On this day in 1990, shuttle Discovery and five astronauts rocketed higher above the Home Planet than any humans since the end of the Apollo lunar landing era. By the time STS-31 Commander Loren Shriver, Pilot Charlie Bolden and Mission Specialists Steve Hawley, Kathy Sullivan and Bruce McCandless settled into orbit, they were soaring at an altitude of 380 miles (610 kilometers) and for the first time since Apollo it was possible to see the curvature of Earth and glimpse its true nature as a “real” planet.

And the singular reason for that extreme altitude was STS-31’s primary payload: the 43-foot-long (13-meter) Hubble Space Telescope (HST), once described by NASA Administrator James Beggs as the world’s eighth wonder, an astronomical powerhouse that would observe the Universe in unrivalled depth. But getting the huge Hubble into orbit posed a pair of conflicting problems: it had to be lofted as high as possible, above the sensible atmosphere, to allow it to scrutinize the cosmos, but needed to operate in a low enough orbit for the shuttle and its finite propellant supply to reasonably reach.

In fact, “reaching” Hubble was a matter not just for Shriver & Co., for the telescope had long been planned to be revisited by successive shuttle crews over perhaps 15 years or more for routine servicing, upgrades and the replacement of scientific instruments. “It’s a big vehicle, with a lot of cross section,” remembered Sullivan. “You need to get it into a very low-density region, very high.

“Its control systems…are wimpy, in a sense,” she added. “Magnetic torquers and control moment gyros are not high-impulse things, so you want to get it pretty high, so that the pointing systems can keep it still for long observations.”

In the months prior to the loss of Challenger, Hubble was slated to fly in October 1986. But after a decade in development and a multitude of troubles with contractors, it had fallen 30 percent over-budget and months behind schedule.

Challenger’s traumatic destruction in January 1986 and the grounding of the shuttle fleet for nearly three years, perversely, afforded the Hubble team some breathing room to complete a major thermal vacuum test, add more powerful solar arrays, enhance redundancy of critical systems, improve flight software and add better connectors. Failure-prone nickel-cadmium batteries were replaced with more capable nickel-hydrogen ones.

Crew members were assigned in 1985, but the original commander, John Young, was pulled in the post-Challenger down time and replaced by Shriver, who joined the rest of the original crew in March 1988, tracking a revised launch date of June 1989. But with several “infrastructure-critical” missions ahead in the pecking order—including two Tracking and Data Relay Satellites (TDRS), the Magellan and Galileo planetary probes and a number of classified payloads for the Department of Defense—STS-31 found itself shifted to the rear of the queue when shuttle operations resumed in September 1988.

Eventually, the mission found itself anchored to March-April 1990, which carried its own problems. “The year 1990 was close to a solar maximum year,” remembered Sullivan, “so the envelope of the atmosphere is physically larger.”

The effect was that Hubble had been inserted into a higher orbit, which by mid-1989 had been determined at about 380 miles (610 kilometers). To get this high demanded a long-duration “burn” of Discovery’s Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines, lasting over five minutes. And that meant that 50 percent of STS-31’s available propellant would be expended just getting to its desired altitude.

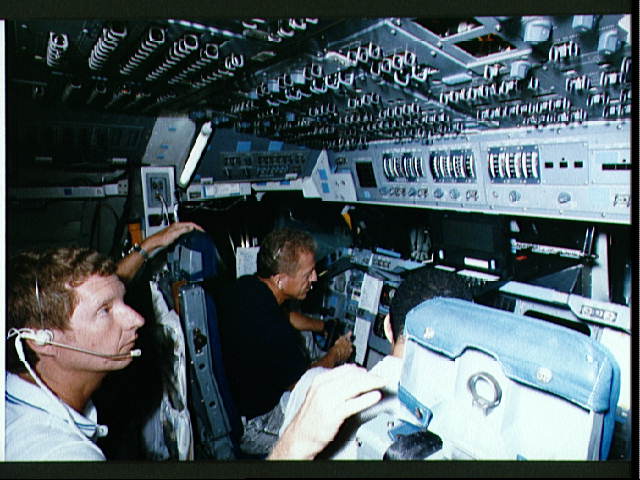

The mission parameters were complicated still further by the need for enough remaining propellant to re-rendezvous with Hubble, if needed, in the event of a malfunction after deployment and enough to redeploy it again and enough to perform another separation burn and enough to conduct another long-duration OMS firing to return safely to Earth. With such monstrously tight fuel margins, Shriver’s crew trained exhaustively on their collective response to propellant alarms in the cockpit.

On “ordinary” shuttle flights, the first prudent step after a propellant alarm would be to check if it was a false alarm. STS-31 had no such luxury: the crew would have to assume that it was a real leak and either lower their orbit or return immediately to Earth.

In spite of the hazards, the mission was eagerly anticipated by the astronomical community. For Hubble and its five scientific instruments—the Wide-Field/Planetary Camera (WF/PC), Faint Object Camera (FOC), High Resolution Spectrograph (HRS), Faint Object Spectrograph (FOS) and High Speed Photometer (HSP)—would facilitate observations far deeper and much “earlier” into the Universe than ever before.

STS-31’s opening launch attempt on 10 April 1990 ran smoothly. The countdown ticked away to T-4 minutes when abnormal pressures and turbine speeds in one of the Auxiliary Power Units (APUs) forced a scrub.

The troublesome APU was replaced and a revised launch attempt was set for 24 April. Again, the five astronauts boarded Discovery and sat through a lengthy countdown.

As McCandless performed his standard communications checks with Mission Control, he could not resist pointing to Florida’s favorable weather. “Looks like a nice day down here,” he radioed Capcom Steve Oswald.

“That’s good,” replied Oswald, keenly aware that weather also needed to be good at STS-31’s Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) sites. “We’re working on other places.”

The countdown continued down to T-31 seconds, at which point the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS) prepared to hand off control to the shuttle’s on-board computers. Another hold was called, agonizingly, when software failed to shut down the liquid oxygen outboard fill-and-drain valves on the Ground Support Equipment (GSE).

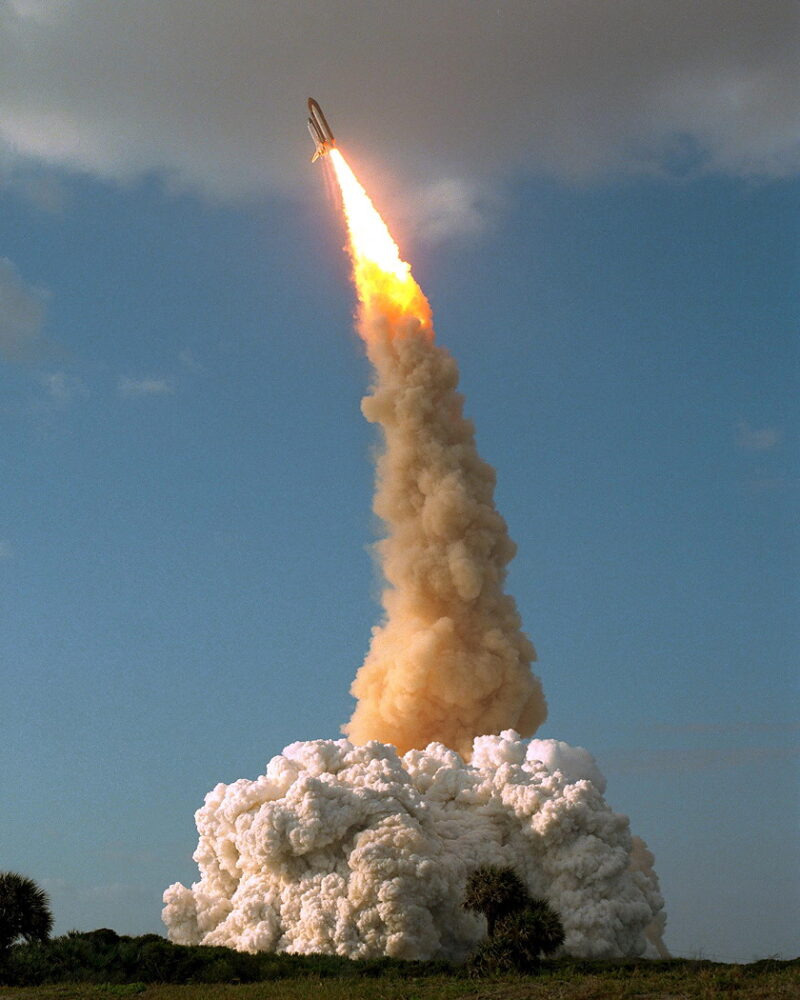

In astonishingly short order, the glitch was corrected and Discovery sprang from Earth a few minutes later than intended at 8:33 a.m. EDT. “Our window on the Universe,” came the launch announcer’s exuberant call as Discovery speared into space, executing a dramatic “roll program” maneuver seconds after liftoff.

Less than nine minutes later, Shriver, Bolden, McCandless, Hawley and Sullivan slipped smoothly into the highest orbit yet reached by a shuttle crew. And the view of Earth for five astronauts who had flown no higher than 240 miles (390 kilometers) on their previous missions proved nothing short of spectacular.

Flying higher than anyone since Apollo 17, the Home Planet’s curvature and its true nature as a planet was obvious. “It was truly noticeable and impressive on board,” Hawley told the post-mission press conference.

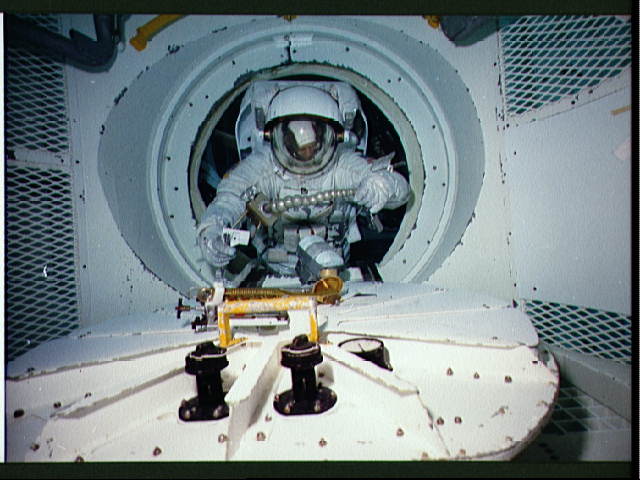

But there was much to do. Beyond Discovery’s aft flight deck windows, in the floodlit payload bay, sat Hubble, its silver insulation glittering in the stark orbital sunlight.

Its deployment on 25 April 1990, a day after launch, would demand intricately close co-ordination with Mission Control. And as circumstances would transpire, not everything ran according to plan.

The second part of this story will appear tomorrow.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:“Somebody Get a Camera”: Remembering the Deployment of Hubble, OTD in 1990 - AmericaSpace

Pingback:“Somebody Get a Camera”: Remembering the Deployment of Hubble, OTD in 1990 - SPACERFIT