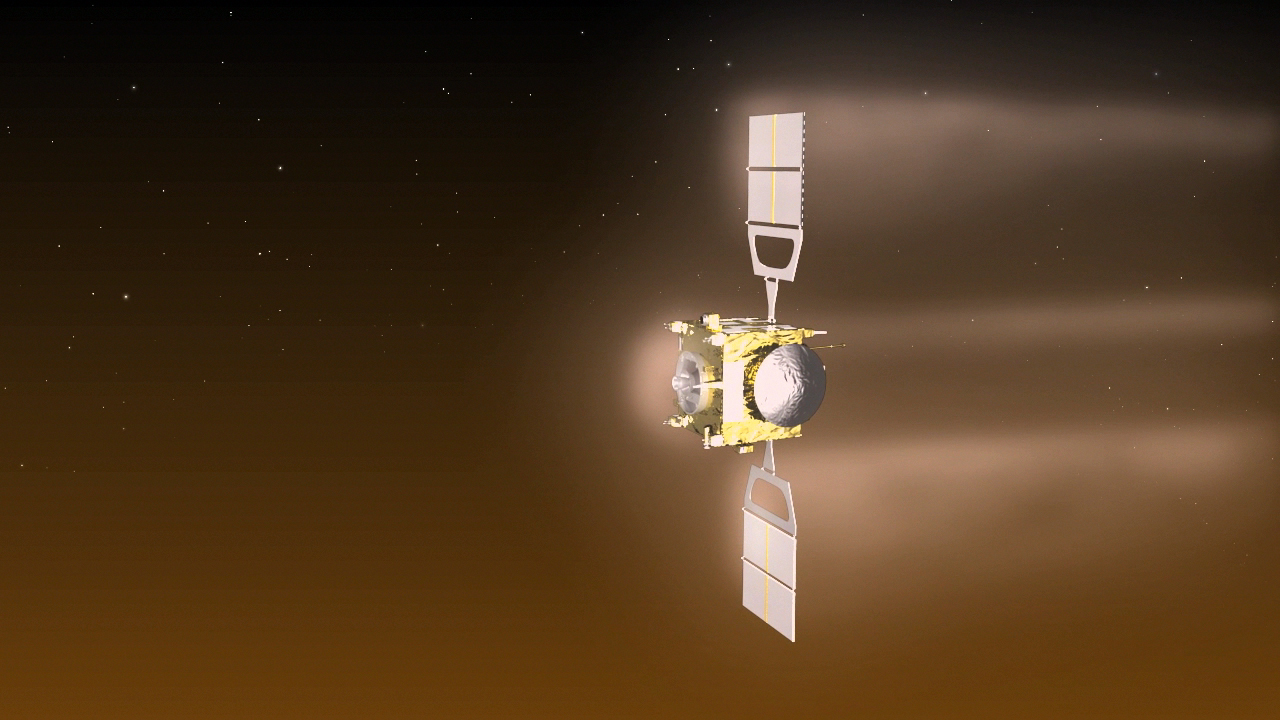

Following the conclusion of an exciting, as well as risky, aerobraking campaign which allowed it to skim in and out of Venus’ dense atmosphere, the European Space Agency’s Venus Express spacecraft has successfully raised its orbit once again, so as to continue its normal science observations until its expected end of operations later this year.

Based on the design of the equally successful Mars Express spacecraft, which has been exploring the Red Planet for more than a decade, Venus Express was ESA’s first robotic ambassador to Earth’s “twisted sister,” which it studied extensively for the past eight years after arriving there in April 2006. With its fuel now running low and having already performed well beyond the initial expectations of mission planners, the intrepid robotic explorer was given a final assignment earlier this year: to glide through the upper layers of the Venusian atmosphere as part of a daring and experimental aerobraking campaign.

Similar to the way a sailing boat uses the wind for navigation, interplanetary spacecraft can use the drag of a planet’s atmosphere in order to decrease their speed and be captured by the planet’s gravitational field, thus negating the need for carrying large amounts of propellant for course correction maneuvers. In addition, aerobraking can be used by orbiting spacecraft for lowering their altitude and changing the eccentricity of their orbits from highly elliptical to more circular ones. Yet, even though as a course correction technique aerobraking is very effective, it is also a risky and challenging one. While the spacecraft skims through the upper layers of the atmosphere at very high speeds during this process, all of its kinetic energy gets converted into heat, forcing it to experience very high temperatures and dynamic pressures which require the use of adequate shielding.

In the case of Venus Express, which was only designed for orbital operations, mission planners were uncertain whether the spacecraft would survive this daring surfing in and out of the Venusian atmosphere. Despite its inherent risk, the aerobraking campaign was of high value to mission planners, giving them the chance to gain invaluable experience in low-altitude spaceflight operations that could be used in future interplanetary missions. In addition to its benefits to future missions, aerobraking could allow scientists to probe parts of the Venusian atmosphere that weren’t otherwise accessible, thus adding to the mission’s overall science return. To that end, the mission’s team initiated the aerobraking campaign by conducting a so-called “walk-in” phase right after the end of normal science operations in 18 May, which lasted until early June. During that time, ground controllers at the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, commanded Venus Express to prepare for its new role as a dare-devil, while letting the spacecraft gradually decline the perigee of its highly elliptical 24-hour period, 66,000 by 250 km orbit, down to 136 km.

Following the beginning of the main aerobraking phase a month later, Venus Express began to experience significant atmospheric drag as well as steep increases in temperature and dynamic pressures during its daily 100-second duration passages through the upper layers of the atmosphere, at speeds of 10 km/s or 36,000 km/h. The solar panels, in particular, being one of the most sensitive parts of the spacecraft, were exposed to sudden temperature swings of more than 100 degrees Celsius, from a low -150 up to 15 degrees. Despite these high structural stresses, Venus Express performed flawlessly without displaying any signs of degradation whatsoever, even after it had achieved its lowest altitude ever of 129.1 km near the end of the aerobraking campaign. “The spacecraft has proven to be very robust and has apparently experienced no substantial degradation in any area, but a detailed evaluation is still to take place,” says Joerg Fischer, mission operations engineer for Venus Express.

Even though the orientation of the spacecraft during the aerobraking maneuver was such that precluded the use of most of its science instruments, the mission’s team was nevertheless able to operate the onboard Magnetometer and the Analyzer of Space Plasmas and Energetic Atoms, or ASPERA-4, which measures atmospheric ion and particle abundances. During these limited science observations, scientists were able to make in-situ measurements of the upper Venusian atmosphere from such low altitudes for the first time. “We have explored uncharted territory, diving deeper into the atmosphere than ever before,” says Håkan Svedhem, ESA Project Scientist for Venus Express. “We’ve measured the effects of atmospheric drag on the spacecraft, which will teach us how the density of the atmosphere varies on local and global scales.” These data may ultimately help answer many standing questions about the evolution of Venus and the processes that govern the slow loss of its atmosphere into space. “Until now, we’ve been focusing mainly on the lower atmosphere above and below the clouds, and aerobraking takes us at the very top end of the atmosphere, where it reaches space,” said Colin Wilson, science operations coordinator for Venus Express, during an ESA Hangout that took place on 10 July. “And this is really interesting, because this is where atmospheric escape happens, where the constituents of the atmosphere are lost into space … By understanding density variations and so on at the edge of the atmosphere, we can try to understand how [atmospheric loss] happens.” Besides its scientific benefits, the Venus Express aerobraking campaign provided ground teams with important knowledge regarding the challenges of conducting such low-altitude operations. The mastering of this technique could prove very useful for ESA’s mission planners in the future. “We have already gained valuable experience in operating a spacecraft in these challenging conditions that will be important for future missions that may require it,” says Patrick Martin, Venus Express mission manager at the European Space Astronomy Centre, in Madrid, Spain.

Having successfully completed its aerobraking campaign on 11 July, Venus Express executed a series of 15 orbit correction maneuvers for the remainder of the month while utilising the last of its fuel reserves, in order to raise its perigee from 130 km up to 460 km. The spacecraft’s new 63,000 km by 460 km orbit will allow it to resume normal science operations until approximately mid-December, when natural orbital decay will eventually cause it to make a final death plunge into the infernal Venusian atmosphere, putting an end to a triumphant mission. In the meantime, scientists will be busy analysing the mission’s data treasure trove, which will provide new insights into the history and evolution of Earth’s “twin sister” in the process. “We are delighted with the success of the experimental aerobraking campaign, and are looking forward to assessing the details over the coming months,” says Martin. “Meanwhile, we are enjoying the view from our new orbit around Venus, and plan to continue augmenting the scientific return of this exciting mission.”

Besides its tremendous scientific return, perhaps the most important result of the Venus Express mission will be the realisation that far from being an uninteresting, hellish world, our neighboring planet is full of tantalising and exciting mysteries, just waiting to be uncovered and explored.

Video Credit: ESA

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Navigating a spacecraft through the atmosphere of Venus, or driving a robotic science laboratory across the Martian landscape, if that doesn’t inspire a young person to pursue a career in math, physics, engineering, etc., then we are doomed to a future of twerking and tweeting. Excellent update Leonidas, our “go to for the info” guy!

Once again, Leonidas has provided readers with a thorough, comprehensive and analytical article. It would be an understatement for me to say that I look forward to each and every posting. AmericaSpace readers are indeed fortunate!